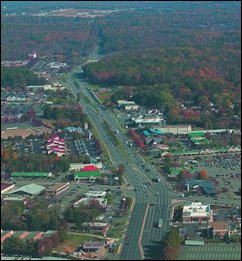

U.S. 29 north of Charlottesville. Once upon a time, this was a highway. (Photo credit: C-ville.com.)

Over on Strong Towns Chuck Marohn is running a five-part series on how to restructure transportation policy in his home state of Minnesota. Despite a different state/local government structure and different spheres of authority for the two states’ transportation departments, many of his proposals carry over to Virginia. In today’s missive, he tackles three issues that seem particularly pertinent to the Old Dominion.

Interstate highways. Marohn outlines his idea of a “base” Interstate system, which performs the function for which it was originally designed of connecting major cities, or centers of economic activity. A base of two lanes (each direction) should be maintained by federal gas-tax dollars for the purpose of “making high speed connections between productive places.” The purpose of the Interstate system is to move people, goods and materials as quickly and efficiently as possible between economic centers, not moving them as fast as possible within economic centers.

Marohn does not say so explicitly but his commentary implies it: Any lanes built beyond that two-lane base are required for local or regional connectivity, hence, should be the responsibility of state, regional or local authorities, not the federal government. He then suggests that these lanes be subject to congestion pricing. “The revenue from this fee will … be sequestered to fund maintenance of the extra capacity and, where needed, future expansion of the corridor (by whatever mode is most feasible).”

Interstate exchanges. Interstate exchanges should be built and paid for with federal dollars at the rate of no more than one interchange per six miles outside a municipality. Their maintenance should be paid for with the federal gas tax. If someone wants to build additional interchanges, construction should be financed by means of “value capture,” a tax assessment on property owners whose values would rise as a result of the improvement. If value-capture financing cannot support the cost of constructing the interchange, there is no economic justification for it, and building it represents nothing but a wealth transfer from the general public to private property owners.

State highways. Marohn suggests that federal funds should be applied to maintaining the equivalent of one lane (each way) for state highways, with additional lanes to be maintained and expanded as needed by means of congestion charges. That’s an elegant idea in theory but I worry about its applicability in the real world. Not only are there costs associated with administering congestion charges but it would be prohibitively expensive to segregate individual lanes on state highways, especially where those highways have been co-opted by urban transportation systems with lots of traffic lights, cut-throughs, driveways and entry points. I’ll set that aside as a utopian ideal for the moment to focus on what I think is an economically feasible idea.

Under Marohn’s scheme, any private access to a state highway where the speed limit is set at 30 m.p.h. or greater should be subject to an annual access fee.

The fee will be based on a ratio of the traffic on the highway versus the traffic accessing the highway, using methodology currently applied in signal placing and benefit/cost analysis. Under such a system, a farmer with a driveway on a remote state highway might pay $25 per year since the impact of a single home on a low volume roadway would be minimal. A strip mall on a congested corridor may pay thousands (or more) to offset the cost of slowing traffic on the highway. The access fee is compensation to the general taxpayer for degradation of the highway’s capacity, which the general taxpayer funded.

That seems eminently doable. I would argue that existing access points should be grand-fathered, otherwise the political hue and cry would be so deafening that it would be impossible to pass legislation to put the idea into effect. But at the very least, Virginia should begin charging for new access to state highways.

Marohn proposes a more complicated mechanism for urbanized areas where highways have been compromised by a profusion of intersecting streets, traffic signals, cut-throughs, curb-cuts and the like.

Within cities, in areas where the speed limit is less than 30 mph, all properties within half a mile of the highway (measured perpendicularly) shall have a highway surcharge on their property tax. The surcharge will be based on the value of the land (higher valued land will pay more, note it is the land only and not the total improved property value) and is meant to pay for (a) the added costs of constructing and maintaining an urban highway, and (b) compensation to the general taxpayer (who funded the system) for degradation to the highway’s capacity. It should likewise be sequestered for this purpose.

That’s an interesting idea but it raises a lot of questions, not the least of which is, why charge property owners as much as a half-mile from the road as opposed to dunning those with curb-cuts emptying directly onto the highway? Still, it’s a good place to start the conversation.

I would suggest one modification: The revenues raised from an access charge should go into a fund that is used to purchase the rights to grandfathered access points. The goal over the next five decades or so would be to convert state highways back to the unencumbered highways they were a half-century ago.

Finally, I would argue that, here in Virginia, it would be politically impossible to implement such an overhaul statewide. But it might be feasible to introduce the idea by means of pilot projects. The perfect place to begin field-testing the idea would be U.S. 29, with a focus on the congested area north of Charlottesville. The McAuliffe administration should pull the plug on the proposed Charlottesville Bypass and use the funds to implement the Places29 plan. An adjunct to that plan would be an access management plan to protect whatever integrity is left to the U.S. 29 corridor up and down its entire Virginia length. Using U.S. 29 as a test bed to iron out the wrinkles of the access-management program would pave the way for protecting the state’s other highway corridors.