by James A. Bacon

Charles Marohn at Strong Towns has penned a fascinating piece comparing the financing of America’s railroad system in the 19th century with the construction of the nation’s Interstate highway system in the 20th. (Read the essay on the Smart Growth for Conservatives blog.) The railroads used a form of “value capture,” which worked extraordinarily well, while the Interstates used public funds, which, in hindsight, we can see hasn’t worked out so well.

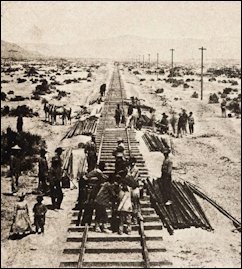

The federal government gave trans-continental railroads land along their routes. It was easy to give away — no one lived there (other than the Indians, and they didn’t count back then) so it had no value. Railroads created the value, and they sold off that value in the form of lots and parcels to pay off the railroad bonds they used to finance construction. By contrast, the federal government employed a motor fuels tax to finance construction of the Interstate system. While the tax at least was a rough user-pays system, it created a pool of money — Marohn calls it a “slush fund” — which politicians could allocate without regard to the economic viability of particular projects.

Marohn argues that the 20th-century transportation-funding system created two travesties. First, it severed the correlation between supply and demand.

We all subtly pay into a giant slush fund and then we all expect that slush fund to deliver on its promise and meet our insatiable demand. Members of the engineering profession have called taxpayers “whiners” for not wanting to pay more, but why would anyone pay more for something they don’t really value?

… People do value transportation, but at what price? Nobody really knows. Time and again we see that, when prices are not hidden in a slush fund but instead are paid by the user at the time of consumption, demand drops. For a government-led transportation system, a drop in demand is devastating. Put a toll on that road priced for current usage and fewer people will use it. The drop in demand forces an increase in the toll if the same revenue is to be sustained. An increase in the toll further depresses demand and on and on and on…

The second travesty is that the funding system eliminates valuable feedback regarding a project’s economic viability.

In the railroad era, private investment always led public investment. The railroads would construct the lines, build the towns and the town itself would be somewhat established before any public investments were made. … In the automobile era, the risk taking is reversed. For all but the most local of transportation improvements, governments front the investment capital and take the risk. …

What happened when the private railroad companies overbuilt their system? What happened when they got out in front of market and had too much supply without enough demand? They, of course, got the painful feedback of losing money and watching their assets drop in value. Sometimes entire companies went out of business.

What happens when the government, operating in the automobile era, overbuilds? What happens when we create so much supply, so many miles of roadway, that demand can’t possibly utilize it effectively? Well, the feedback isn’t quite so direct. Budgets start to be frayed. Obligations go unfulfilled. There isn’t enough return on these government investments and so there ultimately isn’t enough money to care for them. These things can be attributed to many causes, of course, most of which appeal to our psyche more than the idea that we’ve overbuilt.

Contrary to the protestations of the special pleaders, who maintain Virginia has an unfunded backlog of tens of billions of dollars of transportation needs and the nation has an underfunded backlog hundreds of billions, Marohn contends that the United States has built more road and highway infrastructure than it can effectively maintain.

Our solution, bizarrely, is to build more. So long as the government has the money to avoid the hardest decisions, any uncomfortable response – land use changes, shifting from automobile trips to walking or biking or modifications to the tax code, to name just three – will remain off the table, or at least relegated to the fringe. More money doesn’t solve any problems. It just forestalls the pain of transition, compounding the imbalances in the process.

Well done, Charles. Very well done.