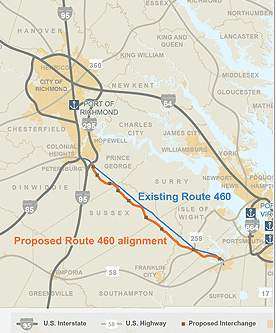

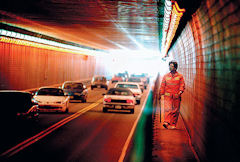

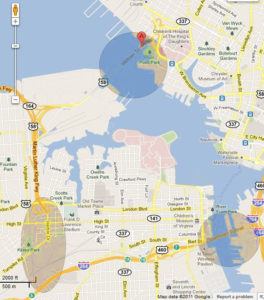

Norfolk view of the MidTown Tunnel. Photo credit: Virginia Department of Transportation

The $2.1 billion Midtown-Downtown Tunnel project will alleviate some of the worst traffic congestion in Hampton Roads. But the deal raises questions about transparency and accountability in Virginia’s public-private partnership law.

By James A. Bacon

Last week state officials and their private-sector partners took the podium at the Governor’s Transportation Conference in downtown Norfolk to describe the $2.1 billion Midtown-Downtown Tunnel project that had received the final go-ahead only days before. Chris Guthkelch, Elizabeth River Crossings (ERC) project director, described the engineering feat of moving 1.5 million cubic feet of sediment and depositing eleven massive sections of tube-tunnel, barged down from Baltimore, onto the river floor so they aligned perfectly. Dennis Heuer, Hampton Roads district engineer for the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), explained how upgrading the tunnels linking Norfolk and Portsmouth would reduce congestion, improve safety and boost regional productivity by between $174 million to $254 million annually.

But across the river in Portsmouth, details of the massive public-private partnership were not being received very well. Local officials expressed outrage at project financing that would impose tolls of $1.59 for cars during off-peak hours and considerably more for trucks and cars during peak hours. In future years, tolls will escalate at the annual rate of 3.5% or the Consumer Price Index, whichever is higher. Adding insult to injury, ERC will begin collecting tolls in 2012, five years before the project is even complete and the public experiences any benefit from it.

Addressing a crowd outside City Hall, Portsmouth Mayor Kenny Wright vowed to roll back the tolls. He called upon other cities in South Hampton Roads to join the effort. The state might have signed a comprehensive agreement, locking in the arrangement for 58 years, but Wright had only begun to fight. “This thing is far from over,” he said. “It is never too late, even with a signed contract, to negotiate how the tolls will be implemented.”

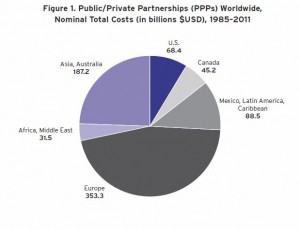

Public-private partnerships like the Midtown-Downtown Tunnel are incurring closer scrutiny now that the McDonnell administration has announced a series of new projects and promised a “pipeline” of other deals in 2012. As conventional sources of road-construction funds are eroded by inflation and mounting maintenance needs, McDonnell has turned to debt – his administration will borrow $4 billion for road construction – and P3s, as the public-private partnerships are known, to fill the gap. He is counting on the P3s to attract billions of dollars of toll-backed private investment to build projects the state never could afford otherwise.

In early December, the administration announced a series of major deals in quick succession. First, news broke of the $2.1 billion Midtown-Downtown Tunnel agreement. The next day, the governor announced an agreement in principle for a $940 million HOT lanes project on Interstate 95. The day after, word came that the state would invest $124 million to advance the Coalfields Expressway. Meanwhile, the newly formed Office of Transportation Public Private Partnerships (OTP3) is actively working on a deal to upgrade U.S. 460 between Petersburg and Suffolk to Interstate standards, a project that also will require significant state funding. The OTP3 is expected to release a list of other projects under consideration next month.

But even as the McDonnell administration charges ahead, making good on the governor’s campaign promise to “get Virginia moving,” critics are getting more vocal. While the critique of individual projects may differ, depending on details, several common themes are emerging:

- The P3 enabling legislation provides for little accountability. Citizens can’t see critical details of a transaction until the deal is already done, and there is no effective appeal.

- Concessions take the form of long-term agreements – 58 years in the case of the Midtown-Downtown Tunnel, 73 years for the I-95 HOT lanes – that effectively lock in transportation policy for decades to come.

