by James A. Bacon

This is my kind of environmentalism: The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has purchased more than 800 acres in Giles and Bland counties to preserve two old-growth forest communities dominated by northern red oak and chestnut oak.

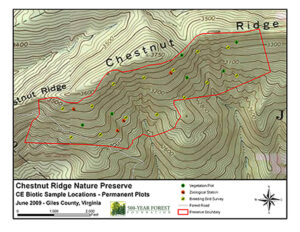

The old-growth communities exist in a “large matrix of nearly unbroken forest,” the extent of which is rare in western Virginia, according to the DCR website. Natural Heritage ecologists have confirmed the existence of individual trees between 300 and 400 years old.

Originally, Bob and Darlinda Gilvary, owners of Gilginia Tree Farm LCC, established a 233-acre preserve and managed the forest, selecting and harvesting individual trees themselves. They took care to leave the oldest trees and other mature stock for regeneration, reports WXFR. They also obtained a conservation easement for the land. “Years ago, my husband and I decided to keep the whole land in [the] forest. We did it to protect the environment and to protect water quality. It is important to use to leave it in good hands,” said Ms. Gilvary.

Now the state has acquired that land and added 587 acres of adjacent property. The entire 820 acres are permanently protected as part of the Virginia Natural Area Preserve System managed by the Virginia Natural Heritage Program at DCR.

The property is not readily accessible to the public — no parking areas or established trails — but the DCR will explore the feasibility of public access in the future. In the meantime, visitors may visit the site by contacting the 500-Year Forest Foundation, a Charlottesville nonprofit dedicated to preserving old-growth forests. The group’s website describes the importance of preservation:

Old-growth forests are our most endangered forests. The few that remain outside national parks and wilderness areas are becoming increasingly threatened. In the Eastern states, they account for only one quarter of one percent of all forests—a huge loss. A first-time worldwide study showed a drastic decline in the number of big trees, the defining anchors of old-growth forest ecosystems. Forests were here long before man, but human remaking of the landscape that began thousands of years ago has rapidly accelerated, halving the earth’s forest cover. Now our forests face the threats of climate change, while a global economy has introduced tree-killing fungi and insects along with non-native invasive plant species that multiply rapidly and crowd out native species. Our forests are in biological shock.

500-Year Forest works with landowners to protect old forests, developing plans to control invasive species — and invasive deer.

Bacon’s bottom line: Virginia’s save-the-world environmentalists are focused on combating climate change by decarbonizing the economy — first the electric power industry, and then the transportation sector — at the cost of billions of dollars. The obsession with CO2 and global warming consumes most of the political oxygen, so to speak, that can be devoted to environmental protection. Meanwhile, here in Virginia, pennies on the CO2 dollar go to causes such as habitat preservation.

Technological innovation and new business models are slowly but surely decarbonizing the economy anyway — the process just isn’t fast enough to satisfy the save-the-world environmentalists. I’d like to see more resources dedicated to saving Virginia’s environment.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.