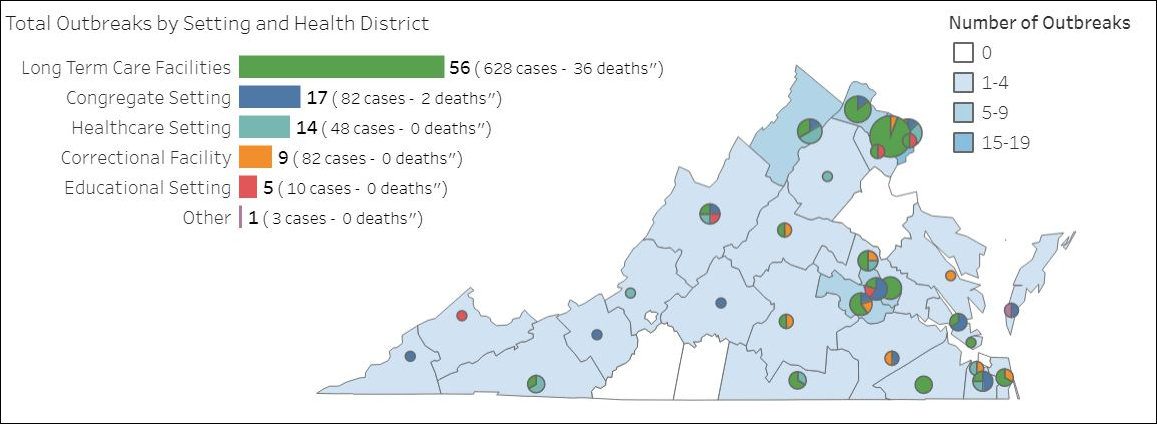

Among the useful new data sets published by the Virginia Department of Health on its COVID-19 dashboard is a map of “outbreaks” around the state. The dashboard does not define an “outbreak” but it appears to entail cases in which multiple infections are traced to a particular location. To no one’s surprise, long-term care facilities top the list. But “congregate settings” (apartments, businesses, churches, etc.), hospitals and correctional facilities figure prominently as well.

This is a useful way to look at the data. If we want to tamp down the spread of the virus, it makes sense to focus on limiting the number of outbreaks by such means as canceling events, limiting the size of gatherings, and shutting down certain categories of business. Adopting this perspective also allows us to call into question some social-distancing measures, such as chasing a father and daughter off the beach (see Kerry Dougherty’s column, “No More Sand Castles“).

Fighting COVID-19 requires the balancing of competing values: protecting the public health versus safeguarding our individual liberties. One way conceptually to approach this balancing act is to distinguish between measures that significantly reduce public-health risk and measures that provide an insignificant diminution of risk. Controls designed to prevent the spread in nursing homes, full of vulnerable old people, yields a much higher social benefit than, say, shutting down the service of a Chincoteague church where 16 parishioners were sitting at safe social distances from one another.

In the media frenzy over COVID-19, we seem to have lost sight of the original purpose of social distancing — to “flatten the curve,” or spreading out the incidence of the disease over time, to avoid overwhelming our hospitals, rather than allowing the epidemic to spike. The downside to the flatten-the-curve strategy is that, by stretching out COVID-19 infections over many months, it prolongs the shutdown of the economy and the insults to individual liberties.

The important thing to remember here is that the spread is inevitable until such time as the pharmaceutical industry can mass produce a vaccine, which most likely will not occur until mid-2021, or the population develops herd immunity after enough people recover and develop resistance to the disease. Most people are going to get the disease no matter what. The only question is whether they get it all at once or over an extended period of time.

The evidence suggests that social isolation is working. We are stretching out the spread over time. The epidemic may be close to peaking in Virginia. (See John Butcher’s graph here.) Our hospitals are nowhere near running short of hospital beds, intensive care units, or ventilators. They prepared for the worst, and they have capacity to spare. (The scarcity of personal protective equipment is still an issue.)

Accordingly, we can begin contemplating the easing of social-distancing controls without fear that our hospitals will relive scenes from China and Italy. The trick is to maintain high-benefit controls on conferences, concerts, nursing homes, correctional facilities, and non-critical businesses while dialing back the low-benefit controls. That’s where the “outbreak” map comes in. For the moment, we should continue to focus policy on halting outbreaks. But it is folly to pursue zero risk. We need to relax our grip on low-risk activities. We need to tolerate low-risk interactions, even if it means a small number of people contract the disease who would not otherwise.

Speaking conceptually — the devil is always in the details — we should rank all social-distancing measures by the level of risk they reduce. As we progress through this crisis, we should endeavor to work our way up the list, maintaining measures that achieve large risk reduction and dialing back those that offer low risk reduction.

Likewise, we should allow people who have recovered and have developed antibodies against the disease to be exempt from social-distancing controls. Some small percentage may get re-infected, but those should not stop us from liberating these people from their shackles. While the risk they pose is not zero, it is low. We need to let them get back to work and living life.

Under our federal system of government, those decisions rest with the states. Here in Virginia, Governor Ralph Northam, who has declared a state of emergency, calls the shots. As evidence mounts that the epidemic has peaked, citizens should press him to start rolling back emergency measures one by one as prudence dictates and expedite the return to normal.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.