Poor University of Virginia. The College of William & Mary hogged the glory among progressives when Katharine Rowe, W&M’s new president, gratuitously inserted herself into the Ralph Northam blackface controversy by uninviting the governor from attending the annual celebration of the university’s 1683 founding.

Responding to news of the racist image in Northam’s 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook, Rowe announced four days ago, “That behavior has no place in civil society – not 35 years ago, not today. It stands in stark opposition to William & Mary’s core values of equity and inclusion.”

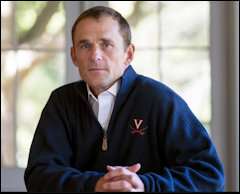

How, oh, how could UVa signal its virtue as well? UVa’s newly installed president, James Ryan, had no event from which to retract a gubernatorial invitation. I have an idea on how UVa could make a useful contribution to the controversy, which I’ll get to in a moment. But Ryan opted for expressing his politically correctness in an open letter to the Board of Visitors and the university community:

… This has been a sad and bewildering time for the Commonwealth. The photo circulated the other day was shocking and racist, no matter who was in it. This community knows all too well the pain and hurt that can come from reopening wounds, many of which remain to be fully healed. It is clear that this photo has deepened those wounds for many people in our community, the Commonwealth, and beyond, and it is equally clear that the photo is antithetical to the values of our community.

Over the past year, I have come to know Governor Northam as a decent and kind man, with an admirable record of service to our Commonwealth and the nation. But I also believe that any leader—at any level—depends on the trust and support of the people he or she represents. If that trust is lost, for whatever reason, it is exceedingly difficult to continue to lead. It seems we have reached that point.

Regardless of what happens and when, it is my hope that this painful episode will underscore the need to continue the conversations begun here and elsewhere in the Commonwealth about our past and the ways in which it continues to influence our present. I hope as well that it will underscore the importance of continuing to do all that we can to ensure that our community is one based on equal dignity and mutual respect.

So, a 34-year-old photo has deepened wounds, is antithetical to university values, and has undermined Northam’s ability to lead. Therefore…. what? Ryan didn’t join the call for Northam’s resignation. There was absolutely no point to this missive other than to signal his opposition to racism, which was never in question to begin with.

What the letter signifies to me may not be what Ryan intended: (1) He’s willing to join the condemnation of Northam before all the facts are in; (2) Northam’s “admirable record of service” doesn’t outweigh an incident (of as-yet uncertain nature) from the distant past; and (3) we can expect more virtue signaling from UVa’s president in the future.

How UVa can contribute to the debate. If Ryan wants to inject himself into a debate, he can make a useful contribution. He could direct his cadre of researchers digging into the history of race and racism at UVa and Virginia to develop a comprehensive history and timeline of blackface. A key question swirling around the Northam blackface scandal is the extent to which college students dressed in blackface back in the 1980s and the degree to which the practice was considered odious. When judging Northam’s actions 35 years ago, context matters. UVa can provide that context.

- How frequently did students at UVa and other Virginia institutions dress up in black face back in the early 1980s?

- When did progressives begin to focus on the use of black face as offensive to African-Americans, and how widely accepted was their point of view in 1984?

- What policy, if any, did the University of Virginia and other universities, both in Virginia and nationally, have toward black face in the early 1980s? Was the practice banned? Was it even an issue that concerned college administrators?

- What meaning did students attach to black face? Was it an expression of hatred and contempt, or were students just oblivious to how African-Americans might react? Did students think of dressing up in black face and KKK costumes as a lark? Or was it deliberately transgressive: a statement of rebelliousness against emerging norms and politically correct authority?

- To what extent did black people care about the issue in 1984? Did they slough it off as the antics of immature white kids? Did they silently resent it? Did they mobilize to attack the practice? When did the practice come to be defined as “deeply wounding?”

UVa can inform the debate over Northam by providing background that tends to be forgotten when people project 2019 values onto 1984. Whether Ryan is interested in providing context, which may or may not support the rush to condemn Northam, is an open question. How he follows up on this incident will reveal much: Does he want UVa to explore all aspects of the past as the university “continues the discussions” about race, or just the leftist narrative?