by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon

As the Board of Visitors ponders how much to raise tuition & fees in the next two academic years, the University of Virginia is grappling with strong inflationary pressures and a long-term shortfall in state aid, senior university administrators said Wednesday.

Even so, administrators told the Board’s Finance Committee, UVa offers a great “value proposition” compared to other Top 50 universities. Its in-state tuition is lower than that of top private universities, and its four-year graduation rate is the highest of any public university in the country.

The Finance Committee meeting yesterday marked the beginning of a two-month decision-making process. The purpose of the initial meeting, said Committee Chair Robert M. Blue, was to provide “context” for the discussion. A November hearing will allow students and others to express their views about college costs. The Board is scheduled to adopt a new tuition structure in December.

Although university officials did not say explicitly that a tuition increase is justified, the “context” presented was geared to supporting such a conclusion. Board members offered no pushback during the one-and-a-half-hour session, asking only a few questions for purposes of clarification. They did not drill into the data proffered by administrators, nor, despite assurances that UVa was working assiduously to achieve efficiencies and reduce redundancies, did they ask for specifics. No one addressed faculty productivity, administrative overhead, or other drivers of university costs.

The primary presentations came from Chief Operating Officer J.J. Davis and Vice Provost for Enrollment Stephen Farmer. A PowerPoint containing their presentations can be viewed here.

Davis set the tenor of meeting. UVa, she said “is punching above its weight for being efficient and effective.”

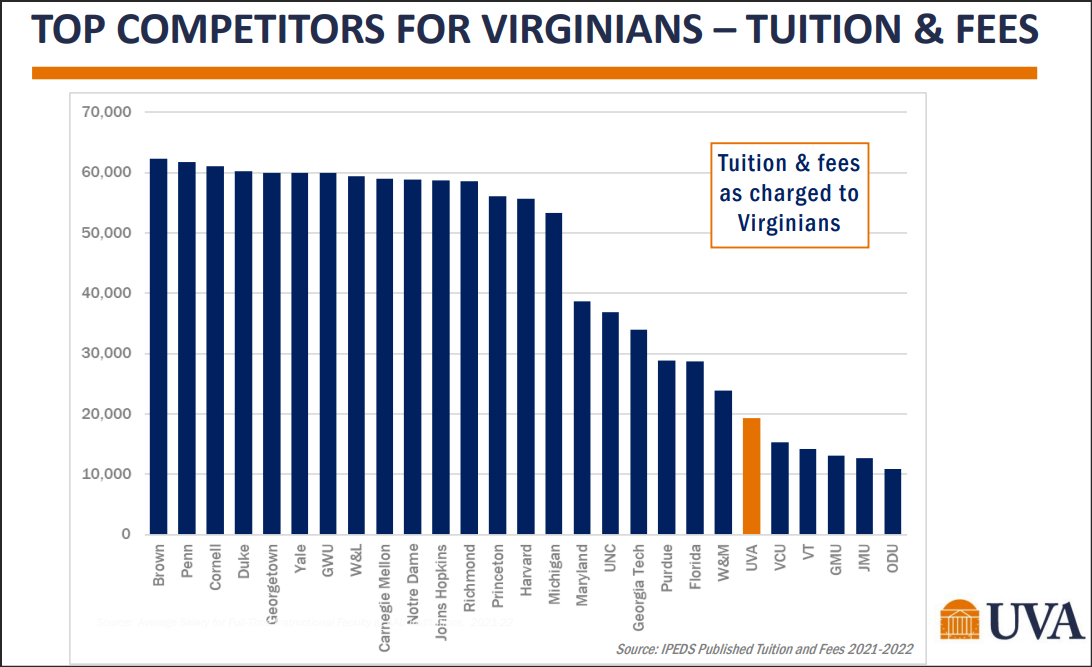

For Virginians, UVa tuition compares favorably to that of its top competitors (defined as institutions that applicants are most likely to label as their top alternative to UVa). The following graph shows tuition and fees charged by UVa, several nationally ranked private universities, and several public Virginia universities.

