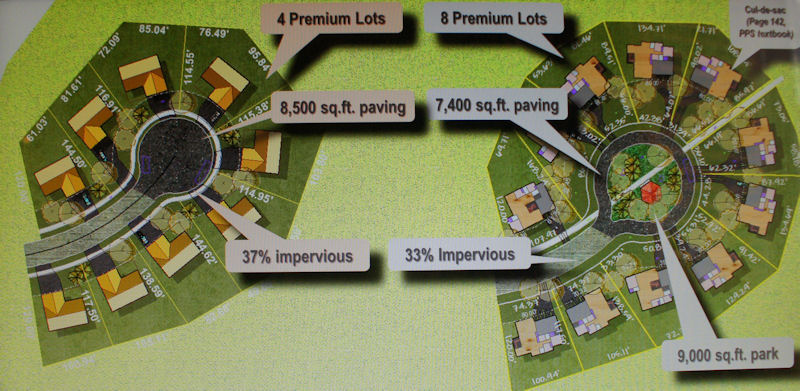

Upper image: conventional cul-de-sac subdivision. Lower image: a Prefurbia subdivision. (Image credits: Rick Harrison)

by James A. Bacon

The conventional suburban cul-de-sac is a planning and architectural dead end, maintains Rick Harrison, a Minnesota designer of residential communities. But rather than abandon the traditional suburban development model, as New Urbanists and smart growthers advocate, he proposes to reinvent it.

Grid streets, the solution proffered by the New Urbanist movement is not a viable alternative, Harrison argues. They increase the ratio of street surface to housing, driving up paving costs and creating more storm-water run-off. A better option, he suggests, is a design innovation he calls “coving,” which organizes neighborhoods around around long, curvy streets.

Harrison may not have the name recognition of a Peter Calthorpe or Andres Duany, gurus of New Urbanism, but there is no denying his success in the marketplace. His Rick Harrison Site Design Studio has designed more than 800 projects around the country accounting for $50 billion in development. Eighty percent of all new development in the country is suburban, he argues. Why not make it more efficient?

He took his case to the American Dream Coalition annual conference last week. I am a big fan of smart growth and New Urbanism but I found his ideas fresh and intriguing. As long as millions of Americans prefer living in low-density, auto-centric neighborhoods and builders continue delivering what they want, it is well worth exploring ideas to make these suburban communities less expensive and more fiscally sustainable.

Harrison’s big beef with cul de sacs is that they they dedicate too much surface area to streets and they interrupt driving flow. His designs, he claims, can shave infrastructure costs by 25% or more (60% compared to grid streets). What’s more, the smooth-flowing layout of his streets allows residents to reach their homes without the repeated acceleration and deceleration that consumes time and gasoline, and it ekes out more premium lots that developers can sell at higher prices.

The best way to describe his concepts, which he details in his book Prefurbia, is through pictures. The top image above, captured from Harrison’s presentation, shows a typical suburban subdivision design with two entrances, 12 internal street intersections and four cul de sacs. The lower image reconfigures the layout with two entrances, only two internal intersections and one cul de sac.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Harrison’s design is that it requires roughly 25% less road surface. The savings can be used to lower the price of the lots, increase the developer’s profit margin or accomplish both. Less roadway also translates into lower ongoing costs for whoever is responsible for maintaining the subdivision roads.

Less evident is the fact that Harrison’s design allows faster travel times for residents driving between their houses and the subdivision entrances. A car travels 200 feet to accelerate from zero to 30 miles per hour, and another 200 feet to decelerate to a stop. In cul-de-sac subdivision, a driver would be continually accelerating and delerating, consuming time and gasoline. The continuous loop in Harrison’s design allows continual movement at the posted speed limit.

Harrison touts one other design feature that I find interesting. He (or someone else who he has borrowed the idea from) has reinvented the cul de sac.

When you absolutely must have a cul de sac and nothing else will do, make it a small circle not a vast pad of empty asphalt. Fill the center with a landscaping — make it a small park. The layout yields higher-priced lots, requires less paving and creates less impervious surface. Oh, and it leaves room for fire trucks and snow plows.

I imagine that some people will criticize Harrison for trying to improve a settlement pattern that is beyond redemption. He may improve the driving experience within the subdivision, but he still displaces traffic to clogged collectors and arterials. He may design walking trails in his community, but a few paths don’t create complete streets, much less accommodate mass transit. He can dress up the sprawl, but it’s still sprawl. Those criticisms would be totally valid. Regardless, I like to see innovation. It forces New Urbanists and smart growthers to up their game.