by James A. Bacon

More than 600,000 Virginians have filed for unemployment claims since mid-March, when the COVID-19 epidemic started hitting Virginia and Governor Ralph Northam’s emergency decrees shut down large sectors of the economy. That’s roughly one person out of seven in the state’s workforce. After the first wave of closings, the number of new jobless claims has been shrinking. One can hope that we have seen the worst. Once federal helicopter money floats to earth and Northam shifts to a cautious, step-by-step rollback of the virus-control measures, one can hope, businesses will start rehiring.

Richmond economist Chris Chmura expects the national economy to contract at an annualized rate of 18.4% rate in the current economic quarter, another 1.0% in the third quarter, and then to begin growing again. “Employment at utilities, professional services and company headquarters should be back to 90% of pre-coronavirus levels by the fourth quarter,” she writes.

I hope Chmura is right. Judging by the snapback in the stock market, a lot of people seem to agree with her. I’m not counting on it. There’s a lot more bad news to come out.

That bad news comes in two categories — events we can reasonably predict, and events we don’t see coming. Let’s start talking about the kind of news we can predict.

Capital spending. Business hates fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD), of which there is plenty. When faced with FUD, the vast majority of businesses typically by conserving cash. Publicly held companies halt their stock buybacks (something no one will miss) and cut dividends (something that many people will miss). Most importantly, they will delay capital spending. They won’t necessarily halt projects in process, but they will put future planned projects on hold.

Thus, for example, a construction contractor might have a solid project backlog extending six to mine months out. Those projects are still ongoing, and the construction workers are still employed. But as other businesses (and governments) start conserving cash and putting future projects on hold, if not canceling them outright, at some point that contractor’s work will fall off a cliff. Construction contractors are only the most visibly affected. Companies that supply equipment and spend heavily on big infotech projects will be impacted similarly.

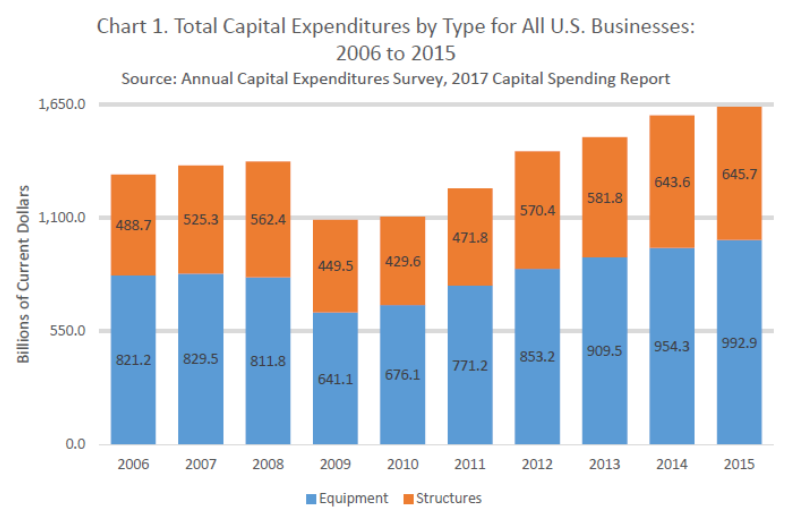

This chart from the U.S. Census Bureau shows how important capital spending is to the economy, and what happened the last time, in 2009 and 2010, the U.S. had a major recession.

Depending upon the level of FUD and offsetting federal helicopter dollars, the falloff in capital spending could be in the neighborhood of $600 billion to $700 billion. (That’s an order of magnitude guesstimate based on five-year-old data).

In the last recession, utilities were the only sector of the economy that proved immune to the downturn. The manufacturing, mining, and transportation/ warehousing sectors saw significant declines in capital spending, while even the health care and information sectors were negatively impacted.

