by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon

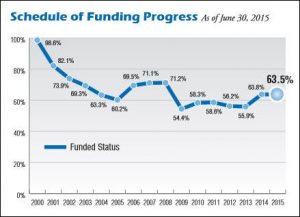

More bad news from Petersburg: The Southside city of 32,000 souls and 600 government employees has fallen more than 60 days behind on $2.3 million in pension payments. That development was reported by the Virginia Retirement System in a letter to state legislators, as required under a law that went into force this month.

The city has been forwarding the 5% payments deducted from employee paychecks but still owes employer contributions dating back to November 2015, with the exception of May, when it managed to make a payment, reports the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Petersburg closed the 2015 fiscal year with a $17 million budget deficit, roughly 20% of revenue, and, despite cutting the pay of city employees, has yet to devise a plan for closing the gap in the current fiscal year.

Petersburg is the only locality in Virginia that is delinquent on its pension payments, said VRS spokeswoman Jeanne Chenault. The city, she added, is “committed to paying those [outstanding] contributions and they are working on a plan to do so.”

Bacon’s bottom line: I don’t mean to beat up on Petersburg, which just may be the worst hard-luck case in Virginia. But the city’s travails are unprecedented in modern times. I don’t recall anything comparable in my 40-year journalism career. I wouldn’t be surprised if closing the fiscal year with a massive deficit in defiance of state constitutional requirements for a balanced budget has no parallel since the Great Depression.

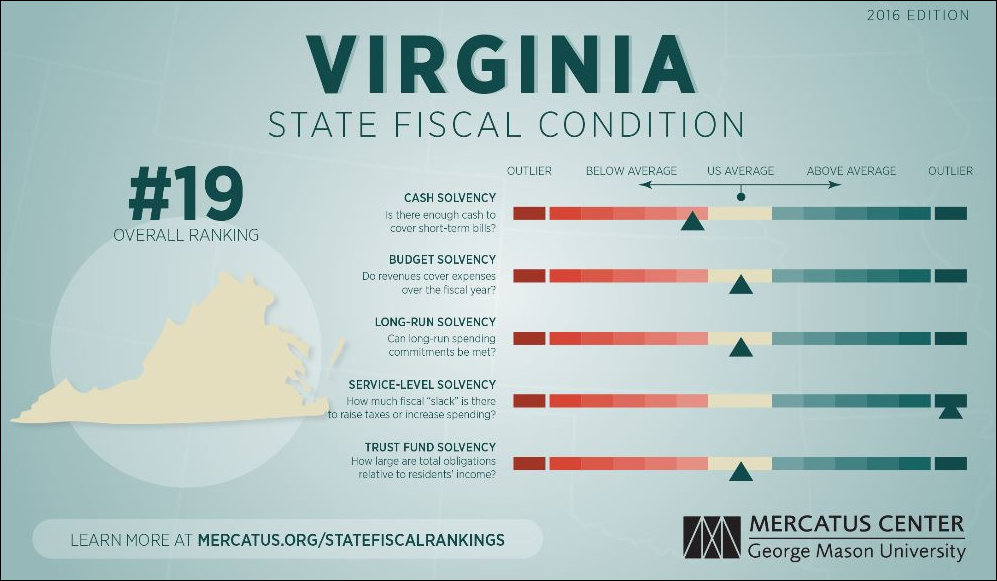

The first big question in my mind: Is this an aberration due to one-time factors unlikely ever to be repeated? Or are Petersburg’s woes symptomatic of a deeper malaise throughout Virginia? Have other localities, particularly those with depressed economies, “balanced” their budgets by deferring maintenance, slow-paying creditors or engaging in other accounting tricks? I have written about the small city of Buena Vista, which defaulted on a $9.2 million bond issue to pay for a municipal golf course, as a fiscal canary in the coal mine. (Speaking of coal mines, I’d be amazed if the coal-producing counties of Southwest Virginia, having seen their primary industry go up in soot, weren’t experiencing serious fiscal stress.)

Here’s the next question: What we do about Petersburg? By “we” I mean the citizens and elected officials of Virginia who represent us. Should we let Petersburg figure things out by itself? What if it can’t? What if the politics are so dysfunctional, the underlying economy is so weak, or the choices are so hard that elected officials can’t manage the task of balancing the budget?

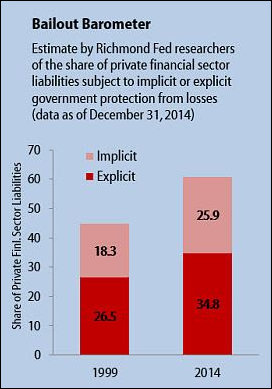

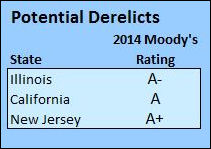

Do we just look the other way? Do we pretend that Virginia’s constitution doesn’t required balanced budgets? If so, do we create a moral hazard that encourages other localities to say, what the heck, Petersburg got away with it, maybe we can, too? Or, conversely, do we bail out Petersburg? And if we do, what concessions do we extract in return?

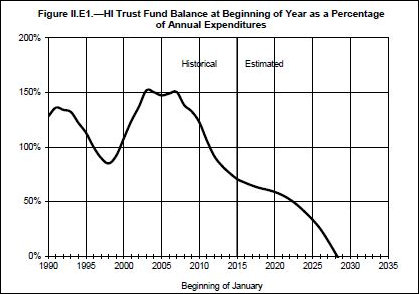

It is no exaggeration to refer to Petersburg as “Detroit on the Appomattox,” because, when there is a 20% gap between revenue and expenses, there is a significant possibility that the city can never climb out of the hole it has dug for itself. If that happens, Virginia will face the same kinds of unpalatable decisions that Michigan did with Detroit and Flint. I don’t know if Virginia even has a legal structure to deal with such a situation. Would we put Petersburg into receivership and, overriding normal democratic institutions, appoint someone to run the place?

So far, there has been no public response from Governor Terry McAuliffe. There hasn’t been much of a response from the General Assembly either, although the law requiring the VRS to report localities that fail to make their pension payments did originate from the legislature. At least someone is paying attention.