Virginia universities shared business best practices today at Virginia Commonwealth University with the hope of finding ways to shave costs and improve the student experience.

George Mason University expects to save $3 million over the life of a five-year contract by outsourcing its printing operations to an outside vendor, defaulting to black-and-white print over color, and printing on both sides of the paper.

Universities make huge investments in parking lots and parking decks like this one at the University of Virginia. Today’s students are less car-centric than previous generations, and parking permit revenue has been falling. UVa has turned to metered parking to provide more convenience and recoup revenue.

The University of Virginia expects to generate $300,000 extra in parking revenue this year by shifting from the traditional arrangement, in which students purchase year-long parking passes for a space in a particular lot, to a system of metered parking that provides more flexibility as to where and when students park.

Virginia Commonwealth University doesn’t expect to save money from its Beyond Orientation program, an online orientation program for student’s parents and family members, but the university does hope to increase parental engagement in a low-cost way. When parents feel more comfortable navigating the university bureaucracy, they can provide more support for their kids, which bolsters the goal of graduating more students on time.

These were just three among the dozens of stories about higher-ed innovation highlighted at the “Partnering for Progress” event held today at VCU’s Siegel Center. Some stories reflect nothing more glamorous than the adoption of best practices that are common elsewhere. But some innovations are truly ground-breaking and have the potential to transform how higher-ed institutions function.

The event, itself a first-of-a-kind, featured an hour’s worth of speechifying and exhortations, plus two hours for schmoozing, visiting booths, listening to presentations, and swapping business cards. “Partnering for Progress” was backed by the Virginia Business Higher Education Council’s Growth4VA initiative, a public relations campaign driving home the message that Virginia’s colleges and universities make critical contributions to economic growth and prosperity. A recurring Growth4VA theme is that while state government needs to do more to support its public system of education, Virginia’s colleges and universities need to be more creative about controlling costs, reining in tuition increases, and helping students graduate with less debt.

There wasn’t time to visit every booth, but I had conversations with enough presenters to be persuaded that some very imaginative thinking is taking place in Virginia’s colleges and universities. It’s an open question whether these bright ideas get the funding and administrative support needed to transform the cost-encrusted higher-ed system. While some of the initiatives seem impressive, the thought occurred to me, why isn’t every institution adopting these changes? And what’s taking them so long?

Still, I came away convinced that there may be hope for Virginia’s higher education system. While higher-ed’s lobbyists and advocates may, for purposes of public consumption, be putting blaming runaway tuition on cutbacks in state support, administrators acknowledge the institutions themselves also bear some responsibility for holding down costs. Here follow some of the more promising programs I encountered in my perambulations through the Siegel Center.

Energy efficiency. Gains in energy efficiency had leveled off for several years at the College of William & Mary when Farley Hunter came on board to focus on utility management. Having worked in private-sector property management, he quickly spotted numerous opportunities to cut the university’s $7 million to $8 million in energy bills. W&M cobbled together a $140,000 revolving fund to invest in projects with at least a three-year payback, mostly in areas such as HVAC, ventilation and lighting. That’s a modest sum for a 200-building campus, concedes Hunter, but if he can demonstrate success, he expects the university to invest more.

Faculty productivity. University professors persevere through years-long Ph.D. programs to gain mastery of their subject matter. But unlike school teachers, they receive little instruction on how to teach. The University of Virginia Center for Teaching Excellence created the Course Design Institute to help professors organize and design better courses. Participants engage in a short but intensive exercise that begins with the question, “What do I want my students to know 3-5 years after the course is over?” The program uses proprietary software to build a syllabus and create “knowledge checks” that align teaching objectives with tests and assessments. About 500 UVa faculty members have gone through the program. Said program director Michael Palmer: “We created a revolution.”

Research productivity. University of Virginia researchers apply for roughly $1 billion in research grants in every year, and succeed in nailing down about $300 million worth. Only two years ago, however, the paper-based system for administering the research applications was extravagantly inefficient. It wasted space on literally hundreds of filing cabinets. Files were frequently misplaced (at an average estimated cost of $125 per file). The university even maintained a dedicated car and driver to carry papers from office to office around the grounds for needed signatures.

Ironically, UVa’s inefficiency turned out to be a blessing, said Vonda Durr, senior director of electronic research administration. Other institutions purchased multi-million-dollar software solutions to deal with the same paperwork issues, but many have them are dissatisfied and ready to scrap them. UVa learned from their mistakes and drew upon the university’s in-house IT staff to design a custom solution, starting with a portal for principal investigators, which makes contracts, account balances and other critical information accessible through one online location. The experience was so positive that the Office of Sponsored Programs added new capabilities such as electronic signatures, workflow tracking systems, and data visualization tools. Among other tangible benefits, the university has freed up space by getting rid of the filing cabinets, driven down printing costs, and saved an estimated $5 million in faculty and staff time.

