by Dick Hall-Sizemore

by Dick Hall-Sizemore

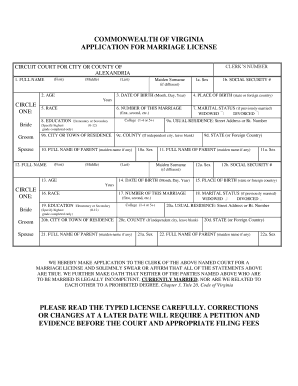

Well, Virginia made the national headlines again last week and over the weekend. This time it was over the requirement that couples applying for a marriage license list their race on the application. And Attorney General Mark Herring was the hero, saying that, despite what the law said, the couples did not have to do that. (NYT, WP, RTD, as well as all the networks).

On the face of it, the state could make a case that gathering information about the race of people getting married serves a legitimate purpose by providing data for state demographers and sociologists. But, because “race” can be a vague concept and applicants self-identify their race, any data collected has become meaningless. Apparently, each county can compile its own list of categories from which applicants choose. According to newspaper reports, Rockbridge County had a list of approximately 200 “races”, including American, Aryan, Hebrew, Islamic, Mestizo, Nordic, Teutonic, Moor, and White American.

Most people will dismiss this whole episode as somewhat silly, at best, or another holdover from the state’s problematic past. However, the story involves a much more serious, and worrisome, issue.

The Attorney General has apparently decided that he can overrule a law he feels is wrong. I am anxious to see his legal rationale in telling couples they do not have to list race on their marriage applications. No official Attorney General’s opinion has been posted on the office’s website nor does the website list any news release on this subject.

Before looking at what the Attorney General did say publicly, let’s look at what the law says:

- 32.1-267—“For each marriage performed in the Commonwealth, a record showing personal data, including but not limited to age and race of the married parties, the marriage license, and the certifying statement of the facts of marriage shall be filed with the State Registrar as provided in this section.” [Emphasis added]

- 20-16—“The clerk issuing any marriage license shall require the parties contemplating marriage to state, under oath, the information required to complete the application for marriage license.” [Emphasis added]

In his comments, Herring, at best, does what people hate about lawyers—gets real picky and ignores the commonsense meaning of words. At worst, he simply overrides a statute he finds obsolete or inconvenient. (Just to be clear, I am basing my comments on media reports. I could not find a copy of the memo Herring sent to clerks and the media.) Let’s parse those comments:

- No specific requirement that applicants have to provide information about race—But, there certainly is such a requirement. Sec. 20-16 says that clerks shall require the applicants to state the information required to complete the application, and, Sec. 32.1-267 explicitly says that race shall be recorded on the application.

- “…law does not require a clerk to refuse to issue a marriage license when the applicant declines to identify his or her race.’’—He is correct. But, common sense tells one that a person refusing to provide the required information is not entitled to the license. If that is not the case, look at the position in which it puts the clerks. The law requires the clerks to submit to the State Registrar [of Vital Statistics] a record showing the information concerning the marriage, including the race of the parties. If the clerks cannot compel the parties to provide the information, how can the clerks comply with the requirement placed upon them? Now, let’s follow the Attorney General’s argument to its logical conclusion. If the applicants can refuse to provide information about their race, doesn’t that logic also apply to other information on the application, such as age or even name?

Disclosure: I am not a lawyer. However, I have spent a career spanning more than 40 years drafting and interpreting statutes in both the legislative and administrative branches. I feel as if I am on solid ground in my comments, especially in light of the reported comment of the lawyer representing the plaintiffs challenging the statute, “I’m not too sure about the actual legality of [Herring’s] directive….”

My Soapbox—The requirement may be unnecessary; it may even be offensive. But it is the law. It is up to the legislature to change or repeal the law or the courts to declare it unconstitutional. Everyone should be deeply worried when an elected official, especially an Attorney General, chooses to override a statute for political reasons.