This first section of this post by James A. Bacon is cross posted from the Datamorphosis blog…

Recent years have seen the rise of what European Union officials are calling “citizen science,” a phenomenon in which amateurs, enthusiasts and others acting in a non-official capacity collect data (usually environmental data), participate in the design of projects and subject the data to analysis for public benefit. This trend is gaining momentum as the cost of acquiring environmental sensors drops for everything from CO2 levels to water quality, as mechanisms arise for citizens to share their data online and as activists in one location inspire citizens in another.

Indeed, there is so much activity that the European Commission Joint Research Centre convened a “Citizen Science and Smart Cities Summit” in Ispra, Italy, this past February. The Centre now has published a report, “Citizen Science and Smart Cities,” summarizing the main findings and recommendations.

There often is overlap between municipal smart-cities programs — an increasing number of European cities are setting up sensor networks to measure key environmental quality indicators — and grassroots citizens initiatives. Also, notes the report, there is “increasing recognition in the scientific community that to address the key challenges of the 21st century we need to move beyond the boundaries of discipline research and engage in research that is multi-disciplinary and participatory.”

Unfortunately, there has been little synergy between citizen and municipal initiatives. It is difficult to compare the results of citizen science and smart cities projects or translate findings from one context to another. Moreover, citizen data often disappears after the projects wind down, making it difficult to reproduce results.

The report makes a number of recommendations. One is to map citizen-science and smart-cities projects and generate a semantic network of concepts between the projects to facilitate searches of related activities. Another is to create a repository for data, software and apps so they can be maintained beyond the life of projects and be made shareable.

Bacon’s bottom line. The Euro-weenies are way ahead of most American metropolitan regions (especially Virginia metros) in applying sensors, wireless and Big Data — essentially, the Internet of Things — to the business of running their cities. Admittedly, much of Europe’s activity is top-down, fostered by national-government and European-Union subsidies, but a lot of it — especially the citizen science piece — is bubbling from the bottom-up. I see next to nothing here in Virginia, whether top-down or bottom-up.

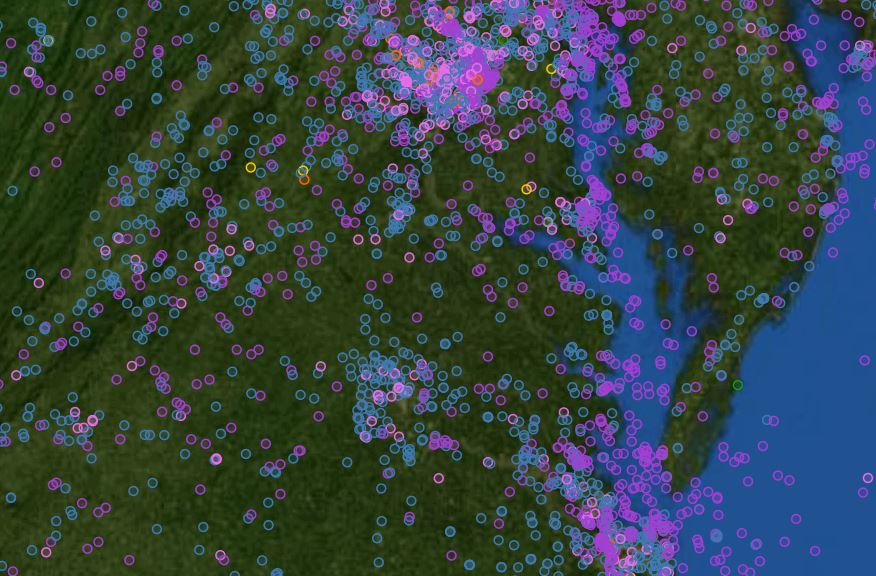

The map at the top of this post comes from Thingful, a search engine for the Internet of Things (IoT). Each data represents a data set that someone has posted to Thingful. Follow this link to see the density of published data sets in Virginia compared to that of other cities around the world.

A region’s ability to compete in the global economy depends upon its collective capacity ability to boost productivity and innovation. The IoT is supplying a new set of tools by which to advance those aims. If we snooze, we lose.

While regions in Europe, Asia and even Latin America race to embrace IoT technology and reinvent themselves (the new Indian government has announced its intention to build 100 smart cities), I get the feeling that Virginia’s metropolitan regions are lollygagging along. The Internet of Things is not part of the public discourse. I see nothing written about it in our newspapers and magazines. Whenever I write about smart cities, I get next-to-zero feedback. If the readers of Bacon’s Rebellion aren’t interested — and you are indubitably the smartest and most perceptive citizens in the commonwealth — what hope is there?