UVa appears in this presentation to be a great bargain. Note, however, that the graph compares gross tuition & fees, not net tuition & fees after discounts and financial aid. Private institutions discount tuition heavily for lower-income students; UVa does not. Also, the graph compares UVa’s in-state tuition with the out-of-state tuition charged by other public universities. It is valid as a measure of how competitive UVa tuition is for Virginia residents, but it says nothing about how well UVa serves its in-state students compared to how other public universities serve their in-state students.

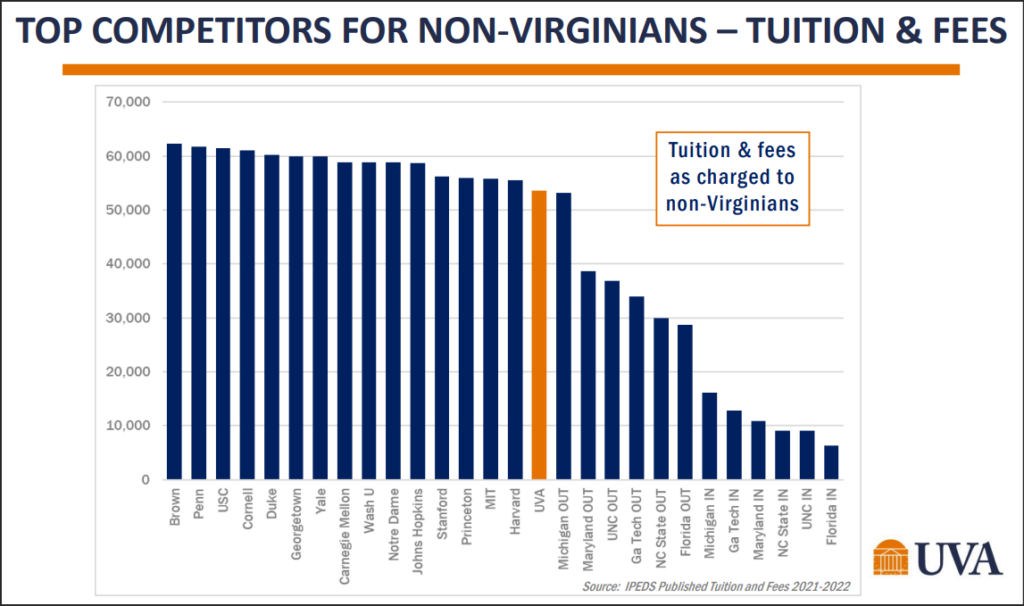

The following graph shows that UVa fares less well in the competition for out-of-state students. Even here the graph may overstate UVa’s competitive position. A comparison of net tuition would be a better measure.

