by Matt Hurt

On November 7, JLARC released the Pandemic Impact on Public K-12 Education. In this report, the challenges of educating students during the pandemic were outlined, and policy prescriptions were provided to mitigate these issues in the future. From the perspective of an educator, the report adequately addressed some issues, but failed to provide an in-depth analysis of various problems. This lack of understanding of these problems provided policy prescriptions which will likely miss the mark.

To be sure, this report highlights some major problems that have impacted student outcomes in Virginia. Chronic absenteeism, teacher shortages, and virtual instruction all negatively impacted student outcomes across the Commonwealth in 2022. While other factors highlighted in the report also attributed to lower performance in 2022, I will focus on these three in this paper.

Attendance

JLARC rightly reports that poor student attendance is a significant problem. If students don’t come to school (or truly participate virtually), teachers can’t teach them.

While there is no valid rebuttal to this argument, we don’t have accurate attendance data from 2022. In most of our schools, teachers are responsible for marking students present or absent each day. Pre-pandemic this was done in a relatively reliable manner: if the student was not in class at the time role was taken, the student was marked absent. In 2022, some students were virtual, and attendance criteria varied wildly across the state. Some divisions required students to submit a specific percentage of their work, while others simply required students to log into their Zoom session to be counted present. Many teachers reported teaching virtually to blank screens, as students would log their computers into the Zoom session and then do something else. Many divisions scheduled virtual instruction days during inclement weather, and this also made accurately accounting for student attendance difficult.

Chronic absenteeism was difficult to effectively address prior to the pandemic. The Code of Virginia requires compulsory school attendance for children in Virginia. There are a number of requirements for Virginia educators to ensure our students attend school regularly, such as conducting parent meetings when students are absent too many days or filing a truancy petition in court.

The long and the short of it is that the pandemic trained many of our students to be truant. The Governor closed schools during the fourth quarter of 2020. Students were liberally allowed the choice of in-person or virtual instruction, even if they didn’t have the capacity (Internet access, device, family structure) to participate virtually. Quarantine protocols required many students to miss school for 10-day spans on multiple occasions last year.

As with most situations, including attendance, we have a carrot (incentives to get students into schools) and a stick (repercussions for truancy). Unfortunately many if not most juvenile and domestic court judges in Virginia fail to effectively address truant students in court. Many school truancy officials report that the most frequent judgment meted out in court to our truant students is a stern lecture, which has proven to be ineffectual. The majority of our teachers and administrators work diligently to make their classrooms and schools safe and inviting environments for students.

The more schools focus on attendance, the less time they have to focus on instruction. If we have a compulsory school attendance law, and schools are doing their part, shouldn’t the court system also shoulder its share of the burden and support schools in this endeavor? If truant students and their families don’t face any negative consequences, why would they change their behavior?

Teacher/Staffing Shortages

According to our calculations, 26% of the variance in SOL proficiencies among Virginia school divisions could be explained by teacher vacancies. Unfortunately, there are significantly more unfilled positions this year than last.

Twenty-six years ago when I entered the field of education, many prospective teachers typically worked one or more years as an instructional aide prior to getting a full-time teaching job. This was due to the fact that there were more teaching candidates than open teaching positions each year. In fact, it was not uncommon for many divisions to receive ten or more applications for each open elementary teaching position.

As the JLARC report outlines, this favorable condition no longer exists. There are fewer candidates coming into the teaching profession each year, and since the pandemic, teachers have been leaving the field at higher rates.

First, educators do not enter the field to get rich. However, there is a salary tipping point that each potential educator considers before getting into education. For some folks that figure is lower, and higher for others. I suspect that many prospective teachers with other opportunities pursue opportunities that are more financially lucrative.

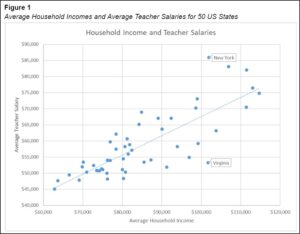

As we recently discovered, Virginia is the least lucrative state in the country to be a teacher when comparing average teacher salary to average household income. Figure 1 displays the fact that while New York’s average household income is only $199 more than in Virginia, New York teachers make on average approximately $37,000 more per year than Virginia teachers.

Figure 1

Average Household Incomes and Average Teacher Salaries for 50 US States

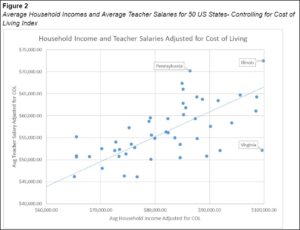

Even when controlling for the cost of living in each state (average household income and average teacher salary), Virginia is still the least lucrative state in which to teach.

Many have praised the 10% raise the General Assembly approved during the 2022 legislative session. While this is certainly a good start, this year, even with the 5% raise provided in the first biennium, educator salaries have not kept pace with inflation. Even after considering this raise, educator purchasing power is less than it was last year. In other words, salaries in real terms (controlling for inflation) are lower this year than last.

While salaries certainly play a role in decisions to enter into or remain in the field, so do working conditions. Schools in which teachers can’t wait to get into the building each day retain their teachers at higher rates than schools with less than optimal school cultures. We find that schools which value their teachers as professionals, allow them autonomy in their instructional decision-making, and genuinely include them in school decisions typically have a waiting list of teachers from other schools who want to work there.

JLARC’s recommendations for signing and retention bonuses and tuition assistance are steps in the right direction, but the fact that they recommended these be temporary is a concern. The salary incentive structure problem is likely not temporary, and if we expect our classrooms to be fully staffed, appropriate incentives must be offered. It is also not likely that the recommendation to review licensure requirements and processes will improve our situation. However, the qualifications could be lowered in order to bring in a different cohort of teachers who would not have met the previous requirements. Obviously lowering standards brings another set of problems that will likely yield worse outcomes.

It is unfortunate that JLARC didn’t make a recommendation to improve working conditions. Many things could be done to address this at the school, division, and state levels that could improve this metric, as evidenced by some of our most successful schools and divisions.

Virtual Instruction

According to our calculations, the amount of in-person instruction offered to students in 2021 combined with the poverty rate of divisions accounted for 47% of the variation in SOL outcomes. Anecdotally, our teachers and administrators reported that some families had structures in place to ensure that their children attended to their studies and others did not. While some of this was related to access to the Internet or devices, the biggest issue was simply having an adult to make sure the kids did their schoolwork. Many of our families spend a significant amount of time simply trying to make ends meet, and may not have the time or the understanding necessary to ensure their kids participate virtually. Some of our families struggle with drug/alcohol dependency, and are therefore unavailable for their kids.

JLARC recommends providing templates for online instruction and providing professional development to help educators be more effective online teachers. While there is nothing wrong with these ideas, they really don’t address the root problem. Many kids need the proximal control of teachers to ensure they do their work, as no one in their home provides that structure.

A better recommendation would be to ensure students without support structures at home have access to in-person instruction during any disruptions that would cause schools to transition to virtual instruction. For these students, this would be their only hope of receiving the instruction they need. If left to their own devices, these students would find more engaging activities than school work in which to invest their time. The most engaging instruction pales to other opportunities that are available when students get to choose what to do.

Matt Hurt is director of the Comprehensive Instructional Program, a coalition of non-metropolitan school districts.