Last Tuesday I joined more than 100 people for the inaugural meeting of the Campaign to Reduce Evictions (CARE), sponsored by the Virginia Poverty Law Center, at First Baptist Church in Richmond. We assembled for two hours to investigate why Richmond has the second highest eviction rate in the country among large cities and what can be done about it. The goal of the campaign is to produce recommendations by 2019 that state and local policy makers can use to craft solutions to the crisis.

Why are we talking about this — how bad is it?

Why are we talking about this — how bad is it?

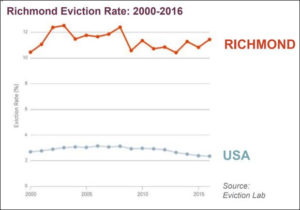

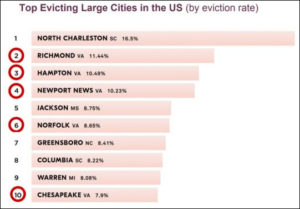

Richmond ranks #2 in the nation with an eviction rate of 11.44% with 6,345 evictions in 2016, according to data from the Eviction Lab. Roughly one out of every nine renters was evicted, or 17.38 households evicted every day. Comparing it to the rest of the country, Richmond is approximately five times the national average of 2.34%.

Moreover, Virginia has half the large cities with the country’s Top 10 highest eviction rates. Part of the reason is that Virginia, unlike many other states, has a legal process that favors landlords. (See eviction data for details.)

Moreover, Virginia has half the large cities with the country’s Top 10 highest eviction rates. Part of the reason is that Virginia, unlike many other states, has a legal process that favors landlords. (See eviction data for details.)

As Omari al-Qadaffi, a housing advocate from Leaders of the New South, points out, “An unlawful detainer is the only civil action in Virginia where an indigent person is compelled to pay the appeal bond. Any other civil action, you can be excused from it if you’re poor, but Virginia is such a real estate-friendly state that you cannot be excused from that. Also, something unique about Virginia is that a general district court is not a court of record, so there is no transcript that’s kept. So …in civil court, defendants just get run over top of in general district court, and cannot go back to a record to say ‘hey, my rights were deprived of me.’”

How is CARE approaching this?

CARE is conducting a series of meetings and workshops to create recommendations. The inaugural meeting was well organized and drew a cross-section of people and stakeholders involved in or affected by evictions. The breadth of stakeholder groups assembled was impressive — tenants who are in the process of being evicted and those who have been previously evicted, landlords, property managers, housing advocates and aid societies, housing authorities like Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority interim CEO Orlando Artze, attorneys, court personnel, and academicians.

The meeting started with a moving, personal story by Tonya Kernodle who recounted her experience being evicted as “emotionally devastating.” She admonished the audience to widen its perspective about who is evicted. “Don’t think it’s some type of person; it can be anyone.”

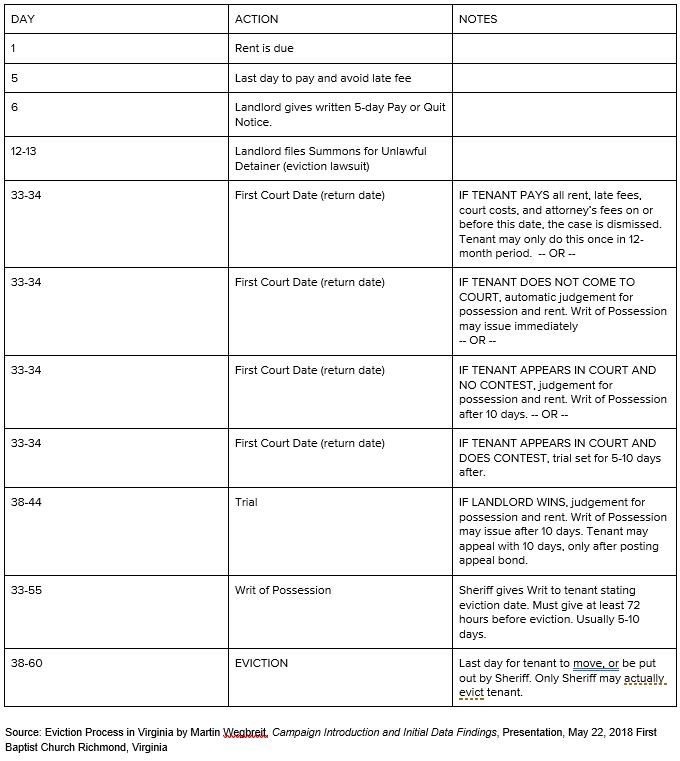

Martin Wegbreit, Director of Litigation for the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society, described the typical five-step eviction process, but noted that the duration can vary based on the court’s schedule and local practices. Nationally, 77% of evictions occur because of non-payment of rent and 23% for other reasons, like causing a public nuisance, poor building conditions, or calling the police too many times. Typically the process goes as follows:

