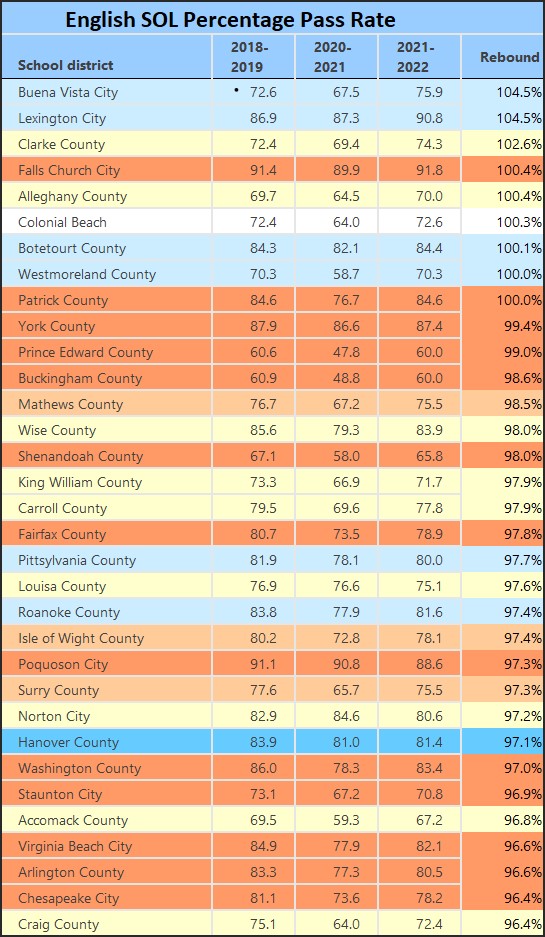

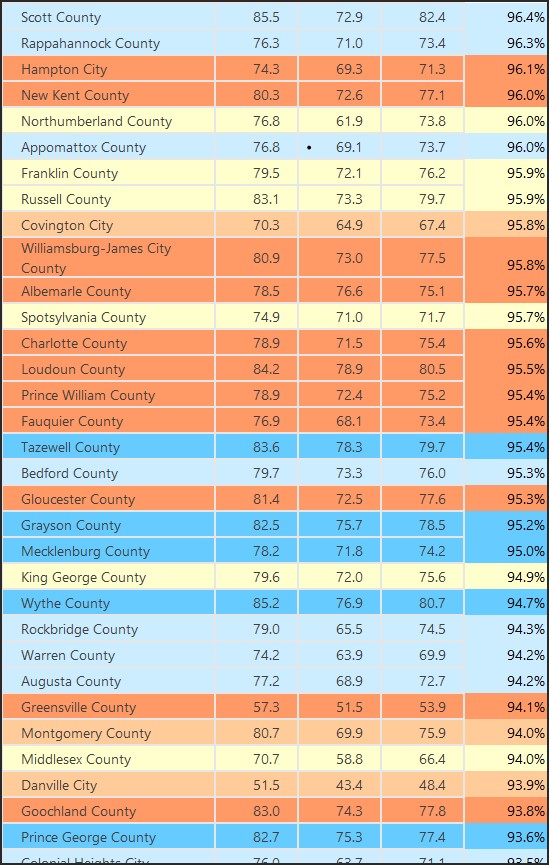

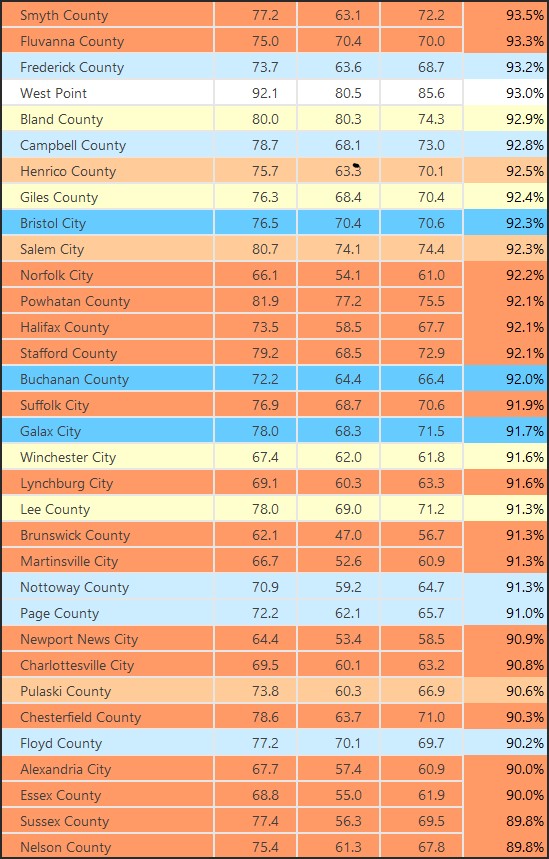

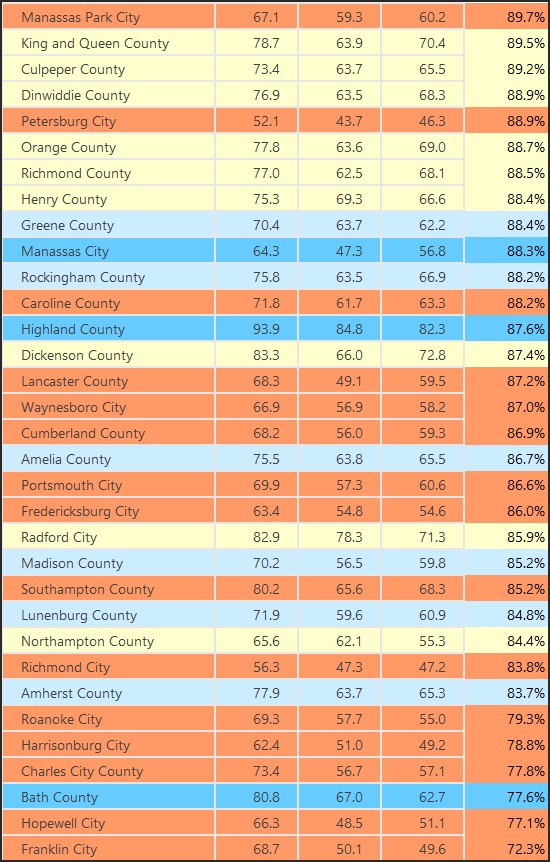

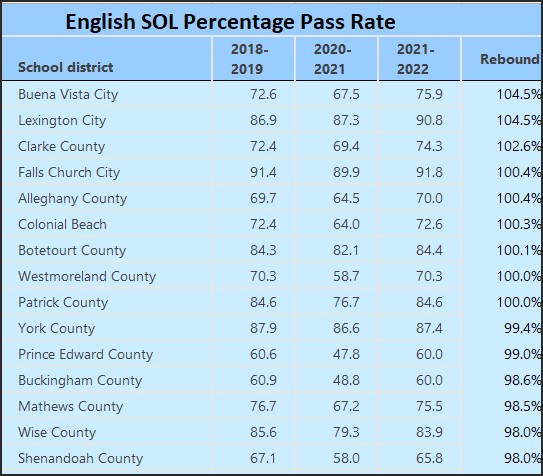

The “rebound” percentage expresses the 2021-22 English SOL pass rates to the pre-pandemic 2018-19 pass rates.

by James A. Bacon

Statewide student performance in the Standards of Learning (SOL) exams regained some ground lost earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, according to recently published Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) data. But not all school districts were equally resilient.

In 2018-19, the year before the disruptive pandemic, 77.6% of Virginia public school students passed their English SOL exams. The state did not administer the exams the next year when all schools shut down in the spring in response to the COVID panic. Then in the second academic year of the plague, when many schools had turned to remote and hybrid learning, the pass rate fell to 69.3%. This past year in which in-person learning resumed, 2021-22, the statewide pass rate rebounded partially to 73.1%.

The state averages conceal considerable variability, however. In crunching the latest VDOE numbers, Bacon’s Rebellion has identified seven school districts where the pass rate exceeds pre-pandemic performance, and seven others where the pass rate remains 20% less than it was three years ago.

