by James Newman

No matter who you are or where you live, at some point in your day you use roads. For most people, this comes in the form of driving. Yet what happens to people who do not have a car? Since the 1950s, roads have been designed for getting private automobiles from point A (new suburban housing) to point B (jobs downtown) as quickly and efficiently as possible. Other users, such as mass transit, pedestrians, and the handicapped, were considered secondary users of this public infrastructure. Complete Streets seeks to change that. Complete Streets provides all members of the community the freedom to choose how they want to move in their community.

So, what exactly are Complete Streets? Take the inverse: An incomplete street focuses mainly on cars; has either no sidewalks or ones which are in poor condition and does not support handicapped access; has no dedicated bike or bus lanes; and finally has no pedestrian amenities such as trees, benches, and appropriate lighting. The lack of these features make a street incomplete and creates a harsh environment for those who have to get around without a car.

So, what exactly are Complete Streets? Take the inverse: An incomplete street focuses mainly on cars; has either no sidewalks or ones which are in poor condition and does not support handicapped access; has no dedicated bike or bus lanes; and finally has no pedestrian amenities such as trees, benches, and appropriate lighting. The lack of these features make a street incomplete and creates a harsh environment for those who have to get around without a car.

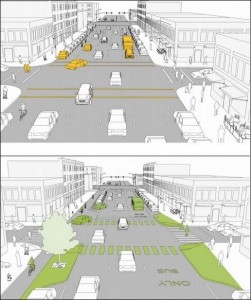

In the image above, the top picture shows an incomplete street. The bottom image shows a complete street. The complete street has trees and benches as pedestrian amenities; a dedicated bike lane protected from traffic by a physical barrier; a dedicated bus lane; and wider sidewalks with handicapped accessible curbs. Cars still have dominance over the road, but other users are given consideration. Complete Streets do NOT marginalize the car; instead they seek to legitimize other modes of travel. It is about giving the user the freedom to choose how to move around.

In writing a plan for the City of Richmond Pedestrian, Bicycle, and Trails Commission, I researched federal law; local Virginia plans from Arlington, Roanoke, and Virginia Beach; statewide plans from Virginia, North Carolina, Minnesota, California; and other state local plans Georgia and New Jersey. I also examined the Americans with Disability Act and design guidance from the American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) and the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO).

In writing a plan for the City of Richmond Pedestrian, Bicycle, and Trails Commission, I researched federal law; local Virginia plans from Arlington, Roanoke, and Virginia Beach; statewide plans from Virginia, North Carolina, Minnesota, California; and other state local plans Georgia and New Jersey. I also examined the Americans with Disability Act and design guidance from the American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) and the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO).

Federal Regulations specify that minimum design standards should be exceeded whenever possible. Planning for future use means a community will not have to go back later and tear up a stretch of road in order to retrofit a future road needs. Simply put, designing for future use instead of present use saves money and effort in the long run.

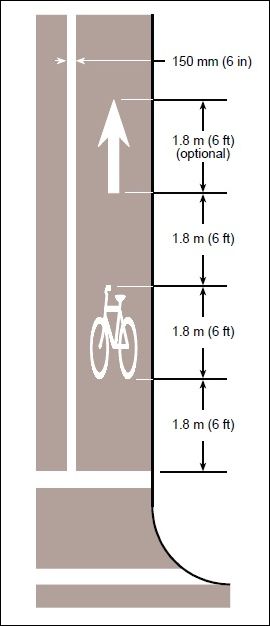

AASHTO produces the ‘Bible’ of transportation engineering, the so called ‘Green Book’. This book lists engineering and design guidelines for all manner of roads, from local neighborhood streets all the way to highways. Although it does contain some minimal design regulations, it focuses mainly on engineering. The image above is from AASHTO, and shows the focus on engineering. The designs are used by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

NACTO, a new organization, focuses on the aesthetic design of complete streets in an urban environment. NACTO is challenging AASHTO dominance in the field of complete streets design, and is now recommended by the Federal Highway Administration. A NACTO image at right shows how the organization is more aesthetically inclined than AASHTO.

NACTO, a new organization, focuses on the aesthetic design of complete streets in an urban environment. NACTO is challenging AASHTO dominance in the field of complete streets design, and is now recommended by the Federal Highway Administration. A NACTO image at right shows how the organization is more aesthetically inclined than AASHTO.