- Some contracts contain clauses that either protect private-sector partners from competing projects or compensate them for lost revenue from future public investments, including mass transit service.

- P3 projects are suitable only for mega-projects that generate revenue from tolls or, possibly, special tax districts. By circumventing the usual process of review and approval by the Commonwealth Transportation Board for the expenditure of state money, projects jump to the head of the line and lay claim to scarce state dollars that could be more effectively spent elsewhere.

Transparency vs. Confidentiality

“I’m furious. The price of the tolls is too high and the governor signed this deal without consulting the mayors of the cities affected. We haven’t had a chance to weigh in and it’s not fair.”

— Portsmouth Mayor Kenny Wright

An inherent difficulty in crafting a public-private partnership law is the need to strike a balance between transparency and public involvement on the one hand and the confidentiality required to negotiate complex transactions on the other. McDonnell administration officials maintain that current law makes reasonable trade-offs.

“Our function is to deliver a completed project to the people of the commonwealth,” says Tony Kinn, the McDonnell administration’s point man on transportation public-private partnerships. “There are a lot of checks and balances.”

Those checks and balances can be seen in the process by which the Midtown-Downtown Tunnel reached final approval. VDOT solicited conceptual proposals in May 2008. When Elizabeth River Crossings submitted a proposal in September, VDOT promptly posted it for public inspection. An Independent Review Panel (IRP) held five meetings, including two public hearings, between February and June 2009 and recommended that the proposal be kicked back to VDOT for more work. During that evaluation phase, says Dwight L. Farmer, director of the Hampton Roads Metropolitan Planning Organization and member of the 12-person panel, the proposals were an “open book.”

In January 2010 VDOT and ERC executed an interim agreement to do more detailed work. Those deliberations were not open to the public. Still, as discussions progressed, VDOT released important details. In May 2010, then-acting VDOT Commissioner Gregory Whirley made a presentation to the Commonwealth Transportation Board that contained a project estimate of $1.9 billion. He also revealed that in the base case tolls would be $2.17 for cars with transponders in off-peak hours, but expressed the goal of buying down the tolls with subsidies to $1.50 per car in off-peak hours. Those numbers proved reasonably close to the figures contained in the final agreement executed a year-and-a-half later. However, many important elements, such as the length of the concession, the size of the state contribution and the toll price escalators had yet to be worked out.

In November 2010, VDOT also delivered a “Hampton Roads legislative briefing.” (Although there is a link on the VDOT website to the presentation, the document is not functioning at the moment. The link displays an error message.)

In January 2011, VDOT and ERC entered into “comprehensive agreement negotiations.” Those talks were highly confidential. A half-year later, in July 2011, however, discussions had progressed to the point where the new P3 czar, Tony Kinn, could describe “major business terms” to the Commonwealth Transportation Board. He provided information about toll rates, the toll escalation provision, the duration of the concession, the size of the state contribution and other key terms and conditions.

Throughout the process, VDOT posted studies, press releases, presentations and other documents on a Midtown-Downtown Tunnel website nested within the VDOT website. Content includes a project timeline, procurement and environmental schedules, 14 different technical studies, seven press releases, links to Virginian-Pilot articles, a newsletter (with only one edition), presentations made at four public meetings, minutes of the Independent Review Panel, a document library and answers to FAQs.

“The question is,” says Farmer, the MPO official, “when do you re-engage the public?” There is no easy answer. The process must respect the proprietary nature of the proposals that companies submit to VDOT, he says. Businesses can spend millions of dollars fleshing out their ideas. “You can’t reveal to your competitors what you’re thinking,” he says. Furthermore, negotiations can be protracted and contentious. It would be counter-productive to conduct delicate talks in the public arena.

Those are legitimate points, critics say. But the result is that public input effectively ceases after the Independent Review Panel. Although the CTB was informed of major developments as they played out, the statewide board has no authority to veto the project. Once McDonnell announced the comprehensive agreement, which runs 160 pages plus dozens of exhibits, the transaction was done. If someone has a problem with the contract, there is no appeal. Unless the state is willing to pay significant penalties, there is no opening the deal for renegotiation.

Experience has shown, says Trip Pollard, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, that the public-private partnership act “shifts power from the CTB and the legislature to VDOT.” The law, he contends, empowers the governor of Virginia to commit to long-term, multibillion-dollar contracts with minimal accountability or oversight. And that should worry people.

