by Asra Q. Nomani and Debra Tisler

Late Wednesday afternoon, in Courtroom 4B of Arlington County’s Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court, Sean Jackson beamed widely as a judge granted him and his parents, Carlos Makle and Kim Jackson-Makle, joint custody of Sean’s baby girl, Amoria, instead of relegating her to foster care or instability with a mother struggling with drug addiction.

Kim later said, “Hallelujah,” thinking the nightmare they had been living for over a year with the County’s inept Division of Child Protective Services was finally over. But it was just about to begin all over again. Arlington County’s Child Protective Services was about to dispatch a social worker to an apartment in Arlington to seize Amoria’s second cousin, London, also a cute baby girl, from her mother, Paris Adams.

Why?

Over an alleged missed dosage of Tylenol Wednesday morning that the baby wasn’t even required to get, per doctor’s orders, but was rather prescribed “as needed.” With so much written in the news about public policy, legislation and politics, this story is disturbing because of the sheer inhumanity of bureaucrats operating with complete disregard for actual child welfare or a mother’s heartache.

First, a rewind.

As chronicled in an investigative reporting piece, “Fathering While Black,” which we published this past December, Kim’s family had been navigating a living hell since early 2022 when her son, Sean, first started fighting in Courtroom 4B for visitation with his daughter. Despite having a clean record, a steady job as a paramedic, and a stable home in which his parents were already approved foster and adoptive parents, Judge Michael Chick and Amoria’s court-appointed attorney, Karen Keys-Gamarra, kept returning the baby girl to her mother, a young woman struggling with drug addiction. They never got the mother the help she need — it was as if they were setting the mother up to fail. Twice, Keys-Gamarra even called the baby’s father “retarded,” although he has no cognitive issues. (She denies it.) It was a word she had also used in a hot-mic moment in her role as a Fairfax County school board member. Judge Chick, who once competed on “America’s Ninja Warrior,” went along with Keys-Gamarra’s bullying of the family.

Finally, in late November, after the baby was discovered to have cocaine in her body after being with her mother on Thanksgiving Day, the father and grandparents got temporary custody, but not for long. In early December, Judge Chick issued a shocking order that allowed a Child Protective Services officer from Arlington County to arrive unannounced at the family’s home in Stafford County with local sheriff’s deputies, and grab the baby.

“They took my baby!” Sean wept that night, stunned and devastated.

The family did what so many families have to do in this warped system that has become America’s “child welfare” bureaucracy. They sucked it up and appeared in court, armed with exhibit after exhibit, proving their stability as a family. There, they saw a new face in the courtroom: attorney Jason McCandless from the local prosecutor’s office for Arlington County. In a fancy tweed suit, he was arrogant, derogatory and flippant, taking a table in the front of the courtroom, while the mother took another table, relegating the father and his family to the spectator seats. He had signed the request for the court order seizing Amoria from her family.

In child welfare circles, unbeknownst to Amoria’s family, McCandless was kind of notorious, going back to 2011 when the Washington Examiner published explosive investigative reporting accusing him of being involved in, quite literally, “Baby Snatching.”

In an opinion piece, columnist Barbara Hollingsworth argued a federal judge should hear a lawsuit filed in Alexandria federal court on behalf of eight children placed in foster care by Arlington County. She wrote:

The list of serious accusations contained in the lawsuit against DJR Judges George Varoutsos and Esther Wiggins, Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney Jason McCandless, and various Arlington CPS officials is long: perjury, RICO violations of civil rights, fraud upon the court, obstruction of justice, unconstitutional “ex parte” hearings, court orders that were never served, depriving parents of their due process rights, “missing” court orders, illegal searches and seizures, and felony removal of documents from court files, to name just a few.

One accusation rang true in Amoria’s case and another one that hit close to home for Kim: depriving parents of their due process rights.

In early 2022, McCandless drew headlines for his callousness in the case of an out-of-town mother, Beatrice Rivera. The lawyer had been instrumental in fighting to get custody of her son, who had autism and had fled several times when he experienced sensory overload. McCandless won. The mother lost. She is still fighting to get her son back.

