by Matthew Hurt and Kathleen SmithReframing School Discipline

The Student Behavior and Administrative Response (SBAR) data collection was implemented in response to reframing school discipline from that of criminal, punishment, and exclusionary practices from 1991-2020 to that of restorative, intervention, and inclusionary practices in 2021 and beyond. The SBAR reports on behaviors that impede academic progress, behaviors related to school operations, relationship behaviors, behaviors that present a safety concern, behaviors that endanger self or others, and behaviors identified as persistently dangerous.

The SBAR records responses to discipline such as class removals, suspensions, expulsions with or without instructional services, and loss of privileges; behavioral interventions such as parents contacts, referrals, restorative practices; and instructional supports such as changes in placement, virtual programs, and support with and without face-to-face teacher contact.

The collection will always have inherent problems. Some data are clear: suspension or expulsion. Some data are not clear: support with or without face-to-face teacher contact. What if that contact was made by an administrator? Would removal for the last five minutes of class period be considered a removal? The reporting individual could inadvertently make the data very unreliable.

A cursory literature review demonstrated that “reframing discipline” occurred not only in Virginia, but throughout most educational institutions and juvenile justice organizations. Tight discipline policies in the late 1990s and early 2000s were replaced by less rigid or loose policies as early as 2010. After expulsions and suspensions catapulted, deterrent policies that used police, cameras, metal detectors, and locker searches were replaced by progressive policies that allow for a continuum of responses, prevention, intervention, supports, and consequences that foster positive behaviors.

Unintended Consequences of Both Tight and Loose Policies

Tight discipline policies do not allow for mitigation. The teacher uses minimal discretion for enforcement of rules. Breaking a rule, no matter the circumstance, is followed by a prescribed consequence. Loose discipline policies allow for more teacher and principal latitude over managing students. Loose discipline policies allow them to navigate the circumstance and use their professional judgment and expertise to decide on how much or how little consequence should be received.

Our efforts to address disproportionality through looser policies that allow more educator discretion and at the same time provide better reporting and hold schools accountable may have inadvertently caused additional problems.

In addition, given discretionary flexibility, schools and systems may be ignoring some behaviors to ensure the numbers are lower. This is normal organizational behavior, but as educators, we need to make sure it doesn’t contribute to additional negative behaviors by a student.

This is not like ignoring a two-year old’s tantrums so that he/she gets no attention and stops the behavior. It is more like ignoring a disruptive student who talks on his cell phone in math class, and who then decides it is okay to talk on the cell phone in all classes.

Further, Colorado & Janzen (2021) summed up another organizational tendency that resulted in disproportionality. Educators often “locate risk factors in socio-economic and cultural variables, wherein risk is seen as lying not in the behavior, but in the social position of those exhibiting it.” When risk is viewed as not lying in the behavior, but in cultural or socio-economic variables, expectations are lowered. When expectations are lowered, educators set the bar lower, and the achievement gap is more likely to widen. The same is true for discipline.

Disproportionality emphasis in the past two years may have inadvertently lowered expectations for some students’ behavior. Teachers have come to believe that a student’s behavior — for example, a secondary student’s use of an expletive when arguing with another student — is related to his/her culture differences, and therefore should be managed differently, in most cases, ignoring the problem. In actuality, the student is running roughshod over other students. This behavior would not be expected in any workplace.

In 2022, several teachers in Dr. Hurt’s consortium of 49 school divisions were interviewed. These teachers received high SOL scores for all students regardless of income, disability, or race. As expected, these teachers had limited, if any, discipline referrals. These teachers overwhelmingly stated that they did not have different expectations for any group of students, academically or behaviorally. Learning, they expressed, is not dependent on one’s zip code. These teachers expect students to follow rules. These teachers do not ignore the problem, but rather ensure that misbehavior does not persist. With one student, it may be a simple move or shake of the head by the teacher to let him/her know a problem exists. With another student it may be a simple reminder of the rules. The management of the problem has more to do with what works well for the student in terms of getting him/her to desist in the behavior.

For example, Dr. Smith used simple phrases to remind students of the consequence and cue him/her that the behavior might be disrupting. For example, she would position herself close enough for the student to hear her quietly say “seven digits” which meant, “careful, there may be a telephone call to mom tonight.” For another student, she would set up a system in which a piece of masking tape was placed on his/her desk. The student knew in advance that when there were five “x’s” on the tape, a phone call would be made to mom.

