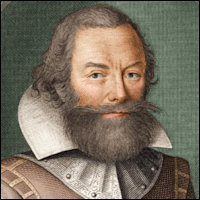

In 1602, five years before he led the Virginia Company expedition to found a colony in the new world, John Smith fought as a mercenary in a war against the Ottoman Empire. Wounded in battle, he was captured by Crimean Tatars. He and his comrades were sold as slaves — “like beasts in a market,” as he later put it. Taken to Crimea, Smith escaped into Muscovy, from where he made his way to Poland, and then circuitously back to England in 1604.

It is worth remembering Smith’s brush with slavery as we ponder the significance of the founding of the New World’s first representative assembly in 1619 at Jamestown as well as the importation of the colony’s first African slaves. There is an increasing tendency in America’s intellectual class to view the United States as irredeemably stained from its inception. It may be true that Virginia established representative government, some suggest, but who was represented? White male property owners. According to this narrative, white Americans prospered through the oppression of native Americans and black slaves. Conceived in sin, some say, the American experiment was illegitimate at its birth.

Such a perspective commits the error of viewing the American colonies in isolation from what was happening in the rest of the world and then condemning the colonists for failing to live up to the standards of 21st-century values. Before adopting such a view, let us recall what the world was like in 1619. Slavery and other forms of servitude were nearly universal. What made England and its American colonies remarkable was not their sufferance of slavery for 200 years or more but their eventual willingness to abolish it.

Slavery was especially common in Muslim lands. The Ottomans and their vassals the Tatars routinely enslaved the Slavic peoples of what is now the Ukraine, Russia and the Balkans. (The word “slave” is derived from “slav.”) The potentates of the North African coast, known to history as the Barbary Pirates, raided European ships and coastal communities in the Mediterranean. Historian Robert Davis estimates that the white slave trade between 1500 and 1800 enslaved as many as 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans (although it must be noted than any estimates are somewhat conjectural). Even Americans were not immune to this horror. James Riley, a Connecticut mariner, wrote a best-selling narrative of his 1815 shipwreck on the coast of Mauritania, his capture by local nomads, and his ordeal as a slave. Thomas Jefferson, it might be remembered, launched the United States’ first foreign intervention in its war against the Barbary pirates.

While Americans focus on the Atlantic slave trade, in which whites purchased black slaves on the western Africa coast, we cannot forget the Arab slave trade, which began in the Middle Ages and penetrated deeper and deeper inland over the centuries. Arab slavers conducted razzias for the express purpose of acquiring slaves, capturing literally millions of Bantus (the cultural-linguistic group from which most African-Americans are descended), and shipped them along Indian Ocean trade routes to the Middle East. Historians estimate that the Arabs enslaved as many as 17 million people. By comparison, the Atlantic slave trade shipped an estimated 12.5 million Africans to the New World — about 338,000 to North America.

Of course, the Africans themselves practiced slavery. It wasn’t the same kind of slavery as in the Western hemisphere, which was based upon a plantation economy that did not exist in Africa. More commonly, the practice among clan- and chieftain-based societies in Africa (and among American Indians, among others) was to capture women and children in raids on neighboring groups and enslave them as domestic servants. However, as demand increased in the Western Hemisphere for involuntary labor, some Africans saw in the slave trade a route to wealth and power. In West Africa and Angola fast-expanding kingdoms traded slaves (and sometimes ivory) for guns that provided military supremacy. Just as the Arabs did, these kingdoms acquired slaves by raiding weaker populations around them. Ironically, Europeans, who suffered high mortality rates from diseases along the West African Coast — known as the “white man’s graveyard” — did not enslave anyone. Rather, based in coastal fortresses, they purchased the slaves from local potentates. (The situation in Angola and southern Africa was more complicated. There the creole offspring of Portuguese and Africans dominated the slave trade.)

In the discussion of America’s “original sin,” most of this context is forgotten. “Progressive” revisionists never mention the millions of white Europeans who were enslaved. They never mention the Arab slave trade, which surpassed the Atlantic slave trade in the number of people enslaved. And they never mention the role of Africans in enslaving other Africans. The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Ala., which I recently visited, glides over all of this, referring obliquely only to the fact that millions of Africans were “kidnapped” and transported to the New World, without saying who did the kidnapping!

Finally, the “progressive” narrative never mentions how the trade in African slaves, and slavery itself, came to an end. Only in one nation, Haiti, did slaves free themselves through armed revolt. The abolitionist movement arose from a principle common to Christianity (mostly Protestant Christianity) and the European Enlightenment that all men were equal before god. First England abolished the slave trade, and then France, and then the United States. Then England abolished slavery, then France, and then, after a bloody civil war, the U.S. (Abolition of slavery in Spanish and Portuguese territories came later.) No African kingdom voluntarily abandoned slavery. No Middle Eastern potentate voluntarily abandoned slavery. The trade in African slaves ended only when England (and other European powers) militarily conquered the African and Arab slave states in a long-running commitment to end slavery around the world.

Yes, slavery was a part of Virginian history and American history, and we cannot ignore it. But so, too, was the fight for representative government, and so, too, was the extension of the rights won by Englishmen to other races, cultures and ethnic groups. Virginia was the place where the universal ideals of the Enlightenment were applied, at least philosophically, to all men. Rarely acknowledged, abolitionists came close during the great slavery debate of 1831-32 to ending slavery in the commonwealth. That effort led by Thomas Jefferson Randolph, eldest grandson of Thomas Jefferson, ultimately did not succeed, but it represents a current of history of which all Virginians can be proud.

Virginia did not emerge from the violence, oppression and intellectual darkness of the Middle Ages as pure and refined as a modern-day democracy. The struggle of equal rights for all took centuries — as it did throughout the world. Virginians are right to celebrate that struggle and the contributions, however limited or imperfect, of those who led that struggle each step of the way.