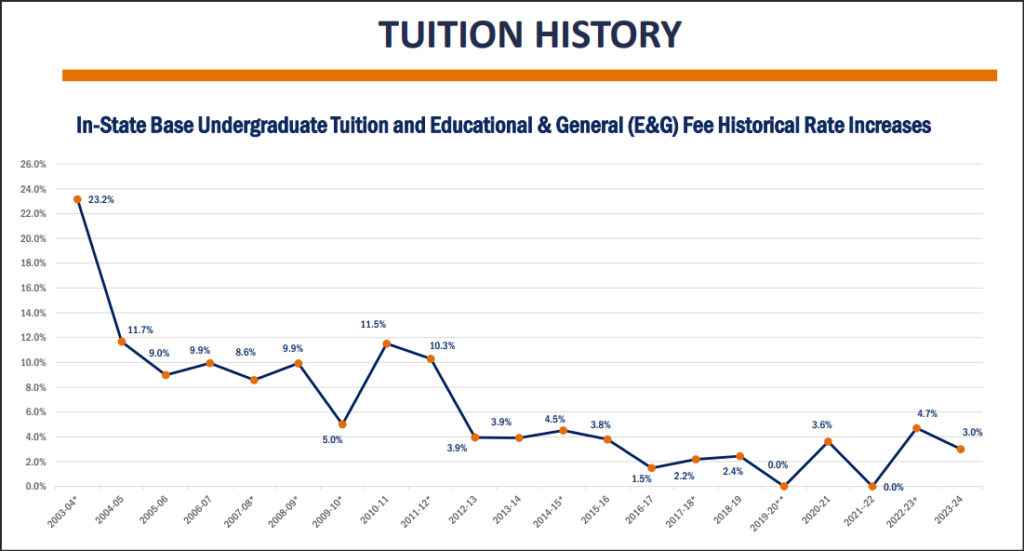

UVa officials also said that the Ryan administration has done a superior job in holding down tuition increases. The graph below shows how tuition increases over the past decade have been modest compared to the previous two decades. (Ryan became president in 2018.)

UVa charges for room and board have increased in line with the Higher Education Price Index (HEPI) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI), board members were told.

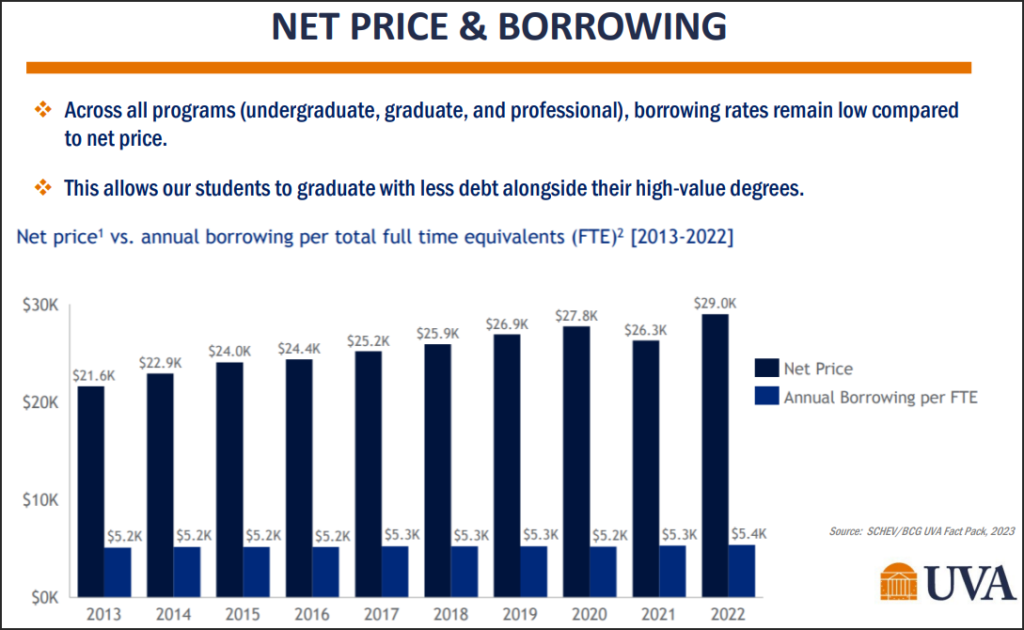

Thanks to the moderating increase in the total Cost of Attendance (tuition, fees, room, and board) and UVa’s success in growing its endowments for financial aid, per-student borrowing has not increased appreciably since 2013, UVa officials said. The following graph compares the “net” price of attendance (what students actually pay on average after grants and scholarships) and the average level of borrowing per student.

Missing from the graph is an indication of what percentage of students attending UVa borrow money to fund their attendance. By itself, the “average borrowing per FTE student” doesn’t tell us much. We can’t tell from this figure whether the number of students taking on debt is growing, shrinking, or stable, or whether they are borrowing more or less.