Student retention. One third of the students entering Virginia Commonwealth University are considered “first generation” students — that is, they are the first members of the family to attend college. They are disproportionately poor and minority, and they have a harder time graduating from college. The graduation rate for first-time students is 78%, considerably lower than the 85% rate for all students, and GPAs tend to be lower. A high priority for VCU is improving the graduate rate for first-timers. The university’s You First program assembles a variety of orientation programs, faculty-led sessions, networking events, and support resources to ease the transition of first-timers into college life.

Virginia State University has a program with a similar purpose — helping students complete their college degree — that concentrates support services in a single location where students can access a wide variety of services. Students learn study skills and time management, get tutoring, receive counseling on which courses to take, and gain access to other support services. Every student is provided a mentor.

Radford University is adopting first-year living-learning communities organized around common interests such as the environment, the maker movement, biology, research, and the arts. Students living in the same residence halls take shared classes and engage in other activities together, building a sense of community and belonging. Participants have measurably higher retention rates and higher GPAs. Radford also uses data analytics to predict and improve student attrition. Remarkably, university ID swipes in dormitories and the fitness center is one of three factors with greatest predictive value. The data allows staff to reach out to students identified as being at risk of not returning to the university.

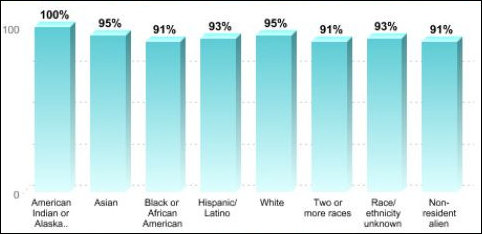

Virginia’s system of higher-education has the second highest six-year graduation rate in the country, second only to Utah. The payoff for students is huge — fewer drop out with big student debts they can’t repay. And the payoff is big for Virginia as well. When more students graduate, Virginia inches closer to its 20-year goal of becoming the best educated state in the country.

If Virginia ever develops a large fleet of offshore wind turbines, we may have a team of researchers led by the University of Virginia to thank.

If Virginia ever develops a large fleet of offshore wind turbines, we may have a team of researchers led by the University of Virginia to thank.

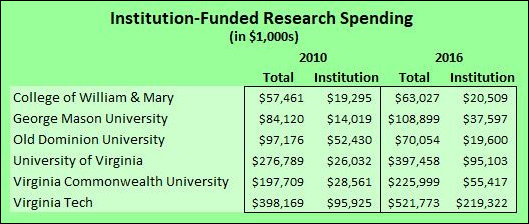

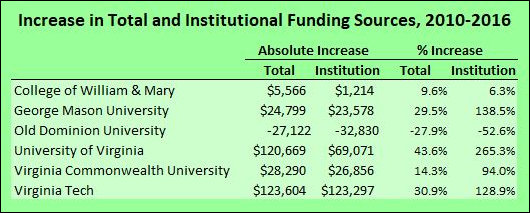

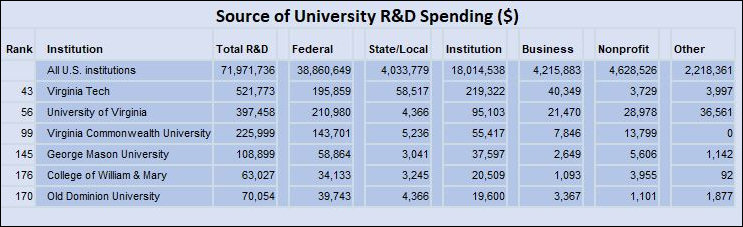

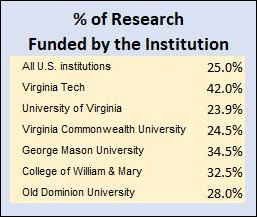

The average “institution” contribution for all U.S. universities is 25% of the total raised for research. Virginia Tech, George Mason University, the College of William & Mary (primarily the Virginia Institute of Marine Science), and Old Dominion University all exceeded the national average by wide margins. The University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University fell short of the national average by small margins. In other words, Reed’s critique does apply to Virginia higher-ed institutions.

The average “institution” contribution for all U.S. universities is 25% of the total raised for research. Virginia Tech, George Mason University, the College of William & Mary (primarily the Virginia Institute of Marine Science), and Old Dominion University all exceeded the national average by wide margins. The University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University fell short of the national average by small margins. In other words, Reed’s critique does apply to Virginia higher-ed institutions.