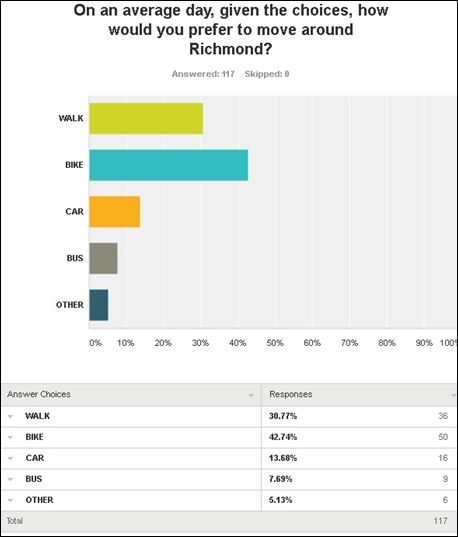

Finally, I created a survey of 10 questions and sent it out to local citizens, planners, and non-profits. Questions asked about beautification efforts, thoughts on parking in Richmond, and alternative transportation. Question eight and nine proved the most interesting (see pictures below). When asked how they are most likely to move around, 70% of respondents answered with ‘car’, and less than 15% each for ‘bike’ or ‘walking’. However, when asked how they would prefer to move around the city, the percentage of people using a car dropped from 70% to less than 15%, and walking and biking went from less than 15% each to 30% and 40% respectively. This shows that there is indeed a demand for alternative forms of transportation and the infrastructure necessary to support that demand. People want Complete Streets.

After going through the research, I recommended two goals. The first goal is to ‘Adopt and Utilize Best Practices’. This is accomplished by following three objectives.

The first objective is to ‘Focus on Existing Best Practices’, as outlined in the Richmond Strategic Multimodal Transportation Plan from 2013, also known as ‘Richmond Connects’. This includes using existing checklists and action matrices, and following the implementation strategies outlined in the document. The second objective is to ‘Adopt National Best Practices.’ Best Practices include: having a dedicated organization operating as a meeting space for different government department to come together and discuss transportation issues and complete streets; surpassing Americans with Disability Act minimum requirements whenever possible; using AASHTO and NACTO design guidelines; and using existing action matrices and checklists as part of uniform paperwork for Complete Streets projects.

The third and final objective for goal one is to adopt Context Sensitive Solutions. One size does not fit all. Not every road is meant to have a bike and bus lane and wide sidewalks. The City must look at adjacent land uses, needs of the neighborhood, and the status of the road within the wider road hierarchy to determine what uses are best suited to each particular road.

The second goal is to implement Complete Streets on a day to day basis. To do this, the complete streets organization (from objective 2 of goal 1) must come up with a series of day-to-day policies for implementing complete streets. Communication will be key in this regard; in order to implement complete streets, different departments (Planning, Utilities, Public Works) need to talk with each other and organize their efforts.

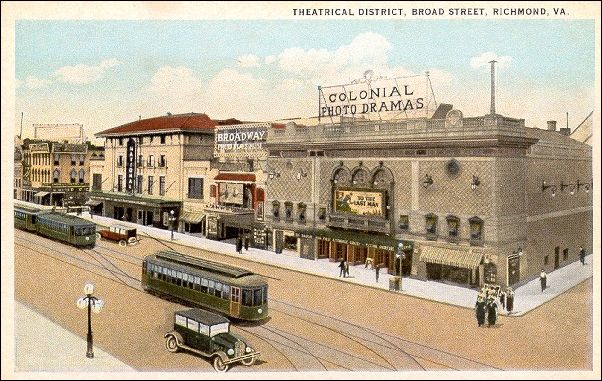

In conclusion, as the picture below shows, Richmond has a long history of multi-modal connection. Here, the streetcar, private automobile, and pedestrian share the space, while wide sidewalks and scaled lighting provide a sense of safety for people. The city has used Complete Streets before, and will continue to do so in the future.

James Newman has just graduated with a MURP Degree from VCU. He hopes to find work as a public servant in Northern Virginia.

This project was completed for the City of Richmond Pedestrian, Bicycle, and Trails Commission, as represented by Mr. Jakob Helmboldt. Mr. Newman presented his findings at the 2015 Virginia Commonwealth University Plan off.