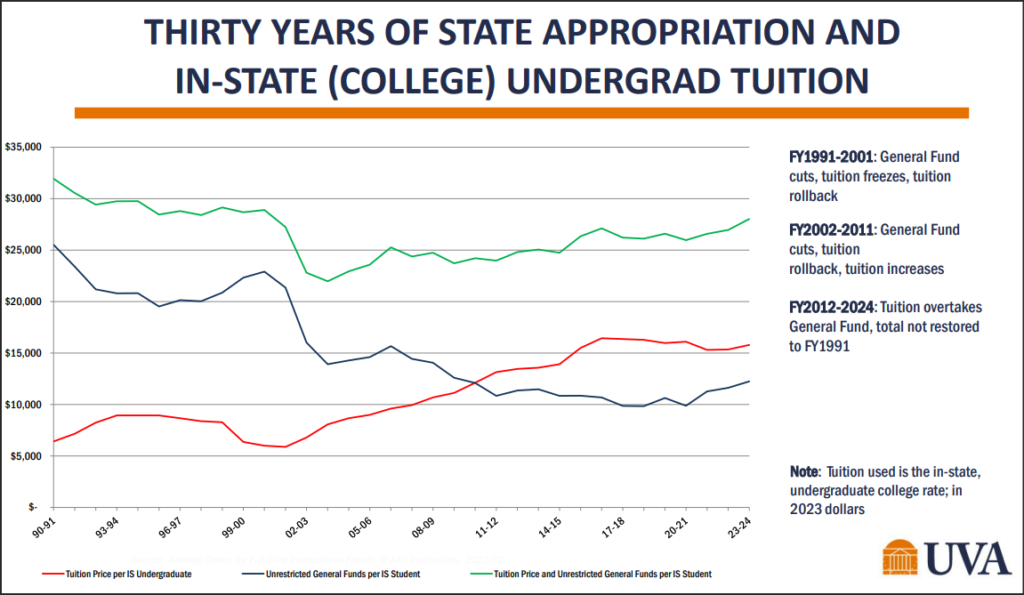

UVa officials also argued that UVa has managed to restrain tuition increases despite a long-term decline in inflation-adjusted state aid per pupil. State funds currently offset only half the cost of tuition for in-state students, a much lower ratio than in years past.

The following graph shows how undergraduate tuition per student (the red line) now surpasses state appropriations (the blue line) as university revenue sources.

This “context” is itself missing context, which I shall explore in a forthcoming white paper. A key point in our analysis: the decline in state support (adjusted for inflation and enrollment) explains only one-third of the tuition increase over the past 20 years.

Addressing inflationary pressures faced by UVa, Davis said that higher education is a “people-driven industry.” Overall, UVa increased compensation 17% in fiscal years 2022, 2023, and 2024 at a cost of $208 million. Of that, the university anticipates receiving an additional $34 million from the state. The balance will come from other funding sources: gifts and endowment income, direct and indirect research, auxiliaries and recoveries, and, of course, tuition.

