VCU Health System has broken ground on a $349 million outpatient facility, the largest investment in its history.

The City of Richmond has an annual budget of about $700 million a year. The city gets loads of coverage by local media. Henrico County has an annual budget of about $1 billion a year. County government doesn’t warrant the same number of column inches or minutes of air time, but local media do catch the highlights.

The publicly owned and operated VCU Health System has a budget of about $1.5 billion a year. The quality of medical care there has just as critical an impact on the lives of the Richmond-area residents as, say, schools, roads, and municipal services. Moreover, increases in hospital charges have rapidly outpaced the increase in local tax rates for years — perhaps decades. Yet no one raises a peep, and local media tell us nothing about the hospital’s internal deliberations.

My purpose here is not to dis local media, which are under tremendous cost-cutting pressure and have shrinking resources to cover the news. It is simply to suggest than an institution so large and vitally important to a community — and the same could be said of Sentara in Norfolk, Riverside in Newport News, Carilion in Roanoke, Inova in Northern Virginia, and the University of Virginia Hospital in Charlottesville — needs public accountability. Oversight is all the more imperative when an institution enjoys nonprofit status that frees it from the burden of paying property taxes, sales taxes, corporate income taxes, and miscellaneous levies and excises.

It’s fair to say that the general public knows almost nothing about how VCU is run, what it’s long-range goals are, or how well it’s doing its job. Its annual report (like all annual reports) is essentially a public relations document. The only glimmer of accountability comes from the Virginia Health Information website, which compiles hospital data and publishes some “efficiency” metrics, but provides no narrative analysis.

VCU Health generated an operating income of $136 million in fiscal 2016 — $120 million, if non-operating gains and losses are taken into account. It enjoys a protected market thanks to state and federal restrictions on competition. What is the public getting for the quasi monopoly status conferred upon VCU and the massive profits it generates? Not efficiency, that’s for sure.

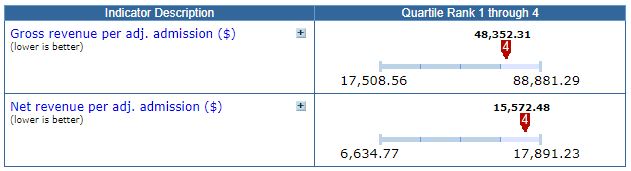

Virginia Health Information compares gross and net hospital revenues per admission, adjusting for the acuity of cases. (As a tertiary care hospital and trauma center, VCU gets a disproportionate share of the hard cases, but the VFI methodology accounts for that.) For both categories, VCU falls within the most expensive quartile of hospitals, as shown in the table above.

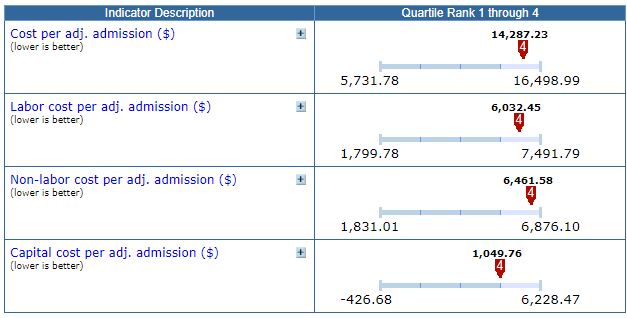

VHI also looks at underlying costs. Again, VCU consistently comes out as one of the most expensive hospitals in Virginia, whether labor cost per admission, non-labor cost, or capital cost. Other tables shows that productivity/utilization ratios fall in the bottom two quartiles.

Despite these unfavorable comparisons — which VCU undoubtedly will say are unfair, perhaps with good reason — the health system retains $120 million a year in profits (what VHI terms “Revenue and gains in excess of expenses and losses”). An industry rule of thumb is that hospitals need to retain 3% of their earnings to reinvest in new plant, equipment and technology. VCU retains 8%, a difference of about $75 million a year.

In theory, VCU could rebate that $75 million a year to the community in the form of lower charges to patients. But hospital management, with the backing of the VCU board, has chosen to invest in institutional expansion. That includes, most controversially, significant expenditures to create the Virginia Treatment Center for Children, even though philanthropist William H. Goodwin had pledged to give $350 million to create an independent children’s treatment and research hospital. VCU declined to collaborate with Goodwin, preferring to charge ahead with plans to keep the children’s hospital under its own corporate umbrella. Goodwin has not announced how he might otherwise dispose of his proposed gift, but there is no guarantee that the Richmond community will be the beneficiary.

Nonprofit hospitals, like colleges and universities, are not profit-maximizing institutions — they are prestige-maximizing institutions. Hospital administrators don’t go into the hospital business to make massive fortunes (although they do very nicely). They go into the hospital business to enhance the status of the institutions with which they are affiliated. Nonprofit status is not some magic fairy dust that makes self-interest and self-dealing disappear. As with the quest for profit, there is no limit to how much money hospital leaders will spend to advance their institutional standing in a never-ending race with other institutions seeking to do the same.

These massive revenue- and profit-generating enterprises — VCU is hardly alone — operate with no effective restraint or public oversight in Virginia. For time immemorial, Virginia’s news media has defined its mission as holding government entities accountable. It’s high time they begin holding nonprofit universities and hospitals accountable as well. But they can’t — they lack the resources. As nonprofit universities and hospitals metastasize, growing swaths of Virginia’s economy function in darkness.