Against Kim’s son, Sean, McCandless was armed with one document: the article we had published, “Fathering While Black,” and he was angry. He denounced the publication of the article and, more concerned with the spotlight on the case, he forgot the topic at hand: the welfare of the baby found with cocaine in her body not long before. He complained again and again about the grandmother and son posting updates on TikTok and Facebook to their family and friends about the trauma they were experiencing as a family.

Did we mention that Amoria’s family is Black and McCandless and Judge Chick are White? And the foster mother that baby Amoria was sent to was also White. In seeking justice, race shouldn’t matter. But here it becomes an issue because McCandless and Chick seemed to forget any “diversity, equity and inclusion” lessons they have learned, constantly diminishing this family and dis-empowering them in their advocacy for their beloved Amoria. McCandless’ and Chick’s behavior was reminiscent of the way that White slave owners historically treated many of their Black slaves, separating them cruelly from their children. It was so traumatizing for those children of slaves that abolitionist Frederick Douglass said he couldn’t even weep at his mother’s death because the slave owners hadn’t even allowed him to know his mother, Harriet Bailey.

Douglass said: “Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.”

The prejudices of these modern-day powerbrokers couldn’t overcome one fact that emerged again and again in the weeks that followed: the mother’s drug use. Finally, in a relief beyond ordinary relief, the grandparents and father won joint legal and sole custody of Amoria.

That is how we land at Wednesday afternoon, Kim back at home, feeling like a ton of bricks had been lifted off her shoulders.

London bridges

Then, at about 5 p.m. yesterday, Kim’s phone rang. A young mother was weeping on the other end of the line.

Little Amoria has a second cousin on her maternal side, London, also a beautiful baby girl, and Kim had gotten very close with London’s mother, Paris Adams, over the past year. Paris is the first cousin of Amoria’s mother.

After Paris gave birth to London last fall, the young woman had landed in the crosshairs of Arlington County’s Child Protective Services after she had gotten into an altercation with a man with whom she had once had a relationship. Unlike her cousin, however, Paris was doing everything right by Child Protective Services. She was drug-free. She had gotten a lovely studio apartment in Arlington and scored a job in the deli of a local Giant, making $12 an hour. She would awaken at 4:35 a.m. with her baby girl to get her to day care before reporting to work at 7 a.m.

Paris had a dream to open a store selling exotic fish — a passion of hers — but, for now, she was happy making a living cutting turkey slices for customers. Her mother was helping her care for an older son, Roman, six. Paris was like a magnet for troubled men, and she had first run into McCandless when someone had called Child Protective Services worried about Roman. In that case, McCandless removed Roman from Paris and placed him with her mother. Paris didn’t lose her parental rights. And she was getting on track with plans to reunite her family.

About two weeks ago, she had had another run-in with McCandless. At a hearing again in Courtroom 4B, McCandless lavishly praised the mother for doing a great job raising her baby and then, to the shock of everyone in the room, he told Judge Chick that he wanted to seize the baby from Paris because the County couldn’t “afford” to have the baby stay with the mother. Even the judge was dumbfounded.

Judge Chick said: “My mouth just dropped open. You want to take the baby from the mother?! I’m disappointed in the State. How can you say all these positive statements about the mother and then take the baby from the mother?!”

Paris’s attorney also protested. Judge Chick denied the motion. McCandless flung his court documents across the table, angry.

Paris laughed in shock and said aloud to McCandless: “You’re really angry, aren’t you?”

In recent days, London had gotten sick and Paris had dutifully taken her to the doctors. She got clear instructions about how to manage London’s fever: give her Tylenol every three hours — AS NEEDED.

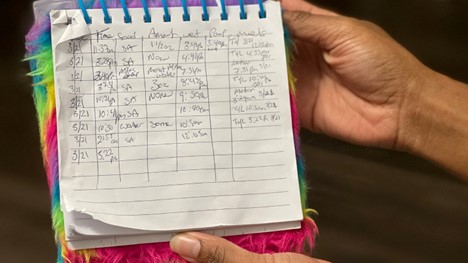

Ever since London had been born, Paris has kept a log religiously with details about the baby’s feedings, any temperatures, bowel and urinary movements, and other important details. It made hand-offs with her mother easier and helped her answer questions from physicians and others quickly and authoritatively.

