by James A. Bacon

The McDonnell administration’s justification for the $244 million Charlottesville Bypass is to preserve the integrity of U.S. 29 for freight traffic. Only one problem: Heavy trucks traveling north won’t be able to use it, according to an analysis published by the Charlottesville-Albemarle Transportation Coalition.

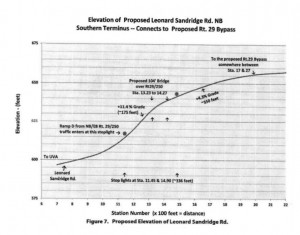

This cross-section shows the varying grades of the bottleneck at the Charlottesville Bypass’s southern terminus. Note: Height and distance measures are on different scales. Graphic credit: CATCO.

What’s more, the bypass will be unusable for some southbound trucks in snow, ice and perhaps even rain, says author Bob Humphris, a retired University of Virginia engineer who interviewed four trucking companies for the white paper, “A Tale of Two Roads.”

The crux of the problem is that the winner of the design-build contract, Skanska/Branch, made major changes to the original Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) design in order to shave costs, submit the low bid and bring the project under the $244 million set aside by the state. Skanska’s conceptual design shrank the footprint of the southern terminus, where the bypass ties into the U.S. 250 Bypass, eliminating the need to build three bridges and shortening the length of the on-off ramps. Those changes, says Humphris, reduced costs by $20 million or more.

But Skanska created problems with the new design. North-bound trucks serving manufacturing operations in Lynchburg, Danville and elsewhere would exit U.S. 250 onto a ramp onto Leonard Sandridge Road, which is classified as a Local Street System road, and encounter a stoplight. Then they would turn left and encounter another stoplight before entering the bypass.

VDOT recommends the addition of truck-climbing lanes for this stretch of Interstate 64 near Afton Mountain. The incline has half the slope of the steepest grade at the proposed southern terminus of the Charlottesville Bypass. Photo credit: News Virginian.

Humphris showed the plans to four trucking operations: UPS in Charlottesville, and to Estes Express, Lawrence Transportation System and Wilson Trucking in the Waynesboro-Fishersville area. None of these companies were aware of the new design, he says. UPS said that its light trucks would not be affected. But the other three told him that the operation of heavy trucks would be so impaired that they would route the trucks elsewhere.

Northbound trucks would encounter two problems. First, they could not make the tight left turn at the first stoplight unless they were in the right-hand land, and they would create a safety hazard by cutting off cars in the left-hand lane. Second, the incline after the first stoplight is exceedingly steep, with a grade of 11.36% — roughly twice the grade of the Interstate highway up nearby Afton Mountain, where truck speeds routinely fall below the posted speed limit.

Wrote Humphris: “Starting from a stopped position and trying to accelerate up the 162 [feet] of an 11.36% grade, and then another 163 [feet] of a 4.26% grade to the second stoplight takes a considerably longer time compared to automobiles — and quite likely two cycles of the stoplights would be required.”

The same steep incline would pose a hazard for south-bound heavy trucks in inclement driving conditions. “Bad, icy weather would be horrendous coming down that grade,” Humphris says.

Someone needs to inform the Danville and Lynchburg Chambers of Commerce, which lobbied heavily for the bypass project as a lifeline for their manufacturing-intensive economies, Humphris says. “To come off a highway of national significance onto the local street system defeats the purpose of the whole thing.”

Another set of problems arises from the re-design of the southern terminus, which arguably breaks an understanding reached in the 1990s with the University of Virginia by encroaching upon UVa’s northern grounds. University officials asked then that “every possible aesthetic measure [be] taken to preserve and enhance the University’s considerable investment in the setting and appearance of its new Darden School of Business and the Law School, including visual buffering … as well as acoustic buffering using sound walls faced with materials compatible with those historically in use at the university.”

Randy Salzman, a transportation writer who has closely tracked the U.S. 29 Bypass procurement process, says that the landscaping and acoustic buffering are missing from Skanska’s conceptual design — another trick the contractor used to trim costs from its bid. “Once construction begins,” he writes, “there must be major change orders.”

In correspondence to a UVa professor, he continues:

Skanska and bypass promoters realize that Darden and UVA will demand changes, which University Architect David Neuman has already begun, and the price will climb. The American Trucking Association will demand changes and the price will climb. Similar issues will likely show up in other sections of the 6.2 mile highway and the price will climb again.

All when the media and the public are no longer paying attention.

Bacon’s Rebellion tried contacting three different VDOT spokesmen for a comment Thursday, two in the Culpeper office and one in the Richmond office, but did not get a response.