Virginia’s Tiered System of Support

Virginia Tiered Systems of Supports (VTSS) is a data-informed, decision-making framework for establishing the social culture and academic and behavioral supports needed for the school to be an effective learning environment (for academics, behavior, and social-emotional well-being) for all students. Established in 2014, VTSS is an approach that allows divisions and schools to provide targeted, evidence-based interventions to meet the needs of their students. This is done through a clearly defined process that is implemented by all stakeholders within the school and/or division. This approach is process- driven and is included herein as the approach recommended by the Virginia Department of Education. The VDOE has engaged with Virginia Commonwealth University to provide ongoing training and technical assistance.

VTSS reports a track record of positive results for participating schools. Currently, 58 Virginia school divisions are participating in VTSS. Each year, schools in participating divisions submit fidelity of implementation and student outcome data to the Virginia Department of Education.

The following data are based on VTSS Cohort 1-2 schools that are implementing VTSS and have submitted outcome summary data for five consecutive years (n=38). Highlights of VTSS’s positive outcomes from the VCU website include the following:

• 38 percent decrease among general education students and a 15 percent decrease among special education students in the average number of office discipline referrals from End-of-Year (EOY) 2015 to EOY 2019;

• 39 percent decrease among general education students and a 21 percent decrease among special education students in the average number of out-of-school suspensions from EOY 2015 to EOY 2019; and,

• 39 percent decrease among general education students and a 19 percent decrease among special education students in the average number of in-school suspensions from EOY 2015 to EOY 2019.

VCU and VDOE also provided this statement regarding SOL data for VTSS schools in the 2019 Annual Report:

Seventy-four percent, 66 percent, and 68 percent of state-reported VTSS 1-2 schools remained consistent or improved English Reading SOL pass rates from 2013-14 to 2018-19 for all students, African American students, and students with disabilities, respectively. Eighty-seven percent, 87 percent, and 79 percent of state-reported VTSS 1-2 schools remained consistent or improved Mathematics SOL pass rates from 2013-14 to 2018-19 for all students, African American students, and students with disabilities, respectively.

It is very difficult to objectively evaluate the effectiveness of VTSS. A lot of factors influence discipline reporting and outcomes in schools. As discussed earlier, if student needs are met at a greater rate, the discipline outcomes in a school will improve. However, there have been instances in which schools have improved discipline statistics by ignoring behaviors that would have been addressed in the past. When this happens, the learning environment suffers, but things look better on paper.