So, she knows that she awakened London at 3:24 a.m. and gave her a dose of Motrin. But London was sleeping so soundly and her temperature was down at 6:40 a.m., so Paris chose to not give her baby Tylenol again. That is wise, according to the National Institutes of Health and other agencies, which warn against giving babies unnecessary dosages of Tylenol, saying very clearly that too much Tylenol can negatively impact a baby’s brain development. Paris was just happy her baby’s temperature had eased.

At 10 a.m., Paris had a scheduled visit with a Child Protective Services social worker, Shenee Wilson. It started off poorly when Paris politely asked if the staffer would remove her shoes. “They’re new shoes,” said the worker, missing the point.

Paris shrugged it off and thought she’d just use her Swiffer quickly afterwards on the floors. Then, things got prickly when the worker kept peppering Paris about not giving her baby another dose of Tylenol at 6:40 a.m. Paris tried to explain her position but felt like she was talking to a brick wall.

The worker finally left. Paris called another social worker to explain her decision-making and thought all was settled.

Then at 5 p.m., there was loud pounding at the door.

Snatch-and-grab

When Paris opened the door, she was shocked to see a social worker, Maggie Marshall, with an Arlington County police officer, Officer Keating, badge No. 1736, both White.

“We are here to take custody of your baby,” the social worker said.

On her LinkedIn profile, Marshall writes: “My mission as a social worker is to enhance individual and societal well-being by empowering and engaging clients, protecting and promoting human rights, and advocating for policies that would remove barriers for those in need, oppressed, and living in poverty to achieve their full potential.”

She was doing exactly the opposite.

“What?!” Paris exclaimed, confused, frightened, and traumatized all at once, seeing two authority figures in the hallway, trying to take her baby.

“Where is the removal paper?” Paris asked.

The police officer said, “Paris, don’t make this any harder on yourself.”

Over the next several minutes, the social worker left the apartment ransacked. London’s medical records were quickly photographed and then tossed aside. The drawers with her clothes ransacked and left open, a Target plastic bag tossed to the ground, a mother devastated and a baby weeping. It was cruel, unnecessary, and callous. Paris tried to ask questions and was rudely dismissed. She fell to the floor with her baby in her arms, trying to reassure her, “Mommy’s going to get you back. I promise.”

The social worked offered her little comfort, saying, “I disagreed with this decision. I will help you every step of the way to get your baby back.”

If she disagreed, Paris wondered, why was she going along with this “child welfare” charade? Who was behind this intrusion? Was it McCandless? He had just lost control of Amoria. Was London next? Was it Judge Chick?

Paris had no answers because the social worker gave her no court order. None. Zero. Zilch. All she did was place a slick brochure on Paris’s bed, “Child Protective Services: A Guide to Investigative Procedures.”

Paris tried to hand her logbook to the social worker. Marshall wouldn’t take it. Paris tried to give her London’s bottled water. The social worker wouldn’t take it.

She changed London’s outfit twice.

The social worker told Paris to move faster. The police officer actually scolded the social worker: “Look I don’t have any children but this would be devastating if this happened to me. She is hurting. And she is compliant. Give her a break.”

Paris didn’t want to be compliant. She wanted to scream. “I’m not a runner,” she said later, but the social worker and the police officer, shadowing her every move, were treating her like a criminal.

She called her mother. And that was when she called Kim Adams on FaceTime. Kim had just gone through this painful, gut-wrenching experience. She couldn’t believe she was witnessing it again.

“Is she going to a White couple?” Kim asked. She had gone through this before. When Amoria was taken from Sean, she also landed in the hands of a White family.

The social worker asked Paris if she would be too ashamed to go outside with her baby. Paris looked at her incredulously. She didn’t care what anyone thought of her. She would stay with her baby every second she could. They walked through the hallway and into the parking lot. It was a walk of shame. Everyone from the rental office watched, confused as to what was happening. At the official Arlington County car, a white four-door Chrysler, Paris placed London in the car seat. She tried to burp her but the social worker wouldn’t let her do it.

And then they told her to step away.

Step away from her baby. Paris was losing her baby over a dose of Tylenol that she wasn’t even required to give her.

On a stranger’s chest

Back in the apartment — alone — Paris wept. She put the last onesie that London had worn up to her face to breathe in her scent. She studied her logbook. Had she done anything wrong? She hadn’t.

She left the apartment just as the social worked had ransacked it in order to document this experience that felt like a home invasion.