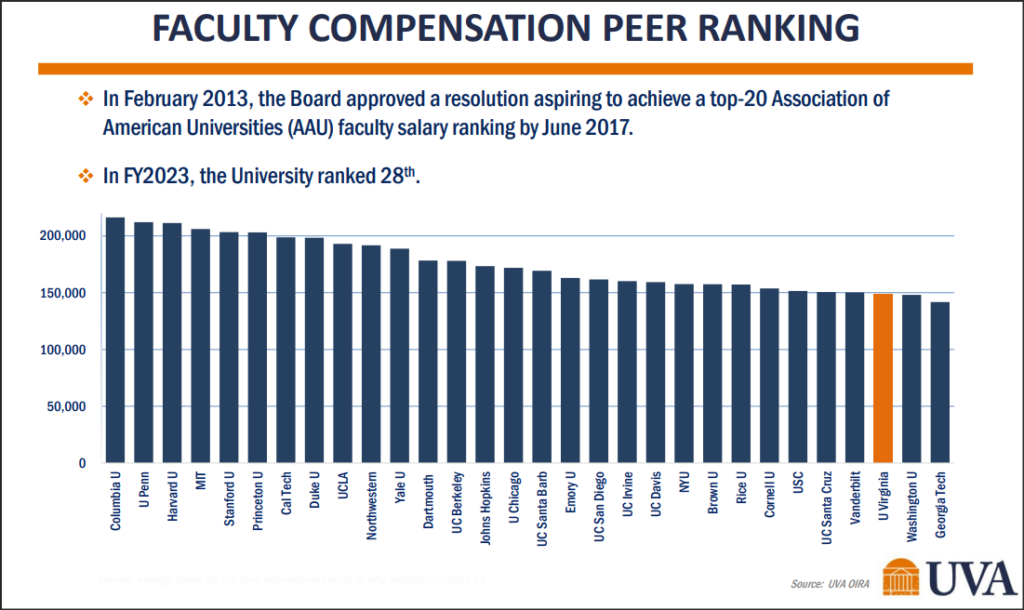

Looking ahead, UVa will remain under intense competitive pressure to recruit and retain top faculty and staff, a necessity for maintaining its national prominence. “Our compensation is below market — for both faculty and staff,” states the PowerPoint. Provost Ian Baucom told the committee that in exit surveys faculty members usually cite either compensation issues or more compelling research opportunities as their reasons for leaving UVa. The following chart shows UVa’s relative position compared to other top universities.

No board member asked what the comparison might look like if it adjusted for cost-of-living differentials in different cities. For example, Columbia University, which pays $50,000 higher salaries on average than UVa, is located in Manhattan. According to the Forbes cost-of-living calculator, a $150,000 salary, typical of full professors at UVa, would require an income of $331,000 in Manhattan to maintain a comparable standard of living.

Despite its challenges, UVa offers a competitive value proposition to students, Davis and Farmer argued. The university’s relative standing can be seen in two sets of measures: its graduation rate and its admissions statistics.

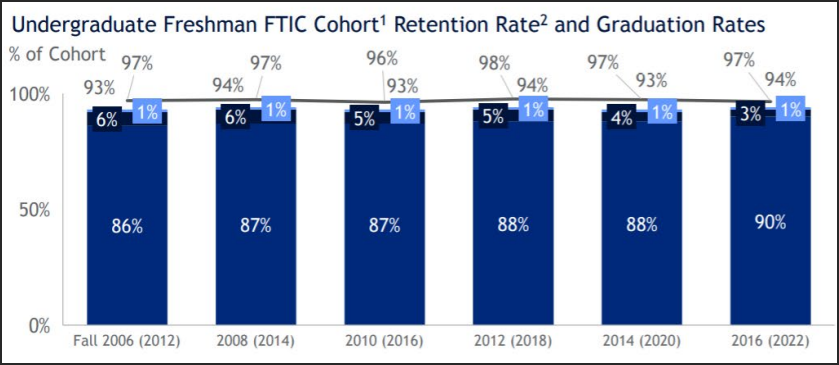

A point of pride is that UVa’s four-year graduation rate is the highest of any public university in the country, and it has been improving in recent years. Here are the numbers:

The 4-year graduation rate (dark blue) has improved from 86% for the entering class in the fall of 2006 to 90% for the entering class in the fall of 2016. (The numbers in black and light blue represent the percentage of students graduating in five and six years.) That’s significant because, as Farmer put it, “a four-year degree is cheaper than a five-year degree.”

The presentation did not address the fact that the four-year graduation rate is closely correlated with the socioeconomic composition of the student body. Students from affluent families are far more likely to graduate in the standard four years and less likely to drop out than students from lower-income families. UVa has been criticized by left-leaning higher-ed analysts for admitting a low percentage of lower-income students than peer institutions. No board member asked Farmer to discuss the extent to which UVa’s high graduation rate could be attributed to the composition of its student body.

