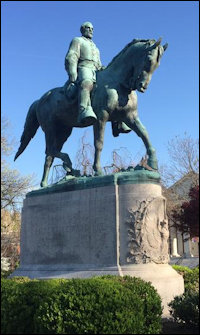

There is a move afoot in Charlottesville to remove the statue of Robert E. Lee. Rather than spend tax dollars to remove the statue and rename the park, perhaps Charlottesville City Council should consider a higher-order solution pioneered by the people of Australia.

White Australians in the 1800s were as brutal than the worst American slave owner, perhaps more so; they treated Aboriginals with a viciousness few can imagine today. Often, when a European settler, or his cow or sheep, disappeared, white Western Australians gathered guns and horses and went out and murdered members of the nearest Aboriginal tribe. Punishing every Aboriginal they could — even if no tribe member had committed any crime and often unsure that any actual crimes had been committed — the theory of these so-called “punitive expeditions” was that any remaining Aboriginals would never harm whites’ livestock in the future.

Lasting over 100 years, the final “battle” between spears and rifles took place in 1934. By then, white Australians had built statues and monuments honoring the “brave” members of earlier punitive expeditions and, after one, a particularly horrendous massacre of about 70 mostly women and children, a popular song was written to honor the leader.

By the turn of this century, with the publication of such books as “Why Weren’t We Told,” by Henry Reynolds, even the most strident white Australian began realizing that, as one historian put it, the celebrated “punitive expedition is most likely a euphemism for massacre.”

But rather than tear down the monuments and statues, the Aussies hit upon what I think Charlottesville should do with Lee and Jackson statues. They added another version, the Aboriginal version, to the monument’s story. Today, in places like Fremantle, Western Australia, the old statutes have bronze plagues explaining that there at least two versions of what happened, and why. In some cases, there’s a competing monument.

The history, good and bad, isn’t eradicated. Instead, it’s expanded in a manner which illustrates that all versions of life are seen through flawed human eyes. William Faulkner’s truism that “The past isn’t dead: It isn’t even past” is obvious to anyone reading the monuments.

Humans simply don’t know how our present actions will be perceived in future times; nor apparently do we know if what we do today is actually a plus or minus for society. We regularly forget what our grandmothers used to tell us, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson are especially noteworthy for their “good intentions.” Neither was a proponent of slavery at a time when virtually all their peers were advocates for, as Lee put it, “a moral and political evil.” The most honored man in their youth, Thomas Jefferson, wrote eloquently about freedom but kept dozens of slaves at his plantation, Monticello — today a World Heritage site.

“In my schoolboy days I had no aversion to slavery,” the father of American literature, Mark Twain, wrote three decades after Lee’s death. ”I was not aware that there was anything wrong about it. No one arraigned it in my hearing; the local papers said nothing against it; the local pulpit taught us that God approved it, that it was a holy thing, and that the doubter need only look in the Bible if he wished to settle his mind — and then the texts were read aloud to us to make the matter sure; if the slaves themselves had an aversion to slavery they were wise and said nothing.”

In that climate, both Lee and Jackson decided that loyalty to their home state, Virginia, was the greater good and, of course, fought for the Confederacy. No one doubts that they fought honorably while few, if any, historians claim they ever treated a black man, woman or child with anything but kindness. The record of neither man contains anything like that of General Nathan Bedford Forrest whose troops apparently massacred black Union prisoners at Fort Pillow.

Highly religious, Stonewall Jackson, became a slave holder, history tells us, only because several members of his illegal school for blacks begged him to buy them. He had started the Sunday school on principle, and indeed in direct violation of Virginia law, because he believed, as Lee did, that the true road to emancipation came through education. Lee’s anguish at deciding whether to back Virginia or take command of all Union forces is famous.

Today, it’s obvious Lee made the wrong decision. But it wasn’t clear to anyone in 1861. Even the great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, thought blacks were genetically inferior to whites; the brilliance of escaped slave Frederick Douglass being the “exception that proved the rule.”

Blacks today have solid grounds for despising the 1960s myth that “the South shall rise again” and have even stronger grounds for hating the symbols of racism, like the so-called Confederate flag. The reality of what happened all those generations ago was buried by the purveyors of pre-civil-rights hate but, like humans of all generations and cultures, this post-civil-rights generation should be cautious about “throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

Lee and Jackson were wrong to fight connected with any concept of slavery. But right or wrong, how ironic that today when the whole world bemoans the intentional destruction of the Giant Buddha Statues of Afghanistan and the dynamiting of a half-dozen World Heritage sites in Palmyra, Syria we – in tiny Charlottesville, Va. — are considering eradicating “history” because the past’s version of it might be flawed.