If Charlottesville and Albemarle County want millions of dollars for transportation improvements in the U.S. 29 corridor promised to them by the state, they will have to deliver something in return: Implement a credible plan to protect the highway from encroachment by future development.

That’s a message I got loud and clear this morning in an interview with Sean Connaughton. And it’s a message I should have absorbed when I reported a week ago on the discussion of a letter that the state transportation secretary had sent the Charlottesville-Albemarle Metropolitan Planning Organization regarding approval of transportation projects bundled with the Charlottesville Bypass.

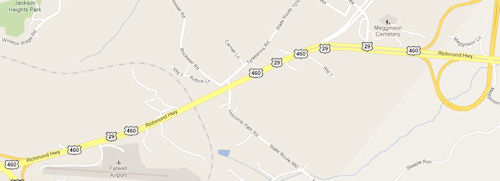

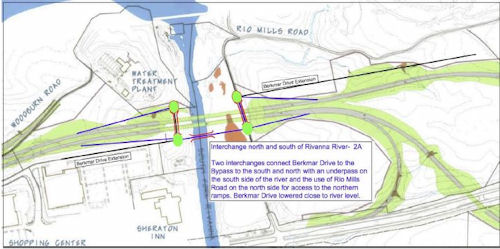

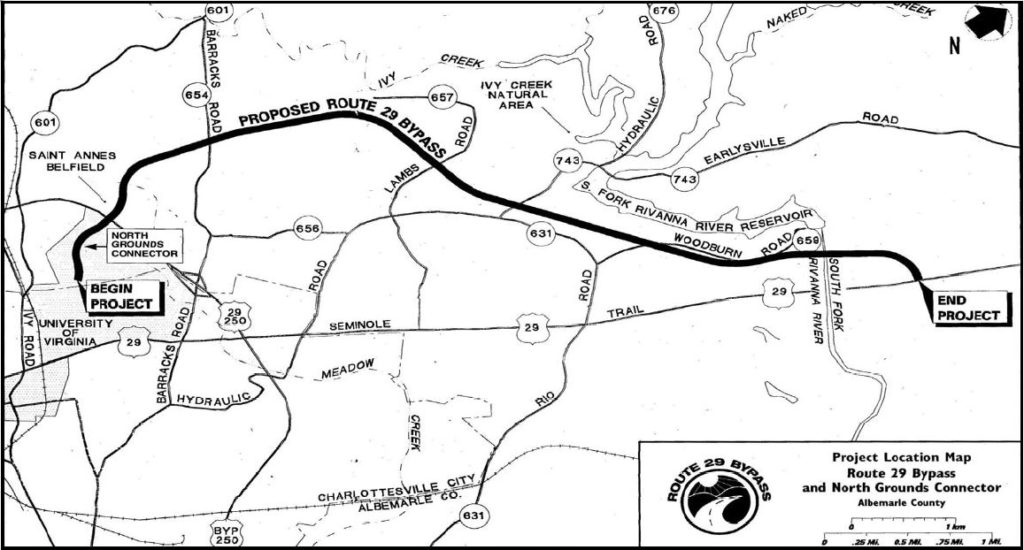

In that letter, Connaughton said he would ask the Commonwealth Transportation Board to fund or expedite four projects deemed crucial by Charlottesville and Albemarle County officials. These include three projects within the U.S. 29 corridor — the Berkmar extension, Hillsdale Drive and a new ramp at the intersection of U.S. 29 and U.S. 250 — as well as the Belmont Bridge in the city.

In my article, “Promises, Promises,” I focused on the issue debated by the MPO board members: What stock could local officials could put in Connaughton’s promises? Had he lived up to assurances he had given two MPO board meetings in a previous, private meeting? And was “recommending” something to the CTB as good as promising he would deliver?

As Connaughton pointed out to me this morning, I omitted mention of the last two paragraphs of his letter — the quid pro quo he was asking of local officials. Let me reproduce those paragraphs because they have significance far beyond Charlottesville and Albemarle County:

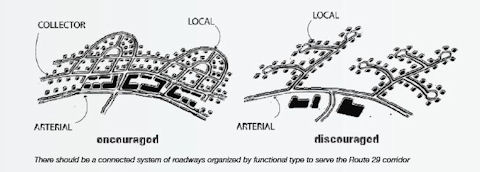

As you are aware, the CTB has identified Route 29 as one of eleven transportation corridors as Corridors of Statewide Significance (CoSS). The purpose of a CoSS designation is to provide a multimodal vision for the corridors to guide localities in their land use and transportation plans. Without guidance, local decisions can degrade a corridor’s ability to move people and goods, causing bottlenecks and problems that are costly to fix, and undermine economic and quality-of-life goals. As Virginia continues to grow, it must take steps now to ensure the right balance of development, transportation capacity, and natural resources. …

In consideration of the aforementioned transportation investments the Commonwealth is making in your MPO’s area of responsibility, it is our expectation that the MPO will commit to work with the CTB to develop and implement a comprehensive strategy that will protect your segment of the Route 29 Corridor from the types of encroachment that causes the bottlenecks and problems that we are currently planning to fix. We believe that the Albemarle-Charlottesville region has the opportunity to become a leader in this regard and, with your assistance, we look forward to making the CoSS initiative meaningful for localities and the traveling public.

Connaughton paraphrased the thrust of the letter this way: “We’re going to make you the test bed for corridors of statewide significance.” He wants to ensure that Charlottesville and Albemarle County avoid making the same mistakes again “so we don’t have to spend millions of dollars to build another bypass.”

Lesson to other jurisdictions: Connaughton is serious about implementing “access management” strategies in Virginia’s Corridors of Statewide Significance. (For more about access management, see “When Less is More.“) Charlottesville and Albemarle are first. You may be next.