by James A. Bacon

Here we go one more time… Does cultural background influence the likelihood of Virginia students passing the Standards of Learning tests, or do disparities in results between racial/ethnic groups reflect only the disparity in resources allocated to different schools?

Over the past week, I have been arguing that cultural background is one critical differentiator, not the dominant differentiator — poverty (or economic disadvantage) accounts for roughly 57% of the variation — but it is nonetheless an important one. I allow for the possibility that some schools are better run than others, some teachers better than others, and that differences in resources may account for some variation. But culture is a significant factor, as can plainly be seen in the superior academic performance of Asians, both economically advantaged and disadvantaged, across the board.

But some readers doggedly refuse to acknowledge that culture plays any meaningful role. Among the most tenacious is our old friend Larry Gross, who asks a valid question that needs to be addressed. Pick the same school division, say Fairfax County. Then pick different schools within that division. The SOL pass rate for black children varies substantially. As he commented in my last post, “The SOL Debate: Bringing Asians into the Equation,” pass rates for blacks for 3rd grade reading in some of the Fairfax Elementary schools are all over the map:

Annadale Terrace 36%

Bren Mar Park 62%

Bull Run 71%

Brush Hill 47%

Rolling Valley 50%

Saratoga 46%

“How,” he asks, “is this explained by culture?”

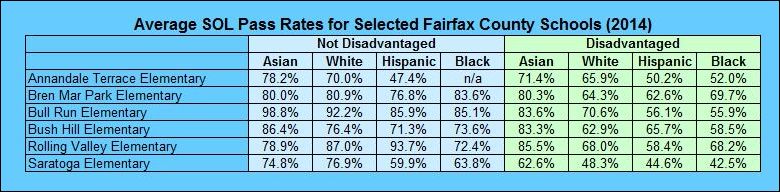

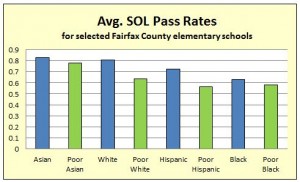

Let’s take a closer look. Here are the average SOL pass rates for all subjects at all six schools — hand picked by Larry to illustrate his point — broken down by race/ethnicity and by economic disadvantage, with the same information presented in chart form below. (Note: the DOE data did not include some scores for certain subjects for certain racial/ethnic groups. I have made the necessary adjustments.)

As expected, economic disadvantage plays a major role. For every ethnic/racial group, economically disadvantaged students showed a lower SOL pass rate than those not disadvantaged.

As expected, economic disadvantage plays a major role. For every ethnic/racial group, economically disadvantaged students showed a lower SOL pass rate than those not disadvantaged.

However, differences remain. Same school division, same schools, same economic classification…. We see the same pattern repeated over and over. Asians score highest, whites not quite as high, Hispanics lower, and blacks lower. As discussed in other blog posts, the difference between whites and Hispanics largely disappears when adjusted for English proficiency. But Asians consistently score higher than other races, and blacks usually, although not always, score lower.

Does that settle the issue? Probably not. Here’s what we don’t know. Are some of the selected six schools better run, do they have more experienced teachers, or do they have more resources, any of which my skew results between schools? Those factors undoubtedly come into play — we just can’t isolate those variables from this data.

Am I saying that culture accounts for all the variation between racial/ethnic performance in those six schools? Of course not. Clearly, even after adjusting for economic disadvantage and ethnic background, some variability remains. Equally clearly, there is a lot of variability within ethnic/racial groups. Some Asian kids just can’t get their act together. Some African-American kids are academic superstars.

But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that culture explains some of the overall superior academic performance of Asian kids. Such a conclusion is not terribly controversial. We see the high performance of Asians back in the home countries of China, Korea and Japan. We’ve all heard of “Tiger moms.” We observe that Asians are not nearly as prominent on athletic teams but way over-represented when academic awards are handed out. We can admit the obvious because it does not upset deeply held political views on race and race relations. But as soon as we begin talking about the differences between whites and blacks, talk of culture becomes incredibly touchy. Indeed, a lot of people, suspecting racist motives, find it offensive when conservative white people bring the subject up.

But the idea that cultural attitudes affect educational outcomes is not terribly controversial in the black community. Bill Cosby famously highlighted the issue. Just yesterday Michelle Obama stressed the importance of education to an inner-city Atlanta school:

Do you hear what I’m telling you? Because I’m giving you some insights that a lot of rich kids all over the country — they know this stuff, and I want you to know it, too. Because you have got to go and get your education. You’ve got to.

Even Ta-Nehisi Coates, a leftist black writer, says the idea is widely accepted. In The Atlantic, he writes:

The idea that poor people living in the inner city, and particularly black men, are “not holding up their end of the deal” as Cosby put it, is not terribly original or even, these days, right-wing. From the president on down there is an accepted belief in America—black and white—that African-American people, and African-American men, in particular, are lacking in the virtues in family, hard work, and citizenship. …

[Paul] Ryan’s point—that the a pathological culture has taken root among an alarming portion of black people—is basically accepted by many progressives today. And it’s been accepted for a long time.

The serious debate isn’t over whether cultural differences are important, it’s why the differences exist. Coates emphasizes blacks’ history of slavery, Jim Crow and ongoing racism. Conservatives emphasize the debilitating aspects of the welfare state. Leftists don’t want to “let whites off the hook” for their racism. Conservative whites are tired of being blamed for all problems in the black community. It’s fine to have the debate. What’s not OK is to pretend that contemporary African-American culture, especially among the poor — arising, as it does, from a history of slavery, Jim Crow, racism, the welfare state, an assertion of cultural identity, a rejection of the culture of white oppressors, whatever — has no effect on academic performance. To acknowledge that fact does not negate the fight for equal educational resources. What it suggests is that for African-Americans to enjoy economic equality in the United States, it is not sufficient only to reallocate resources among schools, it is necessary also for African-Americans to place a higher priority on educational achievement.

For that matter, whites need to hammer home the same message to their own children. The superior academic performance of Asians should bother them. Whites don’t emphasize educational achievement enough either. The difference is that most whites fret about the gap with Asians and don’t make excuses for it. They know Asian kids work harder, they respect the Asians for it, and they wonder, how do we get our kids to spend less time playing video games and more time cracking their books?

At the end of the day, it’s up to our public schools to give every kid an equal chance to succeed academically and reap the rewards that come from that achievement. But it’s also up to families, of whatever race or ethnicity, to make sure their kids take full advantage of the opportunities presented them.