by James A. Bacon

Joe Herbin has always been a hard worker. When he was 15 years old, he’d accumulated the $1,200 it took to buy an old Cadillac. The fact that he didn’t have a driver’s license — or was too young even to get one — wasn’t a deterrent. He installed a bad-ass sound system and drove around town like the king of the world for about a week, then had an accident in a gas station. The policeman gave him tickets for about four different violations — the first of many to come.

Herbin kept driving, though, and he kept racking up tickets in and around the City of Richmond, often while driving to or from work at Wal-Mart, Target or his cousin’s music CD shop. He prayed every day that he wouldn’t get stopped and slapped with another fine, penalty or gig in jail. He was around 22 years old when he was driving his pregnant girl friend to the hospital, when he got stopped again. This time someone finally told him about the Drive to Work program, a not-for-profit group dedicated to helping people with suspended licenses restore their driving privileges so they can function as productive members of society.

When Drive to Work staff tallied up all the fines, penalties and back interest, they found that Herbin owed a total of $7,500 to courts in five jurisdictions, each with its own set of procedures for collecting the money. By his own admission, Herbin is a “careless person,” lacking the temperament to make payments to so many court clerks on a regular basis. Drive to Work created a plan whereby he made a single monthly payment of $357 to the non-profit, and staff made sure each court clerk received the money on time. Drive to Work also negotiated a deal allowing Herbin to receive a restricted driver’s license allowing him to drive between home and work, home and church, and home and daycare.

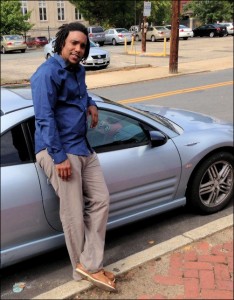

Today, Herbin has worked his fines down to under $1,000 and his monthly payments to less than $50. He now drives a forklift for Frito-Lay making $17 an hour, as well as a part-time job for extra cash, and he lives in a committed relationship with the mother of his three children.

Herbin’s story is surprisingly common in Virginia. A recent study conducted of 606 of Drive to Work’s clients found that fines, penalties and interest ranged as high as $33,000, with average debt about $4,800. Clients owned money to an average of 3.6 different courts.

At an awards and recognition banquet Monday, Drive to Work President O. Randolph Rollins described the predicament of another client. Of the $8,000 in obligations he’d amassed, 35% consisted of unpaid fines, 45% of court penalties relating to hearing his case, and 20% interest.

The system creates a vicious cycle for poor and working class people who build up fines they cannot hope to repay, Rollins said. Many continue driving because they can’t get to work any other way, lose their license and lose their jobs. The situation is a Catch 22: Without work, they have no hope of generating earnings to repay the fines. Indeed, the inability to repay fines accounts for 37% of all suspended licenses in Virginia, Rollins said — affecting nearly 200,000 people across the state.

Recognition of the need to restore drivers licenses became a political issue during the McDonnell administration and with bipartisan support has continued during the McAuliffe administration. The Department of Corrections has implemented a program to help felons prepare while still in prison to get their licenses when they re-enter society. And Del. Manoli Loupassi, R-Richmond, submitted a bill in the 2015 session to study the use of drivers license suspensions as a collection method for unpaid court costs. Although that bill failed because of a technicality, said Rollins, there strong support for passing it next year.

The initiative to restore driving privileges is part of a larger movement to reintegrate felons into society upon their release. The days of giving an offender $20 and bus ticket home are long over. Virginia has one of the best track records in the country for recidivism, said Harold W. Clark, director of the Department of Corrections. Second only to the state of Oklahoma, the recidivism rate is just under 23%. The rate ranges as high as 60% in other states.

While the biggest risk factors for recidivism include antisocial personality, antisocial associations and dysfunctional family, the ability to find employment is one of the “top eight,” Clark said. “Not having a driver’s license is a serious problem. People without driving privileges are effectively excluded from many jobs.”

Many offenders don’t know why their license was suspended or how to get it back, said Clark. A program like Drive to Work helps them navigate the bureaucratic maze, create plans for repaying fines and get offenders a license, even if just a restricted one, that allows them to seek employment.