The economy is chugging along at a 3% growth rate, unemployment is hitting record lows, productivity is surging. The economy looks like it’s in fantastic shape. A friend of mine and long-time Trump hater, normally disinclined to give the president credit for anything, marveled recently that the low-inflation, low-unemployment economy “is as good as it gets.” I hope like heck it stays that way.

But I am an inveterate worry wart. I’ve lived through booms before — the 1980s savings & loan bubble, the 1990s tech bubble, the 2000s real estate bubble. I’ve heard the promises that “it’s different this time.” And I’ve seen the busts that followed. It’s a universal rule that most “experts” did not foresee the meltdowns coming. The same thing may be happening again. Very few are paying attention to the build-up of highly leveraged corporate debt, both in the U.S. and abroad.

I don’t know if the “junk bond” sector will precipitate the next recession. Perhaps the next downturn will originate overseas and spread to the U.S., and a meltdown in junk bonds will merely act as an accelerant to a broader collapse. Whatever the case, the $1 trillion market now represents a significant risk. State and local governments in Virginia need to acknowledge this and other risks lurking in the economy as they go about making spending and taxing decisions. Only a fool would assume that the decade-long expansion, one of the longest in U.S. history, will last forever.

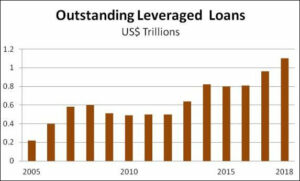

As seen in the chart above, reproduced in John Rubino’s blog, Dollarcollapse.com, leveraged loans made by banks to companies with weak balance sheets “clocked a 20% increase in the past year.” The expansion of the junk bond market was accompanied by rapid growth of less-regulated private credit and a weakening of underwriting standards generally.

(The Washington Post documented in April how the surge in junk bonds results from actions by the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress to reverse banking regulations enacted during the Obama administration. While I find the Post to be highly partisan and tendentious in its reporting on Trump, it does get the story right occasionally. This is one of those cases. Trump has been highly vocal about his support for an easy-money economic policy.)

The volume of leveraged loans in the U.S. financial system now exceeds $1 trillion and is twice as high when the economy collapsed in 2008. Writes Rubino:

This is the kind of problem that festers under the surface for a time before “surprising” everyone by blowing up and causing/contributing to a crisis. The reason it can fester is that in good times when credit is freely available, low-quality borrowers don’t fail. There’s always someone willing to refinance whatever loans come due, so default rates are extremely low. …

Today’s leveraged loans occupy just one of maybe a dozen pockets of extreme and growing risk that’s mostly hidden from even professional investors. Sub-prime auto loans and the bonds in which they reside, student loans, emerging market dollar-denominated debt, peripheral eurozone country (read Italy and Spain) sovereign debt, tech stocks; the list just keeps going. When one of these goes several if not all of the rest will follow, in what promises to resemble a fire in a munitions factory..

In 2003 Rubino, whom I had been fortunate enough to engage as a contributor to Virginia Business magazine when I was publisher there, wrote a book, “How to Profit from the Coming Real Estate Bust.” He highlighted the interrelated phenomena of the housing bubble, rising mortgage indebtedness, the decline in home equity, rising consumer indebtedness, the mortgage securitization mania, and the proliferation of financial derivatives such as credit default swaps. He saw the 2007 financial debacle coming years before most other people — so far ahead that had you taken his financial advice at that time, I’m not sure you would have made any money. Market manias persist far longer than any rational person would expect.

Junk bonds are just one pocket of risk. Rubino takes note of sub-prime auto loans and student loans here in the U.S. The federal government, of course, is $21 trillion in debt and running giant deficits. Though technically required to balance their budgets, many state/local governments have compiled massive “debts” in the form of unfunded pension liabilities and decaying infrastructure. And that doesn’t even touch upon the systemic risks posed by zombie corporations in China, over-leveraged banks in Europe, and Third World nations like Venezuela and Argentina teetering on the brink of sovereign default. In a globally connected world, financial catastrophe in one corner of the globe can transmit rapidly to other sectors via mechanisms we don’t even know exist.

The state of Virginia has made modest efforts this year to shore up its balance sheet, adding to its Rainy Day fund and financial reserves. But the state also increased taxes and expanded spending programs. It has huge future liabilities coming down the road — increased Medicaid expenditures, constitutional obligations to increase spending on K-12 to meet the so-called Standards of Quality, giant unfunded pension liabilities, and a deteriorating infrastructure. Those are the things we know are coming.

The General Assembly has made moves to identify weaknesses in local government finances in the hope of heading off another Petersburg-like meltdown. But no one is looking at the dozens (perhaps hundreds) of independent water/sewer authorities, solid waste authorities, industrial and economic development authorities, port and airport authorities, higher-ed institutions, transit authorities, community development authorities, and god knows what else. In other words, there are billions of dollars in obligations about which we know very little at all.

In the next post, I will explore how Virginia might turn this systemic risk and uncertainty to its advantage.