by James C. Sherlock

I had never until now looked at college costs from the perspective of the new graduate, as opposed to his or her parents.

But it is fair to say that many look closely at their debt and their incomes after graduation and are taken aback, whether or not they borrow yet more to go on to graduate or professional schools.

So, I have examined available state data on student debt at graduation of the undergrads at Virginia’s public 4-year colleges and universities between 2016 and 2021.

If you expected the results that you will see here on their debts at graduation, you are much more informed that I was when I started.

Some are startling, at least to me.

There are many possible explanations; so many that I will not venture them with the exception of noting some actual room-and-board differences for commuter schools from students who live at home.

The rest represent some combination of parents’ ability to pay (and borrow) and schools’ abilities to reduce sticker prices with scholarships and other discounts.

None of that estimates the value of the degrees. None accounts for the debt of dropouts.

Background. The data I have curated and subjected to analysis came from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV) database EOM 04: Debt Profile: Student Loans by Race 5 Years, that offers known debt at graduation between 2016 and 2021.

Some of the data are clearly rounded estimates, some rather specific. The median was in the $26,000 range for the 60% of students who graduated with debt in 2021.

The data are broken out by race, labeled “majority students” and “students of color.”

Also of great interest would be EOM P01: Student Debt by Program Listing (what the students majored in), but those data are not available after 2011-12.

Student debt, of course, pays for more than tuition. The costs of room and board together can be major factors.

Some of Virginia’s public colleges and universities are more regional than others, enabling some students to live at home while attending, but we don’t know how many actually do that.

So, proximity should be a factor to reduce those students’ debts, but from the data it did not.

These data include transfers. But they do not include any debt that transfer students acquired while attending previous institutions outside Virginia. And it is noted in the data presentation that relatively few transfers from Virginia’s two-year colleges incur debt prior to transfer.

Finally, the burden of student debt in life is relative to post-graduate wages. If we had the data on debt by major by institution, families would have more insight when choosing a school and a major.

But I worked with what SCHEV has published, which I find significant despite those limitations.

Grads With the Least Debt, 2021.

Racial majority students graduated with the least debt (lowest to higher) from

- UVa Wise

- William and Mary

- UVa main campus

- Mary Washington.

Students of color graduated with the least debt from (lowest to higher)

- UVa main campus,

- William and Mary

- UVa Wise

- Mary Washington

Interestingly, only one of those, UVa Wise, is identifiable as a regional school.

Grads With the Most Debt, 2021.

Racial majority students graduated with the most debt from (highest to lower)

- Norfolk State

- Virginia State

- Christopher Newport

- VMI

Students of color graduated with the most debt from (higher to lower)

- Norfolk State

- Virginia State

- Radford

- Old Dominion

All of those but VMI and perhaps Radford can be described as primarily regional schools.

Fastest Growth in Graduating Majority Student Debt, 2016 – 2021

Old Dominion, by a very wide margin.

Fastest Growth in Graduating Student of Color Debt, 2016 – 2021.

- Old Dominion

- VMI

- UVa Wise

Bottom Line. This is a new way, at least for me, for looking at the costs of Virginia public colleges and universities.

One obvious question: why do not more students take advantage of the community college programs that guarantee admissions to state schools? I have no real data, though I am sure unawareness has something to do with it. SCHEV should examine ways to get the word out.

As for other changes, I encourage SCHEV to re-start collection and publication of debt by major by institution.

I also urge them to gather data on value to the degree to the extent possible by estimating wages in the first three years after graduation, by institution and by program, excluding those who went on to graduate school.

The additions of those data would be of immense help to students and parents picking an undergraduate school and for undergraduate students in picking a major.

Reducing that debt would be of help to students and the economy that bear far more student debt than is economically and socially healthy.

Finally, the federal government leaped headfirst into the retail banking business by grabbing control of student loans under the Obama administration and a Democratic Congress’s Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (HCERA). Four thousand colleges were forced to switch from private lenders to the government program.

What could go wrong?

