by James A. Bacon

After decades of losing jobs to the metropolitan periphery, the nation’s downtown employment centers have been recording faster job growth since the recession than areas located further from the city center, according to a new report, “Surging Center Job Growth,” by Joe Cortright, president and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis.

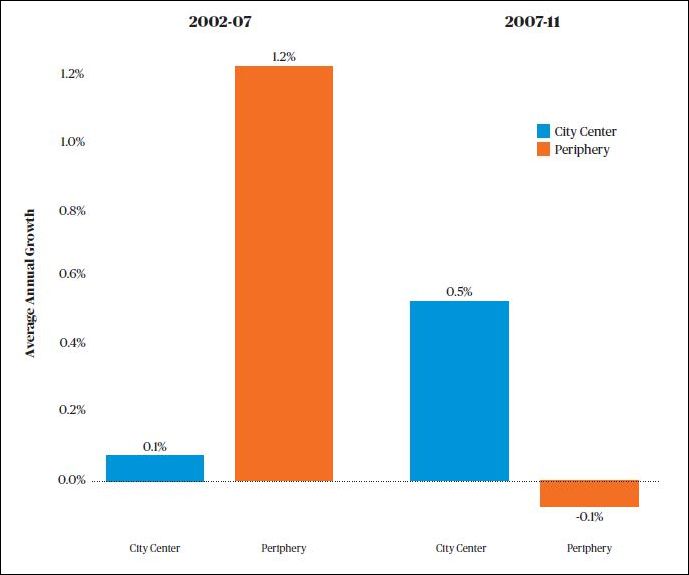

Cortright compared job growth between city centers (defined as within three miles of the center of a metropolitan region’s central business district) and outlying areas. During the go-go years of the 2000s-era real estate boom (2002-2007), the periphery enjoyed rapid job growth while city centers stagnated. Since the recession (2007-2011), city centers have gained jobs while the periphery has lost them.

Those numbers represent a composite of 41 of the nation’s largest metropolitan regions for which Cortright could find comparable data. The national trend does not apply to all metropolitan regions. Indeed in two of Virginia’s largest metro areas — Hampton Roads and Richmond — the periphery continued to out-perform the city centers.

What’s going on? The big-picture story is that the industry mix of the national economy is changing, and that shift increasingly favors central business districts.

In general, knowledge-oriented industries that require considerable face-to-face interaction are clustered in city centers, while goods producing and moving industries are more decentralized. Knowledge-oriented industries tend to use land much more intensively than goods producing and distribution centers.

The biggest construction declines occurred in the construction and manufacturing sectors, which tend to be located on the periphery. Those sectors have been slow to rebound during the recession, but if and when they do, Cortright said, the compositional disadvantage of the periphery might diminish. (By “compositional,” he means the advantage of disadvantage conferred by industry mix.) However, he argues that center cities will continue to enjoy generalized “competitive” advantage.

These factors — the growing preference of well-educated young adults for urban living, the shift of companies to city centers to tap this labor pool, the growing pull of the “consumer city,” the growth of “eds and meds,” the continuing relative decline of manufacturing and distribution, and the waning of major investments in new highway infrastructure — all give us reason to believe that the shift toward city center growth is not a temporary anomaly.

A closer look at Virginia metros. How do we explain the departure of Hampton Roads and Richmond from the larger, national trend? Remember that the “national” trend is derived from composite numbers that include a lot of variability. The trend does not apply equally everywhere.

Hampton Roads is a special case because its economy is so dominated by military spending, and military employment is concentrated in military bases. The military makes its decisions where to grow and contract based on different factors than the civilian economy.

As for Richmond, my sense is that downtown living and employment has surged since 2011, the most recent years cited by Cortright. The competitive advantages of central business districts apply to the Richmond region as well, and we’ll see the proof in more recent numbers. Another possibility is that the three-mile definition of “center city” does not fit Richmond, one of the smaller metros surveyed. The economic vitality of central districts like Shockoe Bottom and Manchester may be offset by declining employment in the 2- to 3-mile band, which are really aging suburbs.