by James A. Bacon

By investing more aggressively in industrial efficiency, Virginia manufacturers could reduce carbon-dioxide emissions by 2.6 million tons annually by 2030 while saving themselves a cumulative $4.1 billion. That’s the conclusion of a new study, “State Ranking of Potential Carbon Dioxide Emission Reductions through Industrial Energy Efficiency,” published earlier this month by the Alliance for Industrial Efficiency, an Arlington-based group comprised of representatives from the business, environmental and labor communities.

Virginia ranks 26th among all states in energy-saving potential through industrial efficiency, relatively low given the size of the state’s population and GDP. The top states in the ranking are those with large, energy-intensive manufacturing sectors. Still, under the Alliance’s scenario, the potential electricity savings of 3,000 megawatts in the Old Dominion would be roughly equivalent to the output of two state-of-the-art natural gas-fired power stations.

The study did not say how much it would cost Virginia industry to achieve the $4.1 billion in cumulative savings (averaging $292 million per year), however, so it is impossible to estimate a Return on Investment or compare the expenditure to alternate uses of capital.

Nationally, industry currently spends $230 billion a year on energy. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, nearly all growth in U.S. energy demand from 2012 to 2025 will come from the industrial sector. Over that period, demand is projected to increase from 22% of total U.S. energy consumption to 36%.

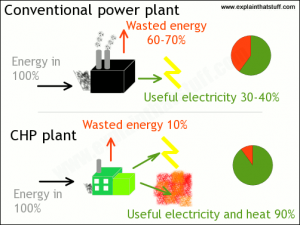

While many manufacturers already invest billions of dollars each year in energy efficiency, the Alliance argues that it could profitably invest even more, particularly by utilizing Combined Heat and Power (CHP) and Waste Heat to Power (WHP) generating systems. Both systems capture waste heat from electric power generation and utilize it to run a secondary power-generation process.

The Alliance derives its estimates from a scenario in which state regulatory policy encourages manufacturers to achieve 1.5%-per-year gains in energy efficiency through 2030 over and above what they would achieve on their own. State regulators can create the conditions for such efficiency gains by embracing the Clean Power Plan, currently in legal limbo until a U.S. Supreme Court ruling expected next year, the Alliance says. The plan allows considerable latitude in how to implement the CO2 reduction goals, such as closing coal plants, investing in gas-fired capacity, installing more renewable energy, and achieving gains in energy efficiency.

The Alliance argues that energy efficiency is the cheapest source of energy. “The cost of running efficiency programs in 20 states from 2009 to 2012 had an average cost of 2.8 cents per kilowatt hour — about one-half to one-third the cost of alternative new electricity resource options. Further, industrial efficiency is the cheapest source of efficiency,” states the study.

Manufacturers typically limit efficiency investments to projects that will be paid back in less than two years, creating a high hurdle for large capital projects like CHP and WHP. But a well-designed efficiency program, argues the Alliance, would change the economic logic.

One way to encourage industry investment is to dispense emission rate credits (ERCs) to industrial energy users that verify reductions in energy consumption. These credits could be sold on secondary markets, thus offsetting some of the cost of installing the energy-efficiency systems.

Another option is to allow utilities to participate in the installation of CHPs and WHPs. Utilities have different Return on Investment hurdles that might make them more willing to invest in projects that may take more than two years to pay off. In theory, the utilities could pay for the full investment, own the co-generation facilities, make an acceptable ROI on the capital invests, and pass on savings to the industrial customer.

“Utilities are particularly well-suited to help finance CHP projects because they can make long-term investments and often have strong existing relationships with potential host facilities,” states the study. “Such projects can be mutually beneficial to the utility and the host, especially if the project is located in an area with load congestion problems.”

As a bonus, CHP systems can improve electric reliability because they have the ability to operate independently of the grid, serving power and thermal needs during outages. These facilities can serve as “places of refuge” during hurricanes, ice storms, earthquakes or other natural disasters.

Bacon’s bottom line: Investing in industrial energy efficiency makes sense in theory. Not only would energy efficiency reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but it could lower the energy costs of Virginia manufacturers, making them more competitive in national and international markets.

However, the Alliance for Industrial Efficiency analysis raises one big question in my mind. The assumption is that investing in CHP and WHP at the factory level can achieve big energy gains. But big electric utilities like Dominion Virginia Power, whose operations I am most familiar with, are building combined cycle gas-fired power stations that use essentially the same process — generating electricity with combustion turbines, using the waste heat to power steam-generated electricity, and then recycling the waste heat from the steam-driven generation. The giant power stations enjoy economies of scale that make them more efficient than power plants designed to serve a single industrial customer. Where is the gain in efficiency? Perhaps readers better informed than me can explain in the comments section.

The Alliance mentions one other way in which industrial energy-efficiency investments might make sense: in localized situations where there are congestion load problems. Here in Virginia, one instance leaps to mind — the situation in the Williamsburg-Newport News area, where the planned shutdown of Dominion’s Yorktown power station will create a vulnerability to electric blackouts unless, Dominion says, electric power can be supplied from outside the region through a new electric transmission line crossing the James River. Objecting to the project on the grounds that it will disrupt viewsheds of an irreplaceable historic asset, foes have argued that Dominion should consider some combination of renewable energy, energy efficiency and a smaller transmission line that can run underneath the river at not unreasonable cost.

Does the potential exist to implement CHP or WHP for big industrial customers like Newport News Shipbuilding, Canon Virginia, Siemens or the Jefferson Labs? Could deals be structured in which Dominion invests profitability in co-generation facilities, creates energy cost savings for the industrial customers, and reduces the need to string a high-capacity electricity line across the James River? I don’t know the answer, but given the unique circumstances of the Virginia Peninsula, investments in energy efficiency might offer a better payback than elsewhere. Whether the Clean Power Plan goes into force or not, the State Corporation Commission should examine the pros and cons of such an option.