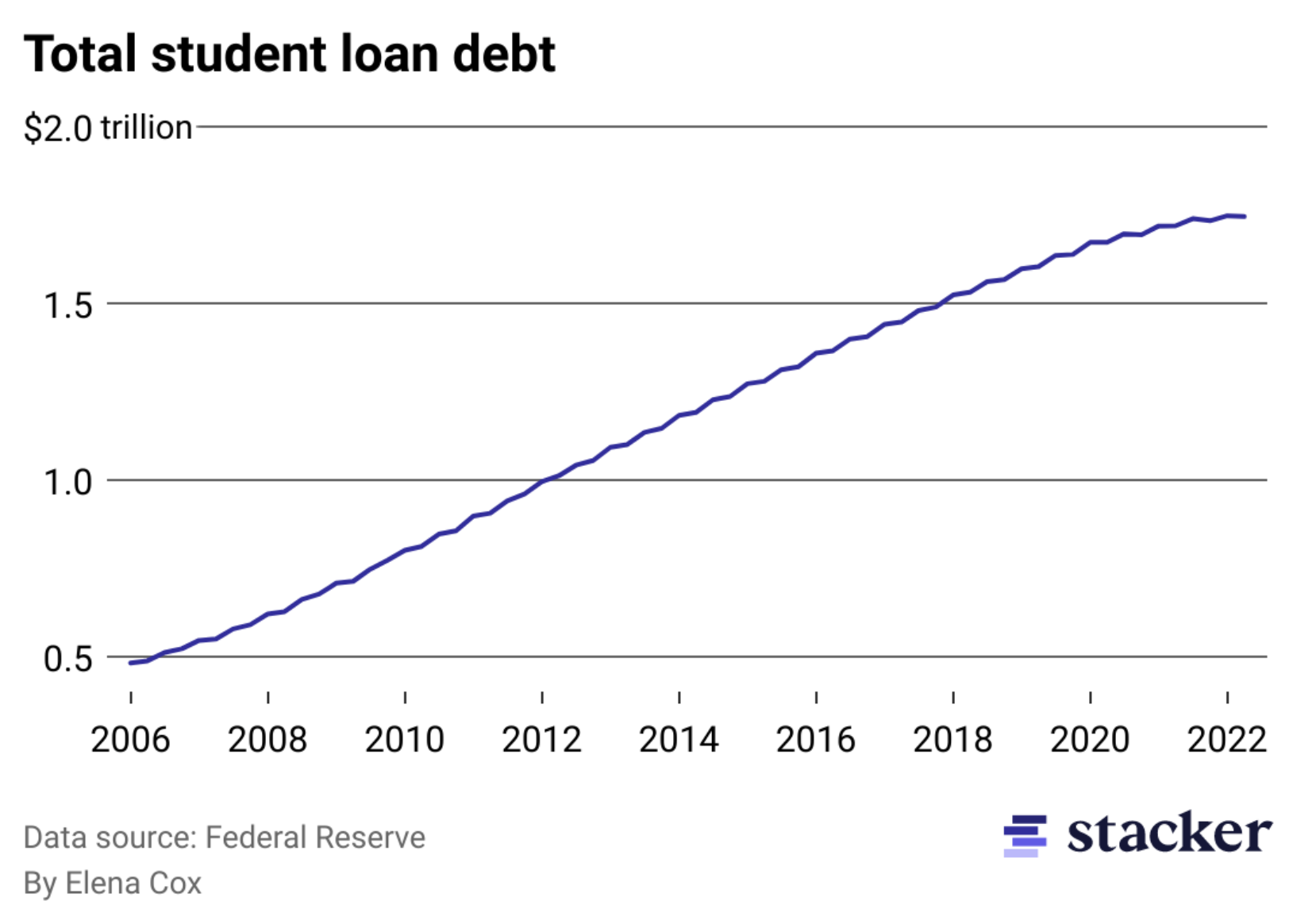

In 2010 the average annual tuition at four-year public colleges was just over $7,000 a year. It is now $23,250 annually. More than tripled in 13 years. Inflation in the total economy over that same period was 40%.

It thus did not slow the growth of student debt – quite the opposite. Look:

Now the government is unable, likely as a matter of constitutional law (14th Amendment) and certainly as a matter of basic fairness to Americans who do not attend college, to cancel the debt of college graduates whose career incomes will far exceed those of the majority of taxpayers.

For $2 trillion in student debt we can thank both our federal government and the institutions that leveraged the loan program to spend every penny regardless of value offered to students.