In the small Shenandoah Valley cities of Lexington and Buena Vista, the English SOL pass rates are 4.5% higher than before. But in the small cities in eastern Virginia, Hopewell and Franklin, the pass rate has barely budged since the previous year, stuck at 77.1% and 72.3% respectively.

Why the disparity in outcomes?

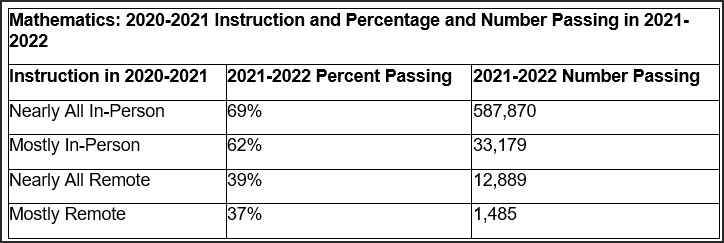

VDOE officials provided an important clue when releasing the new data last week. According to the Youngkin administration, students who engaged in in-person learning in 2020-21 scored better the following year than those who did not. Stated the press release:

A Virginia Department of Education analysis of statewide data shows a strong correlation between in-person instruction during 2020-2021 and higher achievement on the 2021-2022 SOLs. For example, 69% of students who experienced in-person instruction for nearly all of 2020-2021, and 62% of students who experienced in-person instruction for most of 2020-2021 passed their 2021-2022 math tests, compared with 39% and 37% who experienced nearly all or mostly remote instruction, respectively.

Source: Virginia Department of Education. Note: Total public school enrollment in 2021-22 was 1,251,970.

Although the pass rates for reading were higher in English reading than math, the disparity between mostly in-person and mostly remote was comparable.

That is powerful data, if it fully represents reality.