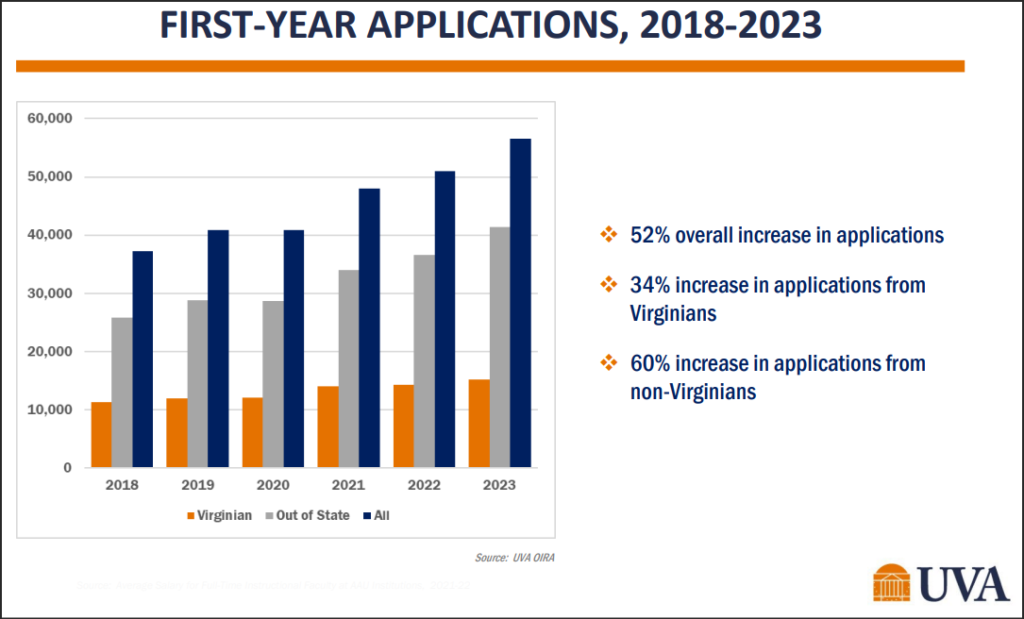

Farmer also cited admissions statistics as evidence that students recognize UVa’s value proposition. Despite a decline in the number of college-going students, he said, UVa is getting record numbers of applications, as seen here:

