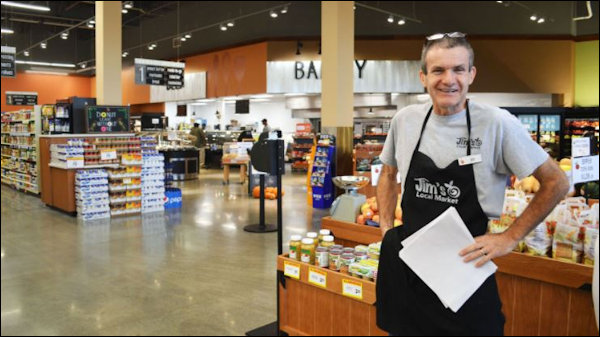

Jim Scanlon at his Newport News store. Photo credit: Richmond Times-Dispatch

Poor Jim Scanlon. He bought into the conventional wisdom that food deserts are a supply-side problem — an unwillingness of grocery store operators to locate in inner cities. Hoping to remedy that deficiency, the idealistic former Ukrop’s executive opened Jim’s Local Market in a low-income neighborhood in Newport News in May 2016.

Now, a year and a half later, he’s closing the store, reports the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Explains Scanlon: “It’s just that the sales are not there, and the profitability is not there. It’s not working out.”

Bacon’s bottom line: Food deserts are a demand-side problem, not a supply-side problem. Poor people, like many Americans, just don’t like broccoli, kale, quinoa, cauliflower, or other trendy superfoods that go in and out of fashion among the cultural elites. Pleasures in life in the inner city are far and few between, and the poor, also like many Americans, gravitate to food that provides immediate gratification… Which means they gravitate to processed food loaded with salt, sugar and fat that tastes good. Go into any convenience store or corner grocery in the east end of Richmond and you’ll see aisles stocked with snack foods and soft drinks — the kind of food people are willing to spend their money on.

If you want poor people to eat healthier food, putting healthy food in front of them won’t work. You can literally give away the carrots and squash, and many people won’t eat them. Not only have they not acquired the taste, they have lost the cultural knowledge of how to cook them.

Tricycle Gardens in Richmond was launched to create urban gardens and create a supply of healthy vegetables that poor, inner-city residents should include in their diets. The idea behind the nonprofit was the old give-a-man-a-fish-and-you-feed-him-for-a-day, teach-a-man-to-fish-and-you-feed-him-for-a-lifetime philosophy. The group built small, “key-hole” gardens that anyone could install in their backyard and reap a bounty of vegetables. I don’t know if Tricycle Gardens had many takers, but let’s just say, I have seen little evidence of a horticultural revolution sweeping through Richmond’s inner city. The last time I communicated with the group — it’s been a couple of years — its leaders were recognizing that they had to work on the demand side. The outfit was talking about giving cooking classes to teach how to make yummy dishes out of brussel sprouts, and it was partnering with local schools to get kids involved with raising garden vegetables, learning about nutrition, and excited about eating healthy food. If we want poor Virginians to eat more healthy food, that’s the kind of slow, plodding change we need to undertake.

Another well-meaning group is investing a grocery store in Richmond’s East End. The building is now under construction. With all the gentrification taking place in the East End, that venture may find enough customers among young urban professionals to sustain itself. Otherwise, it will likely meet the same fate as Scanlon’s Newport News enterprise. Simply put: The enterprise is addressing the wrong problem.

My wife and I were walking along the James River this morning when we came across this beautiful little flower, which appears at roughly life size in the photo to the left. We have no idea what it is. Does anyone recognize it?

My wife and I were walking along the James River this morning when we came across this beautiful little flower, which appears at roughly life size in the photo to the left. We have no idea what it is. Does anyone recognize it? The flower most often appeared in clumps, like that seen at right. It clearly prospers in the shade.

The flower most often appeared in clumps, like that seen at right. It clearly prospers in the shade.