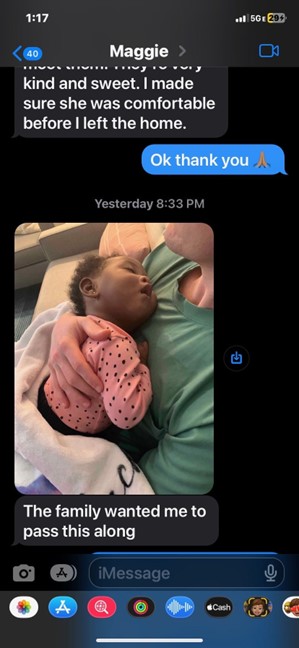

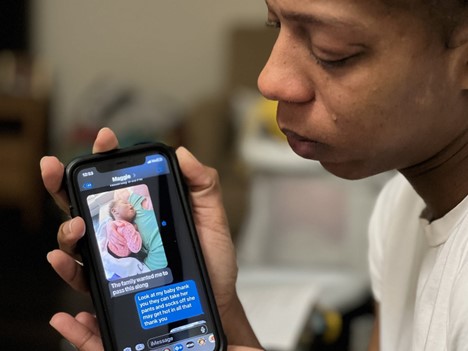

She got a message that her London was in the care of a couple, Zac and Victoria. Then she got a photo of her baby girl with the message: “The family wanted me to pass this along.”

She was horrified. Later, she went on FaceTime with a friend and studied the photo together, her own image in the FaceTime ironically separate from her daughter but watching over her. London was lying on the chest of a stranger — a man whom the baby had never met before — with stubble on his chin and manicured nails. He hadn’t put a clean cloth over his chest for London to lie upon, as she had requested. London’s head was swung back, her mouth open, as if she were gasping for air. He had London sleeping on her arms, something Paris was mindful not to do to keep her arms from falling asleep too beneath her little weight. It was not a reassuring photo.

She wanted to scream. But she had to suck it up to get her baby back. Instead, she wrote: “Look at my baby,” with tips on how to make her more comfortable.

If she could speak to Gov. Glenn Youngkin, Paris says she wants two things: her baby back — and an investigation.

“This is a snatch-and-grab,” says Paris. “I feel empty. But I will get my baby back.”

The man in the photo holding London is White. It shouldn’t matter but it does. Child Protective Services in Arlington had stolen Paris’ Black baby girl away from her — a Black mother — to put the child in the hands of white couple. This happened in an era when justice means that such assertions of racial power and privilege were not supposed be happening anymore.

But they were happening — and they are — because in a first floor apartment in Arlington, a young mother is pacing right now, wondering how to fill the emptiness that is in her heart with the baby who should be in her arms.

Morning

In the morning, Paris spoke to the social worker. London was sleeping. Her temperature was 98.7. The foster parents were giving her Motrin.

“Why?” Paris said. “It’s their way of putting her to sleep.”

Paris asked again for a court order. The social worker still didn’t have one for her.

London hadn’t gone to sleep until midnight. She woke up at 2 a.m.

“My baby is looking for her mom,” Paris wept.

When Paris talked to London’s pediatrician, she confirmed that she had told her to pause the Tylenol and Motrin if the fever fell. The physician herself started crying.

“My heart is broken for you,” she said.

Paris was getting a video visit at 1:30 p.m. with London.

CALL TO ACTION: Please contact these leaders to take action to reunite London Adams with her mother, Paris. A baby was taken from a mother without due process.

1. Virginia Lieutenant Gov. Winsome Sears, ltgov@ltgov.virginia.gov

2. Virginia State Sen. Louise Lucas, district18@senate.virginia.gov

3. Department of Social Services Commissioner Danny Avula, Danny.Avula@dss.virginia

4. Please copy asra@asranomani.com and debra.tisler@gmail.com

Asra Q. Nomani is a former Wall Street Journal reporter and senior fellow at Independent Women’s Network. She is the author of a new book, “Woke Army.” Debra Tisler is the founder of Emergent Literacy, a nonprofit dedicated to advocacy for children and parents. Contact them at asra@asranomani.com and debra.tisler@gmail.com. They can be found on Twitter at @AsraNomani and @Debra_Tisler.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.