Manufacturing. Businesses aren’t the only ones who conserve cash in times like this. So do consumers. When people have been laid off, or are worrying about losing their jobs, people buy less stuff. When they buy less stuff, the people who manufacture that stuff suffer — not right away, but as inventories build up and the full dimensions of consumer cutbacks become clear. Thus we get stories like this from the Wall Street Journal today:

Factory furloughs are becoming permanent shutdowns, a sign of the heavy damage the coronavirus pandemic is exerting on the industrial economy.

Makers of dishware in North Carolina, furniture foam in Oregon and cutting boards in Michigan are among the companies closing factories in recent weeks. Caterpillar Inc. said it is considering closing plants in German, boat-and-motorcycle-maker Polaris Inc., plans to close a plant in Syracuse, Ind., and tire maker Goodyear Tire & Rubber plans to close a plant in Gadsden, Ala.

Mortgage markets. Meanwhile, the surge in joblessness has led to a corresponding spike in nonpayment of mortgages, putting stress on the financial companies that supply that debt. (Similar things are likely credit card companies and financiers of auto loans.) Thus, we get stories like this also from the Wall Street Journal today:

The U.S. mortgage market still functions much the same as it did before the last financial crisis. The coronavirus pandemic has exposed its cracks. The virus has forced millions of homeowners to stop making their monthly payments. At the same time, many mortgage companies aren’t positioned to help their customers though the economic collapse.

Many of them are nonbanks that don’t have deposits or other business lines to cushion the blow, and they have raised concerns that fronting payments for struggling borrowers will quickly drain them of capital.

The commercial real estate sector is likewise threatened as thousands of tenants — restaurants and small retailers — fall behind on their rents, or stop paying entirely.

Federal helicopter dollars are meant to inject liquidity into the system to prevent the system from freezing up. Maybe the Fed’s largely indiscriminate approach will work, maybe it won’t.

Corporate leverage. A a rational response to the ultra-low interest rate policies pursued by the Federal Reserve Board over the past decade, U.S. corporations have been substituting debt for equity on their balance sheets. They’ve been buying back and retiring stock and borrowing more. As a consequence, they are more leveraged than almost any time in U.S. economic history. Corporate debt was nearing $10 trillion toward the end of 2019.

Many businesses — most notoriously in the oil & gas sector — have borrowed heavily, and repayment of much of that debt now is looking precarious. Regulated by the federal government, the big money-center banks seem to be in sound financial condition. But the riskier lending has moved to unregulated “nonbank” entities. No one really knows what is out there, or how a collapse at one institution could trigger a domino effect on other institutions. While it is dangerous to venture any predictions, it is safe to say that a huge amount of risk lurks in this shadowy realm.

What we don’t know. While a handful of epidemiologists predicted that something like COVID-19 was likely to create a global pandemic at some point, very few people in government or the business world had processed that possibility. The U.S. Congress and the media were busy trying to impeach the president, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average was closing in on 30,000. (I recall a cover story of Barron’s magazine speculating how soon the Dow would hit 30,000, and how far beyond the market was likely to shoot — as any contrarian knows, a sure sign of impending doom). For nearly all investors, the pandemic came out of the blue. No one was prepared for it.

Just as the 2008 recession triggered hidden financial linkages that transmitted shocks from one sector of the economy to another, so might the COVID-19 recession. The global economy is more leveraged than it was ten years ago. Therefore, it is more vulnerable to systemic shock. Those linkages have not yet been exposed, but that’s not to say there aren’t there.

So, what does it mean? Governance at the federal level is hopeless. The only thing Republicans and Democrats can agree upon is to spend and borrow at unprecedented levels in the desperate hope that throwing together hastily concocted programs backed by unlimited trillions of dollars might salvage the economy. Washington won’t change, and Virginians, comprising only one out of 40 Americans, are politically powerless to make it change. What Virginians can do is create an island of relative calm and tranquility by passing responsible budgets, pursuing growth-friendly economic policies, and relaxing restrictions that prevent people from getting back to work — in other words, by doing things that are as foreign to the ruling class as COVID-19 is to the human body.