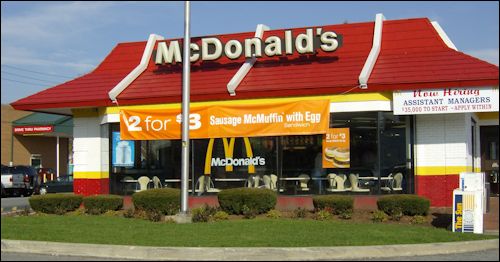

McDonalds is one of those American companies that the fashionable set love to hate. Critics gripe about everything from the nutritional quality of its food to the way it sources its beef. One recurring source of scorn is how the restaurant chain undermines community character by building loud, garish stores, typically surrounded by asphalt on locations accessible only by automobile. It’s not clear to me whether McDonalds is imposing some atrocious architectural template upon its stores nationwide or whether the template is imposed upon McDonalds by the Euclidian zoning codes of jurisdictions across the United States. Regardless, there is nothing inevitable about the red roofs, golden arches and ticky-tack decor.

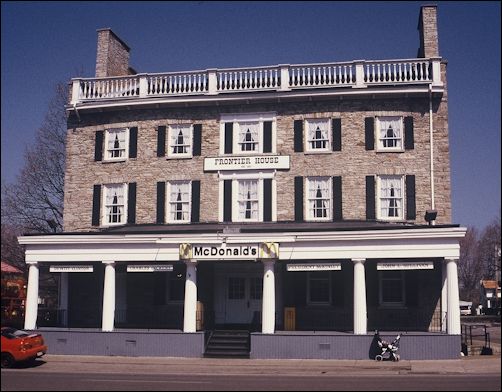

Ed McMahon, whose work on Virginia tourism and land use I highlighted in a recent blog post, responded to a comment in that post to the effect that “McDonalds didn’t make billions by letting locals operate different restaurants under a common banner.” Actually, he says, McDonalds is more flexible than most people realize.

“I just wanted to point out that McDonald’s does indeed allow locals to operate restaurants that are totally different architecturally from what most Americans are used to seeing,” he says. By way of proof, he offers some of the photos he has collected of McDonalds restaurants around North America and Europe.

And just for good measure, here is a photo of a Burger King in Chesterfield County, Va., suburban shopping mall setting, published in an article McMahon wrote about the architecture of fast food restaurants. The generalizations that apply to McDonalds apply to many other fast food companies.