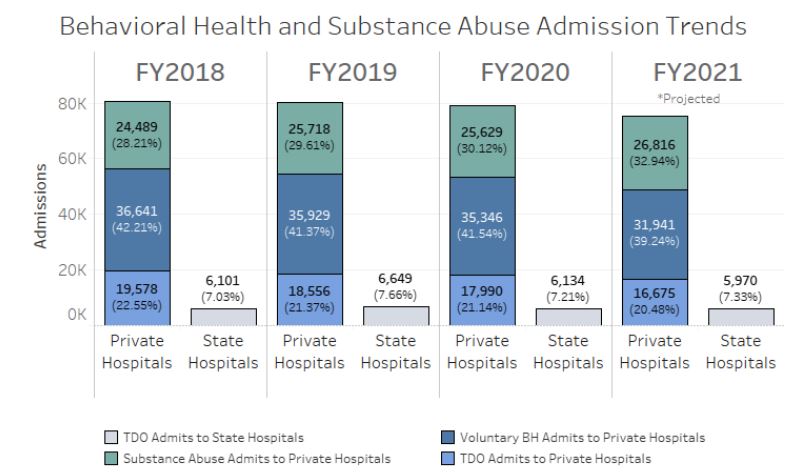

Despite rising incidence of mental illness and substance abuse, admissions to hospitals in Virginia has trended lower in recent years. Something is broken. Source: Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association

by James A. Bacon

The story made big headlines earlier this month when the Northam administration announced that five of the Commonwealth’s eight mental health institutions have stopped taking new patients. Two things are happening to make a chronically bad situation worse. First, the number of patients referred to state hospitals through Temporary Detention Orders (TDOs) has soared — from 3.7 patients per day in FY 2013 to 18 per day currently, or a 392% increase. Second, the hospitals are suffering staff shortages, in part due to the COVID-19 epidemic but also because “the level of dangerousness is unprecedented,” according to a letter from the Virginia Department of Behaviorial Health and Development Services to partners and providers.

“There have been 63 serious injuries of staff and patients since July 1 and we are currently experiencing 4.5 incidents/injuries per day across the state facilities,” the letter stated. Employees are quitting. One facility, the Commonwealth Center for Children & Adolescents, can safely operate only 18 of its 48 beds.

Similar supply-and-demand issues are spilling into the private hospital sector. Private psychiatric hospitals, which provide acute short-term care, are experiencing a similar imbalance between demand for psychiatric facilities and a labor shortage.

The social isolation caused by the COVID-19 lockdowns spurred a surge in mental illness and substance abuse, as illustrated by the 41% increase in drug overdose deaths in Virginia last year. Counterintuitively, admissions to private facilities have decreased over the past five years. Why? Because patients on longer are staying longer. The average length of stay now exceeds seven days, an 8% increase over two years ago, according to a letter from Virginia Hospital and Health Care Association President Sean Connaughton to legislators.

Cases are becoming more complex, VHHA spokesman Julian Walker explained to Bacon’s Rebellion. Mental health issues are more likely to be compounded by substance abuse issues, which may in turn be compounded by cognitive challenges or health issues. Increased complexity requires treatment by multidisciplinary teams and takes longer to resolve.

So, what happens when patients requiring longer-term treatment are blocked from entering the state facilities? They create back-ups in the hospital emergency rooms through which many of them cycle. The problem has become so severe that patients in some hospitals are being held in emergency room beds as long as 12 to 18 hours, Walker said. In other words, the crisis in state facilities has a cascading effect.

The process for determining who gets assigned where is mediated by a complex of state laws and regulations. Hospitals can’t assign patients willy nilly wherever they want. Cases must be reviewed and approvals must be gained. One avenue for committing patients is the emergency custody order or ECO, which involuntarily commits individuals who are incapable of making informed decisions. The issuance of ECOs has been increasing, says Walker. Another is the Temporary Detention Order , which requires individuals to receive hospitalization for further evaluation. Those, he adds, trended flat for private hospitals even as they have increased for state hospitals.

There is a lot of finger-pointing going on as state hospitals, private hospitals, jails and prisons, and community health programs try to dish off patients — and the attendant financial costs for those without insurance — to one another. The system in Virginia is under tremendous stress from the increase in both mental illness, substance abuse, suicides and drug overdoses aggravated by the social isolated associated with COVID-19. There are likely longer-term forces at work, too, as rapid technological, economic and cultural change causes increasing disruption to families and communities.

If there were easy answers, someone would have figured them out. The problem doesn’t lend itself to bumper-sticker solutions. But I would say this: If you want to see what the mental health/substance abuse crisis could look like, cast your eye upon the tent cities of California filled with tens of thousands of homeless people, many of them mentally ill or addicts of some kind. Surely, Virginians can agree on one thing: We don’t want that here.