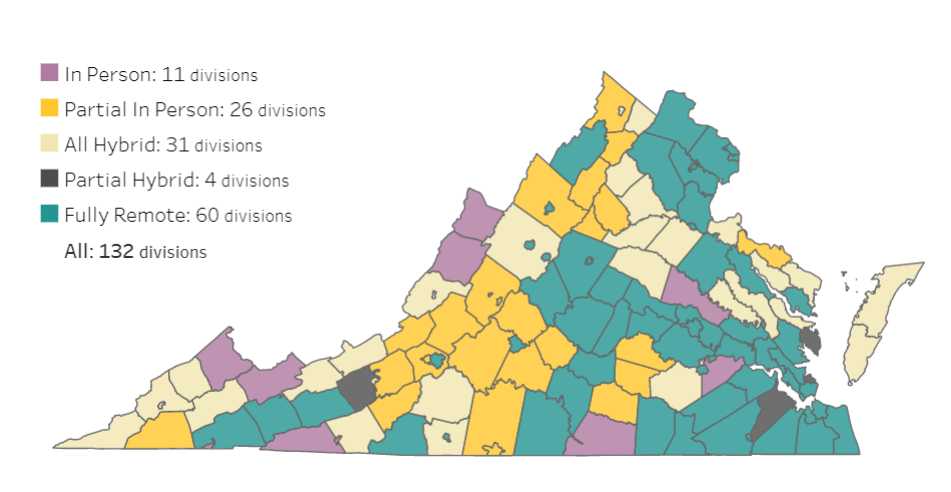

I have reservations about the data, however. It suggests that the overwhelming majority of Virginia students experienced “nearly all” in-person learning, while those engaging in “mostly remote” learning were a tiny minority. That doesn’t jive with almost everything we know about which school systems shifted to remote and which kept classrooms open. For example, here is a map showing the in-person/remote status of Virginia’s 132 school districts in August 2020.

Not only did 60 divisions embark upon the school year in fully remote mode, those districts — Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, Henrico, Chesterfield — had by far the most students. Some districts changed their mode of instruction as the year wore on, but a large majority of students undeniably started out their school year with remote learning.

For its analysis, Team Youngkin used a different methodology than those who prepared this map in 2020. According to VDOE spokesman Charles Pyle, the administration drew from the annual End-of-Year Student Record Collection, which contains a data item called “Remote Learning Percent of Time.” The analysis then divided students into the four buckets shown in the table above based on the percentage of time spent in remote learning. To reduce the possibility that mobility between districts affected the pass rates, the table includes only students enrolled in the same school for 80% or more of the year. Pyle concedes that there was some “noise” in the numbers resulting from some school districts providing estimates and some submitting precise percentages, but it’s hard to imagine that significantly impacting the overall findings.

The approach sounds reasonable. But it just doesn’t square with what everyone knows to be true: to wit, that most Virginia K-12 students were given remote or hybrid instruction in the 2020-21 school year. Indeed, Team Youngkin has argued much the same in comparing the high rate of remote learning for Virginia students compared to that for other states.

VDOE did not create district-level reports, so even if you are comfortable with its methodology, the statewide report gives us no insight into the resilience displayed by different school districts. A different approach is needed.

In the tables below, I listed the English SOL pass rate for each district in the pre-pandemic year of 2018-19 (pre-pandemic), 2020-21 (height of the pandemic when remote learning peaked), and 2021-22 (when in-person learning resumed). Next, I calculated the pass rate of the most recent year (2020-21) as a percentage of the pre-pandemic year (2018-19) to determine the degree to which SOL scores have recovered from the school shutdowns. Then I ranked the districts in the order of the rebound. Those at the top — Buena Vista and Lexington — exhibited the strongest recovery. Those at the bottom — Hopewell and Franklin — showed the least.

Finally, I categorized each district by the categories displayed in the 2020 map above. Here is the color key:

What becomes apparent from eye-balling these tables is that there is a mix at every SOL-rebound level. Some school districts that shut down in-person learning have recovered smartly. Likewise, some districts that maintained in-person learning saw significant drops in pass rates. Indeed, Bath County, traditionally one of Virginia’s strongest performers measured by SOL pass rates, lost ground in 2020-21 and then lost more ground in 2021-22.

I’m surprised by these findings. In line with what the Youngkin administration contends, I would have predicted that in-person learning in 2020-22 would have contributed to far better results the following year when students returned to school. A deeper analysis still may show that to be the case. Perhaps the difference can be attributed to the fact that the Youngkin analysis looked at math SOL scores, while I looked at English reading SOL scores, but I doubt it. Relative performance of the two are tightly correlated. I suspect that there is more to the story. Other factors are at play, and the interaction of those factors with a school district’s history of in-person/remote learning could tell us far more than remote-learning status alone.

I would have happily embraced Team Youngkin’s storyline because it comports with the narrative I have pushed on Bacon’s Rebellion. But reality is complex, darn it. I’m not suggesting that the narrative is wrong, just incomplete. There is something else going on, and we need to find out what it is.