Tolls, Competition and Risk

A project like the Midtown-Downtown Tunnel will define Hampton Roads’ transportation future for the next six decades. No one disputes the desperate need for some kind of improvement. Roughly 38,000 vehicles per day pass through the narrow MidTown Tunnel and travelers routinely spend a half hour in bumper-to-bumper traffic during rush hour. Addressing the bottlenecks at the Midtown Tunnel, the Downtown Tunnel and Martin Luther King Boulevard, an inter-related set of projects, is critical, says Kinn. “The benefit of those projects is huge.” The state does not have the money. The public-private partnership gets the job done.

But does Elizabeth River Crossings offer the best long-term solution for the region?

That’s hard to say because the deal locks terms and conditions into place for 58 years. The project addresses real needs today, but no one knows what the state’s transportation needs will be 20 years from now, much less 40 or 60 years from now. No one knows what new technologies, economic trends or land use patterns might transform the transportation landscape. One could argue that a more flexible, more adaptable, arrangement would better serve the region in the future.

But not only will the deal lock in tolls for the next two or three generations, it will lock in escalating tolls. Hampton Roadsters will start out paying $1.59 for cars during off-peak hours. After years of escalating at a minimum rate of 3.5% annually, tolls will climb to $12 by 2075.

One can argue that the tolls aren’t so bad. VDOT estimates conservatively that the tolls will save drivers 15 minutes each way, a total of a half hour for a round trip. Assuming drivers value their time around $16 an hour on average (the figures used by the Texas Transportation Institute in its Urban Mobility Report) that represents a time savings valued at $8. Thus, $3.18 in tolls ($3.68 during rush hour) buys $8 in time savings. “As the economy improves,” says Kinn, “those terms will lessen.”

The contract also limits the state’s ability to make other improvements that might compete for, or siphon off, toll revenue. ERC can file for compensation if VDOT undertakes initiatives such as new bridges that divert traffic from the tunnels.

Kinn stresses that the contract does not contain a non-compete clause. The state can make any improvements it wants. However, he concedes, certain state actions could trigger “compensation events.” If after detailed study it can be shown that the state damaged ERC’s revenue stream, the concessionaire can submit to the state for compensation.

Another sticking point for regional Hampton Roads officials is the fact that the tolls won’t go just to pay for new construction but to address tens of millions of dollars in backlogged maintenance needs the state should have addressed years ago as well as maintenance going forward. In effect, Hampton Roads motorists will be paying for maintenance twice – once through the motor fuels tax, the revenue source that pays for maintenance across the state, and again through tolls.

That’s true, says Kinn, but VDOT is offsetting much of the double-taxation effect by contributing $362 million in state dollars to the project and buying down tolls.

Yet another objection is that the public has no way to judge whether VDOT drove a hard bargain. ERC will contribute $318 million in equity and borrow the rest. It is not known from public documents what profit margins ERC expects to earn. Is it the same rate as, say, a regulated electric utility? Or will ROI run higher on the grounds that the company is taking greater risks that traffic volumes and revenue might not materialize? There is no requirement in the Public Private Partnership Act for letting the public know.

Similar concerns apply to other public-private partnerships around the state.

In a draft white paper he has circulated, Pollard, the SELC attorney, raises other issues. P3s circumvent the environmental review process by advancing a project before alternatives have been evaluated, he says. Requirements for competitive bidding are inadequate, he adds: It’s too easy for the company proposing a project to establish a sole-source arrangement. Also, he says, projects can lead to more driving, sprawl and environmental damage. “Most PPTA projects built or proposed thus far,” he writes, “have been highway construction that will subsidize sprawl and increase motor vehicle dependence, destroying open space and increasing air and water pollution.”

Pollard argues that the Public Private Partnership Act needs to be amended. Projects should be limited to those already contained in state transportation plans, he says, not ideas dreamed up by a private-sector player looking for business. Among other changes he seeks: The public should be allowed to comment before a comprehensive agreement is signed, and the Commonwealth Transportation Board should be required to sign off.

“Experience with PPTA projects and proposals,” writes Pollard, “indicates that the statute is seriously flawed and raises significant doubts about how effectively it serves the public interest.”

=============

This article was made possible by a sponsorship of the Piedmont Environmental Council.