by James A. Bacon

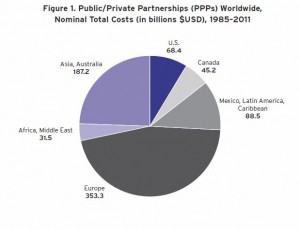

While Virginia’s Public Private Partnership Act may be experiencing growing pains as more projects see the light of day and invite public scrutiny (see “The Promise and Pitfalls of P3s“), there is little doubt that PPPs, or P3s, are the wave of the future. Indeed, the United States is something of a laggard in embracing this mechanism, which draws upon private-sector capital and management to build roads and other infrastructure. Europe has roughly five times the P3 investment as the U.S. Even Latin America has availed itself of this option more than the U.S. has.

However, P3s are getting more attention in the United States as resistance to higher taxes starves federal and state government of funds to ramp up more construction projects. Two very recent reports, one from the libertarian-leaning Reason Foundation and the other from the center-left Brookings Institution, are a sign that P3s are gaining legitimacy as a transportation-funding option.

Reasons’ “Risk and Rewards of Public-Private Partnerships” argues that the dynamics of P3s are well understood now that dozens have them have been implemented around the world. PPPs have five major advantages, writes author Baruch Feigenbaum. They (1) deliver needed transportation infrastructure sooner; (2) raise large new sources of capital; (3) shift risk from taxpayers to investors; (4) provide a business-like approach, (5) and enable innovation. “PPPs can be utilized in most types of projects and are most successful in states with strong enabling legislation.”

Imilia Istrate and Roberto Puentes at Brookings make another important point in their paper, “Moving Forward on Public Private Partnerships.” P3s are complex contracts, and negotiating them is not a task best left to amateurs and part-timers. The authors suggest that states develop “public private partnership units,” entities within the government that develop the technical and financial expertise to evaluate, negotiate and monitor P3 projects. It is encouraging to see that the paper specifically cites the the Office of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships in Virginia as one of only three examples of a genuine “public-private partnership unit” among the 50 states.

Virginians should take pride in the state’s recognition as a leader in implementing P3s, but the commonwealth’s enabling law still may need massaging. As I reported in “Promises and Pitfalls,” there is an inherent tension between inviting public input on the one hand and protecting the integrity of the very complex negotiations between the state and the private-sector concessionaire on the other. Citizens have a right to know how these mega-projects will affect them before deals are signed, and they should have some right of of appeal if the terms are onerous. Yet openness and transparency must be tempered by the reality that it would be impossible to ever complete a transaction if the public were involved at every turn and if key negotiating points were politicized.

A related problem is the project selection. The most fundamental question we need to ask ourselves is, “Should this project even be built in the first place?” It is of little comfort to know that a P3 can bring in a project cheaper and faster if we’re building the wrong road/bridge/rail project in the wrong location. In Virginia, the P3 projection circumvents the normal process for approving transportation projects. The Commonwealth Transportation Board is informed of major developments, but its consent is not required. The McDonnell administration is in the process of committing $1.5 billion in state funds to P3s and committing the state to 50- to 80-year concessions, all with toll-backed financing that will cost citizens billions of dollars more, and it does not appear to be accountable to anyone. No avenue exists for appealing unpopular projects.

I’m not singling out the McDonnell administration for blame here, by the way. The problems are inherent in the legislation, not the individuals in charge of carrying it out. And I’m not sure how we fix the problems. But they do need addressing.