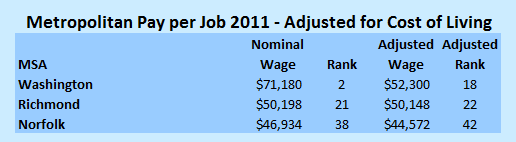

In 2011 the Washington region was the second most prosperous Metropolitan Statistical Area in the country when ranked by the average annual wage. But adjust wages for the cost of living, and the region fell to 18th place among the nation’s largest 51 largest MSAs, according to an exercise conducted by economic geographer Joel Kotkin.

Richmond lost ground, too, falling one notch to the 22nd place, while Hampton Roads fell four notches to 42nd place. Virginia, it appears, has a cost of living problem. We celebrate our relatively high incomes but tend not to ask what quality of life those wages bring us.

These findings touch upon a point that I have made off and on at Bacon’s Rebellion for many years. There is more to building prosperous societies than maximizing incomes. A balanced strategy for building more prosperous, livable and sustainable communities entails increasing incomes and restraining the cost of living.

While I agree with him on that fundamental point, it’s important to root around in the weeds to gain a more acute understanding of metropolitan dynamics. Kotkin is a big defender of the suburban status quo. He advocates less restrictive land use policies that reduce the cost of developing land and building houses — presumably policies like those practiced in no-zoning Houston, Texas, where lower living costs vaulted the region to the top of his list. And I would agree. As I argued in “Smart Growth for Conservatives,” we do need fewer land use restrictions here in Virginia.

But there’s more to the story. Kotkin draws no distinction between transportation-efficient and transportation-inefficient development. He seems just fine with the sprawling, land-intensive pattern of growth that has characterized most of American suburbia for the past half-century. But he omits something very important from his analysis: It is meaningless to analyze the cost of housing separate from the cost of transportation.

Housing on the metropolitan periphery sells for less on a cost-per-square-foot basis than housing in the core, where the underlying land is more valuable. But the cost of transportation — longer commutes, more miles between stores and other amenities — is higher. Kotkin uses Bureau of Economic Analysis “purchasing power parity” data to adjust for regional cost-of-living differences, which, if I understand the BEA methodology correctly, applies the same weight for spending categories across all urban regions. In reality, the weight for transportation spending varies from region to region.

As a Richmonder, I love the idea that metro Washington wages are only a sliver higher than Richmond wages when adjusted for the cost of living. But I’m not buying it. Yes, housing is significantly cheaper here. The same may be true of transportation when it comes to the cost of purchasing a gallon of gasoline or repairing a flat tire. But Richmonders have created human settlement patterns that require more driving. Our sprawl is worse, and we have fewer mass transit options. Consequently, we devote a higher percentage of our incomes to transportation.

As Trip Pollard pointed out in “Healthy Community Choices for the Greater Richmond Region,” Richmonders developed more land between 1992 and 1997 than the far more populous Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads regions. As a consequence, Richmonders drive more than their counterparts in NoVa and Hampton Roads. Writes Pollard: “The people in the urbanized area [drove] an average of 28.2 miles per person per day in 2008, while people in Northern Virginia drove an average of 23.7 miles per day, and in Hampton Roads 24 miles.”

How much would a daily 4.5-mile-per-person differential between Richmond and Northern Virginia amount to, assuming the cost of transportation were the same in both regions ($0.55, according to the IRS mileage allowance)? Over the course of a year, Richmonders would spend $900 per person more on transportation than Northern Virginians! If the price of gasoline, repairs and insurance is cheaper in Richmond (which I’m guessing it is), the actual differential may be somewhat smaller. Yet the higher number of vehicle miles driven might well swamp those lower prices.

My purpose is not to disparage Kotkin’s larger point, which is that differences in regional cost of living matter. They do! Rather, I’m arguing that we need to be more careful in how we use the data and the conclusions we draw from it.