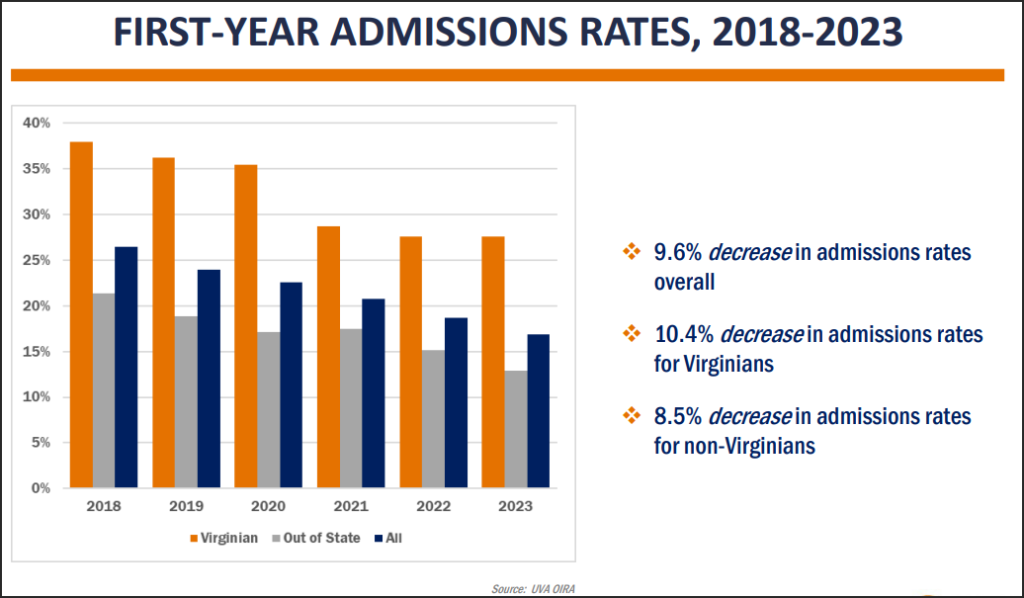

With applications on the rise, UVa has been more selective about whom it offers admissions, as seen here:

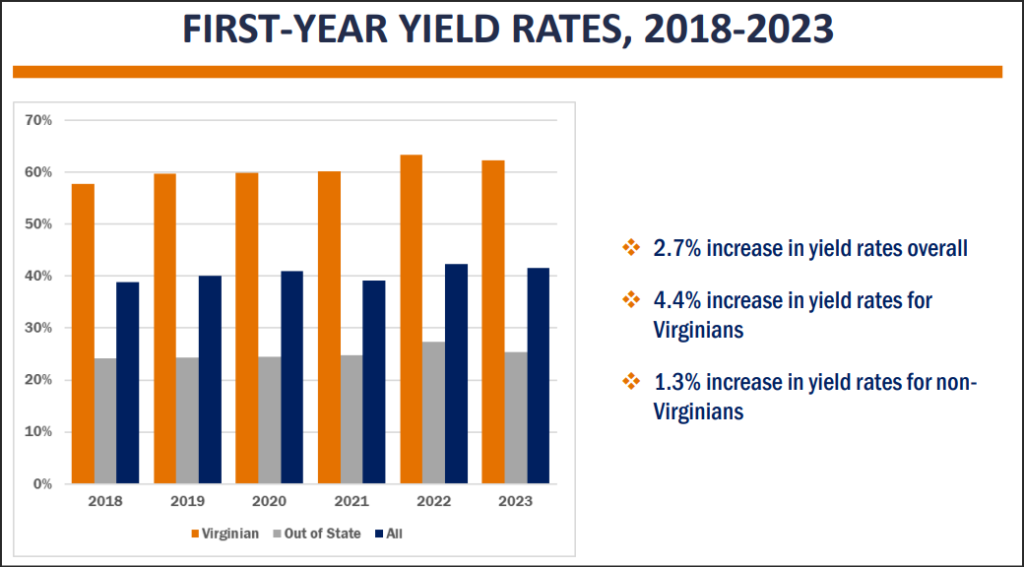

Finally, the percentage of students choosing to enroll at UVa after being given an offer (yield), has been edging up.

But there’s more to the admissions story. College applications have soared nationally in recent years because adoption of the Common Application has made it cheaper and easier for students to apply to more universities. Students are applying to more elite universities considered a “stretch,” or a longshot. Other elite universities have seen similar gains in applications. How do UVa’s applications, admissions and yields compare to its peers?

Farmer did address that point. It turns out that UVa’s experience is above average, but not exceptionally so. Among 52 top-ranked universities in the U.S. News & World-Report “Best Colleges” listing (which included 22 publics), UVa ranked as follows for five-year change in:

- % increase in applications: 17th overall, and 6th among publics.

- % decrease in admission rates (lower rates equate with greater selectivity): 22nd overall, and 4th among publics.

- % increase in yields: 31st overall, and 5th among publics.

My argument in this column is not that UVa is too expensive, does not offer an excellent value proposition, or cannot justify a tuition increase. Rather, I’m saying that the data presented is too incomplete to make an informed judgment. One expects college administrators to select data that puts them in the best possible light. One also might hope that a conscientious Board of Visitors would subject the administration’s narrative to critical scrutiny.

James A. Bacon is executive director of The Jefferson Council. This column is republished with permission from www.thejeffersoncouncil.com.