by James C. SherlockHere is the information from a slide briefing to the Loudon County school board on February 6, 2013.

by James C. SherlockHere is the information from a slide briefing to the Loudon County school board on February 6, 2013.

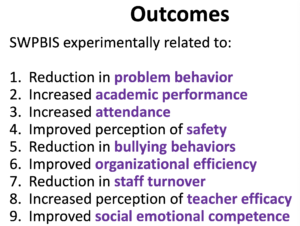

“Experimentally.”

The slide itself was actually produced in 2008 by pbis.org. It seems like a bad joke now, but that was how it was presented.

Not a word about race there, but there surely is in a presentation linked by that organization now. Risk index and risk ratios? With cartoon figures of Black children? Seriously?

Did I mention that Newport News Public Schools is rated fluent in PBIS by the state ed school consortium that trains and rates PBIS schools? They probably would take issue with all of those promises.

As would most of the working staff of schools across Virginia that use PBIS.

So how did we get here?

The measures of the success or failure of any intervention designed to improve discipline are the outcomes of that intervention.

Outcomes should be described in terms of whether student discipline or academics or both show improvements (or regressions) compared both

- in relative terms to past performance; and

- to alternative interventions.

School-wide interventions require a lot of training and great efforts to implement, so those chosen need to work or be discarded.

We spent the last part of this series discussing the fact that the federal Department of Education has published strong evidence in scientifically valid studies that the intervention framework Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) has not resulted in positive improvements.

But let’s move on.

How is PBIS working out at the level of individual school divisions and schools in Virginia?

I have found it surprisingly and maddeningly difficult to get a direct answer from the school division and school board web sites. Depending upon the school division, so will you.

But the entire positive school-wide discipline movement, so promising at first, took a hard left turn in Virginia in the second decade of this century.

PBIS as currently practiced is now focused on establishing racial and ethnic proportionality of discipline. It changes the rules, redefines offenses and their consequences and punishes those who do not minimize racial disparities in reporting of discipline statistics.

Preventing bad behavior is not nearly on that level as an agenda.

And they actually think, or say they think, that they are helping teachers and kids that way.

Let’s look.

Origins of Positive Schoolwide Discipline in Virginia Schools. In 2009, with Tim Kaine as Governor, the Superintendent of Public Instruction published the fourth edition of An Introduction to Effective Schoolwide Discipline in Virginia (Effective Discipline).

It was subtitled “A Statewide Initiative to Support Positive Academic and Behavioral Outcomes for All Students.” It discussed improving the behaviors of all students.

Students with disabilities were singled out, but not by race.

It focused on things like

- affording teachers more time for instruction;

- improved academic achievement through reduced disruptions;

- reducing negative consequences for students that led to more antisocial acts and poor academic performance;

- scientifically based interventions;

- advising school personnel to “(a) look for ways to alter aspects of the social as well as instructional environment; (b) explicitly teach students what is expected of them; (c) acknowledge appropriate behavior in ways that are valued by students; and (d) explicitly provide faculty and staff with staff development on behavioral interventions and effective strategies to address behavioral problems;

- at the student level, school personnel were said to rely on individual interventions based on formal Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA).

Effective Discipline

focused on individual schools.

After education personnel identify their expectations, all students are taught directly and systematically (a) when to engage in the behavior and (b) how to perform the behavior. Faculty members make extensive use of modeling and role-play activities to minimize any confusion or misunderstanding regarding specific expectations. When teaching the student classroom expectations, teachers establish clear objectives that are specific and measurable. Students are given multiple opportunities to practice the expectations and to receive positive reinforcement for doing so. Later, after students learn the expectations, teachers routinely introduce a scaled down version of the original instruction to ensure that students maintain the behaviors.

(As an aside, that is pretty much how Success Academies approach discipline training for their “scholars.” Before they teach their kids anything else.)

Data were to be collected, responses tiered, and progress monitored. FBA’s were to be given to the most troubled kids in Tier 3. Positive interventions and special supports were offered to those kids.

I could not find the word “race” in the entire document. Might be there, but if so I missed it.

The left turn. But since at least 2013, the introduction of PBIS in many school divisions that employ it has followed a very different, race-centric strategy.

Those divisions developed heightened awareness of clear mathematical disparities in suspensions, expulsions and arrests of minority students and students with disabilities, and the negative effects of those disparities.

That was a real problem that needed to be addressed and school boards addressed it in different ways.

Without question, all of them needed to adopt intervention strategies to improve behavior of all of their students to improve the school climate for learning.

Statewide Initiative had offered a prescription for that well before 2010.

But many school divisions were pitched PBIS as the best solution, whose supporters then and now blame the disparities on structural racism, not on broader economic and social disparities and correctable bad behavior. Especially not correctable behavior.

But that was not the way it was sold. A typical PBIS adoption approach was used in Loudoun County in 2013:

- removal of predetermined consequences (so-called zero tolerance) for infractions

- replacing zero tolerance with PBIS and its graduated discipline practices and emphasizing context and intent as factors to be assessed rather than just the occurrence of the offense;

- those practices were designed to move away from out-of-school suspensions and expulsions and replace them with in-school suspensions, restorative practices, and Collaborative Problem Solving;

- specific procedures for discipline of students with disabilities (SWDs);

- a revised discipline appeal process;

- aggressive collection and reporting of relevant data broken down by race and ethnicity;

- a new committee of the school board to oversee PBIS adoption and functioning; and

- explicit strategies in school improvement plans to reduce over- representations of minority and disabled students among students who are assigned a disciplinary consequence.

However race got inserted and the transition happened, PBIS has become, in some schools and certainly at many division levels, a numbers game focused on the relative/disproportionate discipline of minorities and SWDs rather than on the quality of the actual school environment.

Proven alternatives identified by IES described in yesterday’s article are not considered.

Reports to higher authorities are presented by race and disability status.

Out-of-class and certainly out-of-school punishments are reported and considered individual failures of school personnel, not of the system or individual students.

Exceeding racial, ethnic and SWD disproportionality limits for reported incidents and suspension/expulsions is considered the failure of individual principals and teachers. Evaluations reflect that as failure. Re-training is mandated. Promotions are unlikely. Repetition can be cause for dismissal.

The folks in the trenches — principals, APs, special staff and teachers have gotten that message.

Some rise above it to do the right thing the right way; many don’t.

When seeing themselves and their peers assaulted and shot in pursuit of a dangerously failed agenda, many just leave.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.