by James A. Bacon

The federal government plays a much bigger role in shaping the United States economy than is evident in its taxing and spending policies. Uncle Sam funnels credit to favored constituencies through subsidized credit programs like TIFIA transportation loans and the Import-Export bank as well as by protecting lenders from losses due to a borrower’s default. Members of Congress are exercised, as well they ought to be, by the dispensing of subsidized credits to corporate interests. But loan guarantees have a far bigger impact — and expose the federal government, and the U.S. economy — to far greater risk.

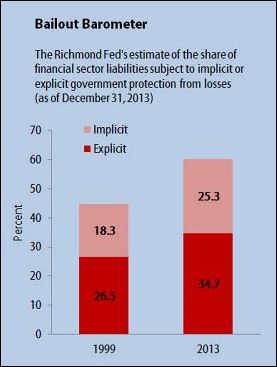

Sixty percent of the U.S. financial system’s loans are explicitly or implicitly backed by the federal government, the Federal Reserve Board of Richmond has found in its updated Bailout Barometer. That’s up from roughly 45% as recently as 1999.

The capitalist financial system is inherently prone to booms and busts. Busts lead to corporate failures, and big corporate failures can trigger panics, in which even financially sound firms get caught in the undertow. The U.S. has sought to alleviate this pain by providing loan guarantees. Some guarantees are self-financing, such as federal insurance on bank deposits. Other guarantees are policed by regulators, and yet others are implied but ambiguous and not spelled out in advance. But the end result is that actors in the financial system adjust their behavior — taking on more risk than they would otherwise — in ways that could create new, bigger problems in the future. As the Richmond Fed explains:

Implicit guarantees effectively subsidize risk. Investors in implicitly protected markets feel little need to demand higher yields to compensate for the risk of loss. Implicitly protected funding sources are therefore cheaper, causing market participants to rely more heavily on them. At the same time, risk is more likely to accumulate in protected areas since market participants are less likely to prepare for the possibility of distress — for example, by holding adequate capital to cushion against losses, or by building safeguarding features into contracts — and creditors are less likely to monitor their activities. This is the so-called “moral hazard” problem of the financial safety net: The expectation of government support weakens the private sector’s ability and willingness to limit risk, resulting in excessive risk-taking. …

The Richmond Fed’s view is that the moral hazard from the [Too Big To Fail] problem is pervasive in our financial system. The U.S. government’s history of market interventions — from the bailout of Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company in 1984 to the public concerns raised during the Long-Term Capital Management crisis in 1998 — shaped market participants’ expectations of official support leading up to the events of 2007-08. According to Richmond Fed estimates, the proportion of total U.S. financial firms’ liabilities covered by the federal financial safety net has increased by one-third since our first estimate in 1999. The safety net covered 60 percent of financial sector liabilities as of 2013. More than 40 percent of that support is implicit and ambiguous.

Bacon’s bottom line: While the current financial regime did alleviate the pain of the 2007 market collapse, the system could be allowing even bigger risks to build up. Like generals fighting the last war, regulators are fighting the last panic. The new risks will not be the same as the old ones, and we won’t know what they are until they explode in the next financial debacle. But spurred by the Fed’s near-zero interest rate policies, investors are chasing higher returns by taking greater risks, and financial markets are concocting elaborate new financial instruments to circumvent the regulators.

The global derivatives market was calculated in 2013 to be roughly $1.2 quadrillion in notional value, or about 20 times the global economy. Admittedly, most of that is tied to interest rates, currency values and stock indexes, not the economic sectors guaranteed by the federal government. But it illustrates how arcane financial instruments can magnify or hedge risks in ways we mere mortals — and government bureaucrats earning low, six-figure salaries — can barely comprehend.

I don’t know what will trigger the next financial crisis. Most likely, it will come from a quarter that most people would never expect. I don’t know when it will come. But the history of capitalism since the South Sea Bubble of 1720 suggests that one will come along eventually. If a bunch of multibillionaire hedge fund managers lose multibillion dollar bets and wind up selling apples on the street, I will lose no sleep. But if those hedge fund multibillionaires’ losses are back-stopped by federal loan guarantees, effectively socializing their losses, I will have a deep and abiding rage.