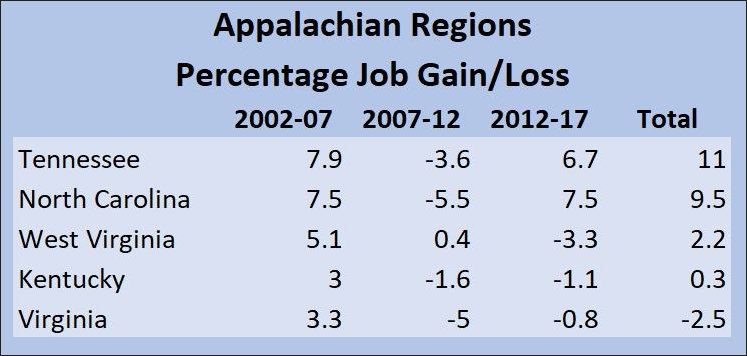

Employment growth in Virginia’s Appalachian region since 2002 has been the weakest of all five states in the Central Appalachian region, according to data contained in a recent Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) report, “Industrial Make-up of the Appalachian Region: Employment and Earnings, 2002-2017.”.

Making matters worse, job growth in Central Appalachia was the worst in all of Appalachia, which was half that of the United States as a whole.

The growth gap between Virginia on the one hand and Tennessee and North Carolina on the other has been particularly marked, the gap between Virginia on the one hand and West Virginia and Kentucky not quite as bad.

Earnings growth in Appalachia also has severely lagged that of the United States as a whole — 17.5% compared to 27.3%.

One obvious explanation for the dismal economic performance in Central Appalachia is the heavy dependence upon the coal mining industry, which has been in steady decline for more than two decades. Unlike West Virginia, where fracking-driven gas production partially compensated for declining coal output, Virginia has no fracking industry to offset the loss of coal employment.

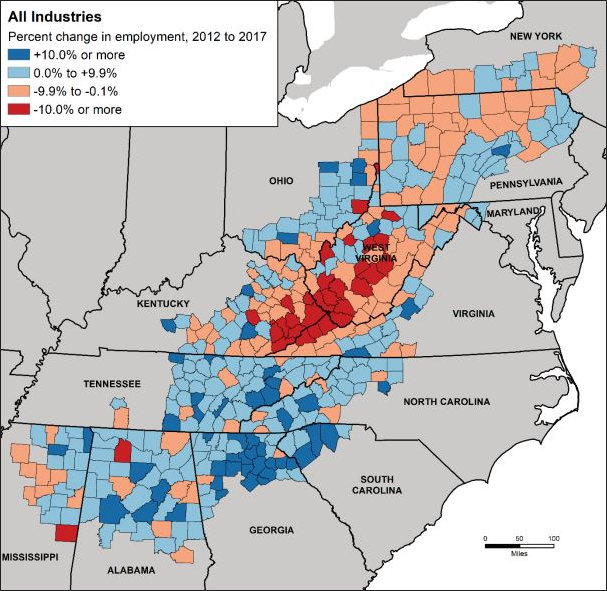

Another likely factor is the heavily rural nature of the economy in Virginia’s Appalachian region. Tennessee’s Appalachian territory includes the Knoxville and Kingsport-Johnson City metropolitan statistical areas, while the “Appalachian” region of Virginia has only the much smaller metros of Bristol and Blacksburg. Nationally, rural counties (those not adjacent to a metropolitan area) showed zero growth overall during the time span covered; growth rates were modest but positive for counties bordering a metro area, stronger for small metros, and strongest for large metros.

Bacon’s bottom line: Virginia’s Appalachian counties are affected by factors beyond their control — the sharp decline of the coal industry and the lack of a major metropolitan area. There is no replacing the coal industry, which is a spent force and will remain nothing more than a niche industry. But something can be done about the lack of a major metropolitan area — not right away, but over an extended period of time — by concentrating the allocation of economic-development resources.

The key is understanding the powerful economic logic that drives economic activity to metropolitan areas. Employers seek to locate in large labor markets with a depth of what a recent study refers to as “non-routine workers,” or workers who perform non-routine jobs (largely synonymous with the “creative class”), according to a recent study. The interaction on non-routine workers creates synergies. The more non-routine workers there are in a metro, the more economically productive they become.

Knowing this, it is folly to continue devoting scarce economic-development resources to maintain the current, predominantly rural/small town development patterns of Western and Southwestern Virginia. The region needs to de-ruralize or, put another, way it needs to concentrate its population in metros like Blacksburg, Bristol/Abingdon, and possibly others that have the potential to graduate to micropolitan or small-metro status. There is no chance of matching the job and wage growth rate of America’s major metros, but there is hope of at least entering a modest-growth track.

Pursuing such a strategy will be difficult, of course. Rural counties will fight for every scrap of state and federal aid they can get, and the political temptation to spread the goodies is a powerful one. But the only long-run hope of revitalizing Virginia’s Appalachian economy is to focus resources in a handful of mini-metros that can compete for labor and capital.

The study referred to above, co-written by Pierre-Daniel Sarte and Felipe Schwartzman with the Richmond Fed and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg of Princeton University, challenges the view that “cognitive hubs” in large U.S. cities must inevitably exacerbate geographic inequality. They write:

We argue instead that the formation of these cognitive hubs in large U.S. cities should be encouraged, but that the U.S. also needs to create similar hubs elsewhere for workers in more routine occupations. We demonstrate that designing these hubs as occupation-specific can be beneficial for everybody and can correct for, in the future, the wage inequalities and spatial polarization of workers we see today.

The authors envision using tax policy as the tool to drive the optimum distribution of workers geographically. The proposed “tax and transfer” system, which would redistribute money from non-routine workers to routine workers, is a political non-starter. But the paper does serve the useful purpose of focusing attention on the relationship between economic development and the size and depth of regional labor pools. Think of it as a conversation starter that Appalachian Virginia — indeed, all of rural Virginia — needs to have.