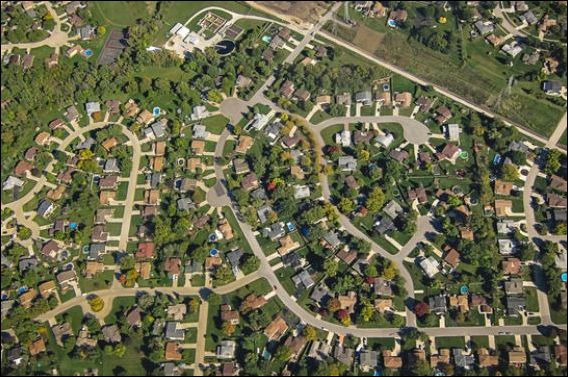

“Suburbs regain their appeal!” shouts a headline for an article in the Wall Street Journal today accompanied by a quarter-page aerial photograph (shown above) of a cul-de-sac subdivision in Chicago. The editor’s treatment of the story, which is based upon research findings by Brookings Institution scholar William H. Frey, is highly misleading. While the article does say that population growth in major cities declined slightly between 2012 and 2013 and population growth in the suburbs rebounded incrementally, the differences are small and the larger narrative — that urban core jurisdictions are gaining, not losing population, while suburban growth remains subdued — still holds true.

Indeed, the article quotes Frey as saying that it remains unclear “whether the city slowdown signals a return to renewed suburban growth.”

The issue is important because it bears upon the debate over the future of metropolitan development. Urbanists, who support more compact, walkable, mixed-use development, have cited the changing growth patterns since the 2007-2008 recession as evidence of a fundamental shift in the kinds of communities people want to live in. The suburbanists argue that the trend is temporary and that pre-recessionary growth patterns will reassert themselves. The headline and photo suggest that urbanism is losing momentum. In fact, the article provides no such evidence at all.

Indeed, the article touches not at all upon a trend that renders suspect any analysis based upon comparisons between population growth in “urban core,” “suburban” and “exurban” jurisdictions. That trend is densification and re-development. Some unknown percentage of “suburban” growth can be attributed to re-development initiatives occurring in places such as Tysons, in Fairfax County. That so-called “suburban” jurisdiction is fostering higher-density, transit-oriented development around five soon-to-open Metro stations. In effect, the dense, mixed-use land use patterns typical of the urban core, in Washington, D.C., are transforming the “suburbs.”

By proclaiming that “suburbs regain their appeal” and displaying a photograph of a low-density, cul de sac subdivision outside of Chicago, the headline suggests that the pattern of metropolitan growth that prevailed between 1945 and 2007, commonly called “suburban sprawl,” has reasserted itself. That’s just plain wrong.

In all likelihood, the population rebound of urban core jurisdictions will slow from its recent boom. The reason will not be due to changing consumer demand for walkable urbanism, which is running unabated, but the inherent difficulty increasing housing supply, especially in the most desirable urban neighborhoods where NIMBYs thwart proposals to build at higher density. The constraint on population growth in the urban core is one of insufficient housing supply, not insufficient demand.

Also, in all likelihood, population will continue moving into the so-called “inner suburbs,” especially those that support re-development of aging commercial districts into walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods — sometimes supported by heavy or light rail, sometimes not. Thus, a county like Fairfax, which is mostly built out, will continue to see in-migration and population growth. But that growth won’t consist of single-family dwellings in subdivisions. Most of it will be apartments, condos and townhouses.

Bacon’s bottom line: Measuring population growth in jurisdictions defined as “urban core,” “suburban” and “exurban” doesn’t tell us much at all about what is happening in America’s major metropolitan regions. The spread of walkable, mixed-use development into so-called “suburban” counties makes a hash of the traditional categories we use to analyze population trends.