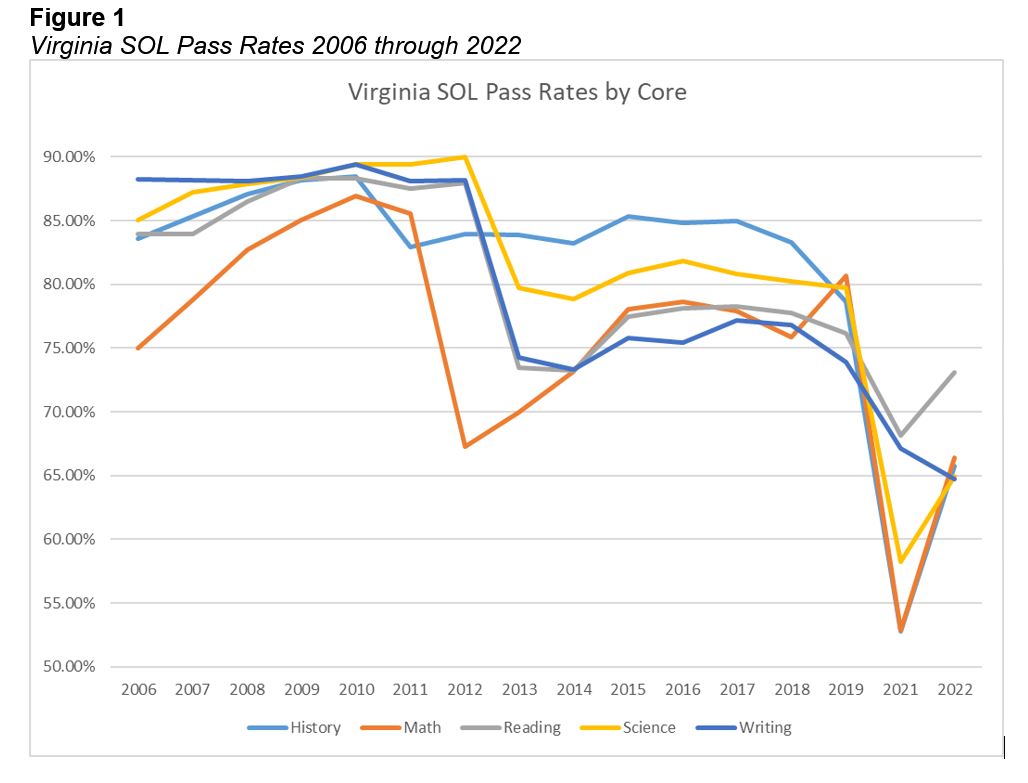

The second problem is the student achievement metrics used to support academic outcomes in those schools and divisions that employed VTSS do not indicate any improvement in student outcomes relative to the other schools and divisions in the state. A variety of occurrences have taken place over the years significantly influencing SOL pass rates that have had nothing to do with teaching and learning. When a more rigorous SOL test is administered, scores drop across the state. When the Board of Education decides to lower cut scores, pass rates increase significantly.

Over the timeframes the VTSS reports academic outcomes (2014 through 2019), the SOL pass rates for the majority of school divisions and the entire state improved. Therefore, the claim that the implementation of VTSS had any positive bearing on student academic outcomes isn’t necessarily supported.

Commentary provided here is not intended to imply that the VTSS process is not worthy. However, there have been no objective data supplied that we can find which effectively evaluates the efficacy of this process.

Safe Schools vs Safe and Orderly Schools

The JLARC report brought attention to how school discipline and the conditions related to the pandemic have contributed to low teacher morale and teacher retention issues. Nearly three-fourths of teachers reported that morale is lower since the pandemic. About two-thirds reported they are less satisfied with the job. Of the teachers who indicated they are likely to leave by the end of the 2022–23 school year, a majority cited these effects of the pandemic as a contributing factor. Fifty-six percent of teachers cited a more challenging student population, including behavior issues as a very serious issue. Forty-seven percent cited a lack of respect from parents and the public.

A school can be structurally safe and have a school safety plan that meets all requirements. Dr. Smith served as a member of a special team put together by an-out-of-state Public State Superintendent for the purposes of finding out why a certain school appeared to be in chaos. The team found that the school met all safety requirements but bullying took place in every corner. Teachers and kids were in fear. Teachers and students reported they couldn’t give a description of the principal. They had never seen her. She had been there four months, the previous principal less than a year. Teachers turned a blind eye to bullying to survive. They were afraid to say or do something that would make the bullies worse or be reported to the central office for having poor classroom management. Only about 2 percent of the students were bullies, and the other 98 percent couldn’t escape the boundaries of the school. They were trapped. Day after day, students were victimized, and nothing was done to the perpetrators. (As requested by the Public State Superintendent, the team reported its findings to that office and there were consequential and severe actions.)

It is important to define a safe and orderly school and not just a safe school. What would be some of the measures and would these measures inadvertently create more problems for the same reasons that highlighting disproportionality may have caused some ignoring behaviors?

Further Discussion Needed

The current General Assembly, as always, considers several bills regarding discipline. Do discipline policies need to be tight with prescribed actions for administrators to take without any regard to the reality of the situation? Or do discipline policies need to allow administrators to consider the situation at the risk of ignoring behaviors that do not need to be ignored? Do we trust our administrators and processes to make fair and just decisions regarding discipline? What checks and balances are there in place to ensure proper justice is served? Are the data collected useful?

Dr. Smith has always been apprehensive of the words “improving or staying the course.” What does it really tell us? A quantified indicator is either present or not. Also, less is better. Too many indicators are confusing. What constitutes a safe and orderly school? Who should define a safe and orderly school? Should the definition be the same in every community? How should one show improvement? Is a one percent change over last year an indicator of improvement?

Suppose you had to vote on legislation that would require any 9-12 grade student who had more than three unexcused absences to attend a five-hour seminar on the importance of attending school. What would be the unintended consequences of this bill? What impact would this have on the family? The school? The staff? What about funding this requirement?

We welcome your input.

Matthew Hurt is director of the Comprehensive Instructional Program, a coalition of non-metropolitan school districts. Dr. Kathleen M. Smith has been an educator since 1975. She has served as Regional Director for the Mid-Atlantic States for Advanced l Measured Progress and Director of the Office of School Improvement with the Virginia Department of Education.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.