Attorney Wegbreit noted how quick the eviction process is in Virginia and it favors the property owner, “the landlord [has many options] and has been made whole. The landlord has gotten all of the rent, all of the late fees, all of the court fees, and all of the attorneys fees and is out nothing, and yet the tenant can be out everything, if the landlord so chooses.”

Housing Development Consultant Jonathan Knopf and VCU Professor Kathryn Howell presented data on the scope of the problem in Richmond and statewide based on data from the Eviction Lab and the Supreme Court of Virginia’s records. The data is incomplete; it is missing from certain localities and sometimes the two data sets’ units of measure do not align. That said, their analysis showed:

- Eviction rates were probably underestimated. Christie Marra, Director of the ACES Community Development Initiative at the Virginia Poverty Law Center, stated that the Eviction Lab data is based only on the last writ of possession filed for a household, even though a household may have received multiple writs issued against it previously, likely resulting in an under count. Similarly, Martin Wegbreit surmised the published rates are lower than actual because they do not account for the number of renters who move after a writ of possession is issued but before the sheriff arrives at their door. Professor Matthew Desmond, director of the Eviction Lab, states in his book, “Evicted” that “the American Housing Survey, along with most material-hardship studies, significantly underestimates the prevalence of involuntary removal among renters by relying on open-ended [survey] questions that do not adequately capture informal evictions that many renters do not consider to be “evictions.”

- Certain sectors of Richmond had rates as high as 30%.

- Areas of the city with high eviction rates also had high poverty and were mostly single family neighborhoods.

All in all, there was a palpable commitment and passion brought by many participants to find a better way of handling this process because of its staggering human toll. Pam Kestner, Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development, said the Department has set aside a small amount of funds for a demonstration project about stabilizing housing for high school students in Petersburg. It will track the outcomes and the data to demonstrate to the Virginia General Assembly that if there were more money for stable housing that students would have better education outcomes.

All in all, there was a palpable commitment and passion brought by many participants to find a better way of handling this process because of its staggering human toll. Pam Kestner, Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development, said the Department has set aside a small amount of funds for a demonstration project about stabilizing housing for high school students in Petersburg. It will track the outcomes and the data to demonstrate to the Virginia General Assembly that if there were more money for stable housing that students would have better education outcomes.

Conclusion

According to Professor Howell, the principal drivers of Richmond’s eviction rate are a shrinking supply of affordable housing stock, development of non-subsidized housing, too high a rent burden (spending more than 30% of household income on rent). Likewise, Attorney Wegbreit believes that:

High poverty rate + lack of affordable housing + few tenants rights = High Eviction Rate

Additional research will answer some of these questions by pursuing several lines of inquiry. First, collect more data to fill in the gaps. Second, perform qualitative analysis of the eviction process, focusing on filings and households. Third, investigate housing stability and social impact, such as school performance, health outcomes, housing insecurity and homelessness, and job access and stability. Fourth, determine the fiscal impact to social services, sheriff’s costs, court costs, and housing provider costs. Fifth, examine who owns the properties with the most evictions. Property ownership is opaque because many rental units are owned by LLCs, making it difficult to determine if there are bad actors. Sixth, confirm if gentrification raises eviction rates based on the increased rent burden.

Over the summer, three workgroups will explore services for prevention, affordable housing supply, and law reforms. The groups will present their results in the fall at the next general meeting on September 25, then begin work on compiling recommendations.

For more information, please see https://www.reduceevictions.org/.

Henrico County resident Marc Lockhart is an advocate for social justice and community development. He formerly served on the board of directors for Goodwill of Central and Coastal Virginia and is a citizen data scientist examining issues at the intersection of income, authority, and inequality in Richmond.