by James A. Bacon

And now for an answer to the fascinating question posed by Hamilton Lombard on the StatChat blog: why African-Americans living in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware have the highest median incomes anywhere in the United States (see “A Demographic Mystery“)…. Ultimately, he says, the answer can be traced to the history of slavery in the Chesapeake region that gave rise to a large population of free blacks.

At the risk of oversimplifying (I urge you to read his full blog post), Lombard’s argument goes like this: With the introduction of tobacco to Virginia in the early 1600s, Virginia was the first state on the North American mainland to develop a plantation economy. Most slaves at that time originated from Angola. Because that region of Africa had been under Portuguese influence since the 1400s, many of the slaves were Christian, which may have entitled them to different consideration than pagans. Moreover, English common law prohibited slavery. Therefore, the first Africans in Virginia, like whites, were engaged as indentured servants and gained their freedom after working for a set time.

(Lombard doesn’t mention this but it fits with his theme: Many followers of Nathaniel Bacon during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 were freed African servants and slaves, who made common cause with freed white servants and small farmers.)

The institution of slavery did not cohere into the chattel form with which we are familiar until 1705 when the Virginia House of Burgesses codified a system of forced labor for non-Europeans and non-Christians. By that point, the slave trade had shifted to West Africa where Africans were far less likely to be Christianized.

I would expand upon Lombard’s argument as follows. Chesapeake slavery was built largely around tobacco plantations. By the late 1700s, tobacco cultivation had exhausted the soils, and the industry went into sharp decline, leaving farmers and plantation owners with a large surplus of slaves. At the same time that slaves were losing value as a means of production, many slave owners were feeling the contradiction between their ownership of other human beings and their belief in egalitarian, revolutionary ideas. Manumission became a fairly common practice, peaking around 1800. (I have a Bacon ancestor living in Sussex County, Del., who, according to family lore, granted his slaves their freedom after his death.)

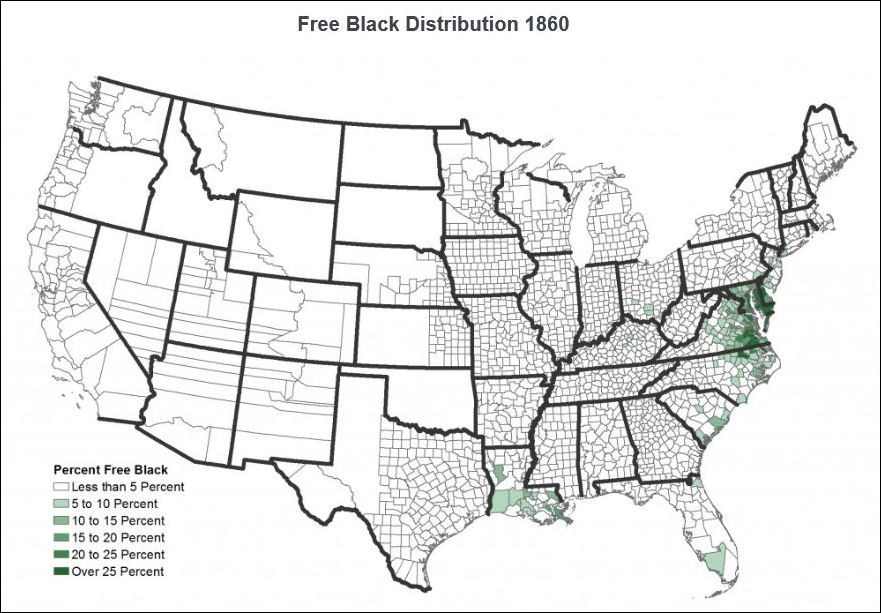

Everything changed around 1800. Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1794, making possible the profitable cultivation of cotton — but not in the Chesapeake states, which were too far north to grow the plant. And then the United States banned the Atlantic slave trade in 1808. The institution of slavery in the Chesapeake region gained a new lease on life as slave owners sold their slaves to markets in the deep south. The end result was a demographic pattern by 1860 in which 10% to 25% or more of the black population in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware counties were free but, outside a few counties in North Carolina, free blacks were almost unknown elsewhere.

That freedom, argues Lombard, gave Chesapeake blacks a head start in the accumulation of property and wealth. A glance at the maps he produces shows that across most of Virginia, the black farm ownership rate in 1920 was over 50% across the state and over 75% for big chunks of it — far higher than anywhere else in the country, even the North. Another map shows that the black home ownership rate in 1940 exceeded 60% in much of Virginia — again, far higher than anywhere else in the country. Lombard suggests that the lack of a sharecropping economy in Virginia may explain the difference.

The analysis at this point gets a little fuzzy because, based upon an eyeballing of Lombard’s maps, the rate of farm- and home-ownership in Virginia were considerably higher than in Maryland and Delaware, so there may have been other factors at work than the percentage of free blacks and/or the lack of sharecropping institutions. Lombard doesn’t address this issue. Could Virginia’s Jim Crow laws been less restrictive than those of Maryland or Delaware? Were Virginia blacks more highly educated? Whatever, the reason, it can hardly be coincidental that Richmond, where many blacks proudly trace their ancestry back to the free black population of the ante-bellum era, became known as the “Harlem of the South.”

Any analysis also need to consider the massive early 20th-century migration of Southern blacks to cities in the Northeast and Midwest, and then the subsequent migration of blacks back to the South, both of which created a large mixing effect. While some Virginia blacks trace their roots back to free blacks living in the state in 1860, how many do?

In sum, Lombard’s argument is incomplete. Not wrong, just incomplete. His hypothesis — positing a link between the percentage of free blacks in the population in 1860 and the economic well being of Virginia blacks today — is fascinating and inherently plausible. It would make a great PhD thesis.