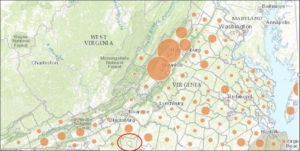

Farm sales by Virginia locality 2012, taken from the StatChat blog. Red circle shows location of Martinsville/Henry County.

The Patrick Henry Community College in Martinsville has dropped its agricultural degree program along with certificate programs in horticulture and viticulture. Between declining enrollment in the programs and state budget cuts, it is no longer feasible to offer the courses, President Angeline Godwin told the Martinsville Bulletin.

Many people might view this flotsam in the torrential current of news coverage as utterly without interest. To Bacon’s Rebellion, the story is imbued with deeper significance in at least two ways.

Market-responsive education. First, it shows how at least one community college is responsive to market forces. Each degree program is the functional equivalent of a product line. The agriculture/horticulture/viticulture product line wasn’t selling in the Martinsville-Henry County area and could not be operated at a profit. So PHCC eliminated the program. Wise decision. As the map above shows, there was not enough farming activity in Henry County in 2012 to register any farm sales. While there still may be some hobby farms, career farming in that part of the state appears to be a defunct vocation.

Virginia’s colleges, universities and community colleges offer literally thousands of product lines — everything from two-year degrees in agriculture to four-year degrees in Tibetan language studies. Some programs are in greater demand than others. Some programs are more “profitable” than others — profitable in the sense that the share of tuition revenue attributed to class enrollment exceeds the cost of employing faculty and administrative overhead to teach them.

Public colleges and universities in Virginia must seek approval of new degree programs by the State Council for Higher Education in Virginia — and SCHEV does not act as a rubber stamp. The council scrutinizes requests and sometimes sends them back for revision or reconsideration. But once an institution gets the OK for a degree program, SCHEV does not monitor its ongoing progress. I have seen no evidence that even the Boards of Trustees of the institutions themselves track the enrollment numbers in degree programs. Do college administrations even compile these numbers? Surely, they do, for they must have some rational basis for deciding how to allocate resources for hiring faculty. But if they do, the public never sees these numbers.

The PHCC article reminds us that some degree and certificate programs fall out of favor. PHCC made a good business decision by shutting down three for which demand had evaporated. But note this: The college acted out of the necessity caused by cuts in state support. Would it it have acted otherwise? Who knows?

My question is this: How many other zombie degree programs are there in Virginia’s system of higher education that are shuffling around half-dead? Could Virginia’s colleges and universities combat runaway costs by chopping out the deadwood?

The decline in farming. The second lesson to learn from this seemingly innocuous article is that inhabitants of what we think of as “rural” Virginia appear to be losing interest in pursuing rural livelihoods, the most notable of which is farming. Based on farm sales, the only part of Virginia where large-scale agricultural operations takes place is the Shenandoah Valley.

When we think about rural economic development in Virginia, one would think that farming would be a major underpinning of the economy. After all, one thing rural Virginia has is a lot of land. Inexpensive land. And Virginia has water. We don’t have to fight wars over water rights like farmers do in California and the Inter-Mountain West. As manufacturing jobs dry up, why aren’t people turning back to farming to make a living? Is the work too hard — it is work that Americans don’t want to do anymore? I don’t know the answer. But the question seems important to ask.