Now that Democrats have de-confirmed Virginia’s state health commissioner, Colin Greene, they have effectively set a new qualification for the office: it is no longer permissible to express skepticism that “systemic racism” is, in the words of Sen. Jennifer McClellan, D-Richmond, “a public health crisis.”

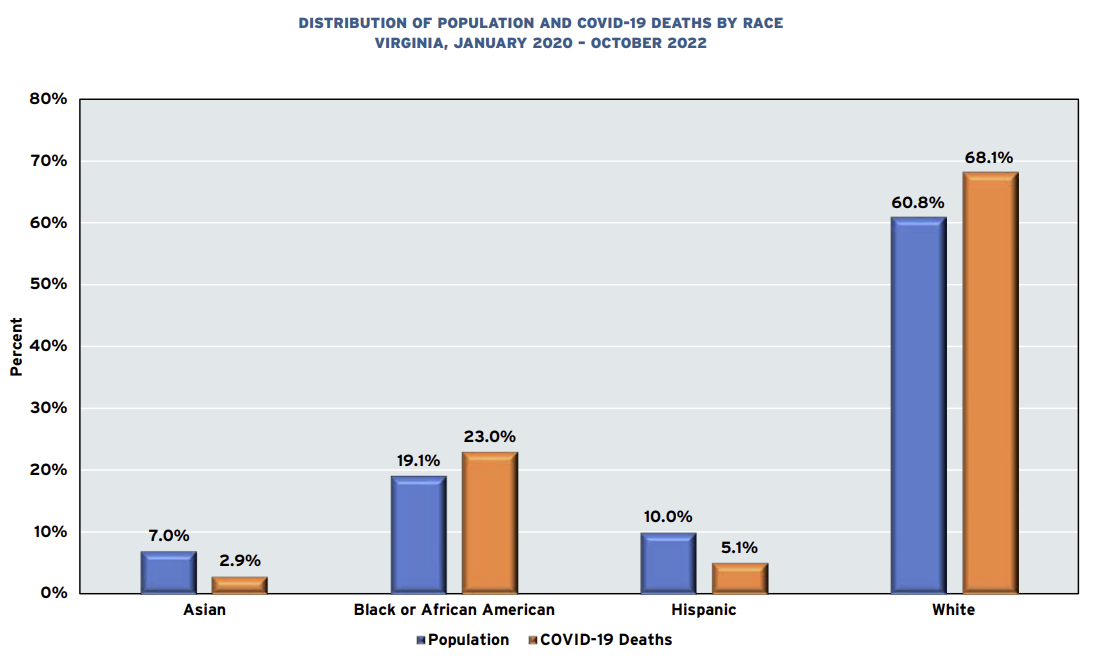

Ironically, only a few days after senate Democrats sent Greene packing, Old Dominion University has published a graph in its 2022 State of the Commonwealth report that dismembers any idea of systemic racism playing a role in the biggest public health crisis of our generation — the COVID pandemic. The graph above, taken from the study, compares the percentage of COVID-related deaths for each race to its percentage of Virginia’s population.

African Americans accounted for 23% of COVID deaths through October 22 compared to only 19.2% of the state’s population — a four-percentage point gap.

But it turns out that Whites accounted for 68.1% of COVID-related deaths compared to 60.8% of the population — an eight-percentage point gap. Is that evidence of systemic anti-White racism?

Wait, there’s more: Hispanics, also alleged to be an oppressed “people of color,” accounted for 5.1% of COVID deaths compared to their 10% of the population. And Asians, also classified as an oppressed “people of color” (although sometimes described as “white-adjacent”) accounted for 2.9% of COVID deaths in Virginia compared to their 7% of the population!

(Let me pause to state that Old Dominion University does not cite this data to make the arguments that I am making.)

The Northam administration was obsessed by racial statistics during the pandemic, fretting that Blacks and Hispanics in particular were not getting their proportionate share of masks, COVID tests and, later, their proportionate share of COVID vaccines.

It was obvious to some of us at the time that the Northamites were fixated on an extraneous factor — race — when they should have been focused on medical risk characteristics such as age, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and weakened immune systems. Insofar as Blacks and Whites suffered disproportionately from those risk factors, they were disproportionately likely to expire from the virus, but their race had nothing to do with it.

Ironically, the Northam administration’s race-based initiatives had no discernible effect. The Governor made special efforts to ensure that Blacks and Hispanics got their share of tests and vaccinations, but the health outcomes between the two groups differed dramatically. If Northam’s actions to combat the disease had made one whit of difference, Blacks and Hispanics would have departed from the statewide norm in the same direction, not in diametrically opposite directions.

The logic of the “anti-racists” — that differential outcomes reflects racism — would obligate us to conclude that Virginia healthcare is “systemically racist” — against Whites and Blacks and in favor of Asians and Hispanics. But that would be nonsensical. That leaves us with the proposition that the healthcare system is largely color blind and that different COVID outcomes reflect variations in the risk factors found in each racial population, which in turn likely arises from socioeconomic, educational, cultural and other factors.

Unfortunately, the state health department doesn’t break down COVID metrics by socioeconomic status or educational level, much less cultural attributes, so the influence of those factors on outcomes has received almost no analysis.

Still, we can confidently say that the “anti-racist” ideology asserting “systemic racism” in healthcare receives no support from the COVID data. When there is little disproportion in the rate at which Blacks and Whites suffer COVID fatalities and when Hispanics and Asians die at much lower rates, something else is going on. Forcing square pegs into round holes cannot possibly be helpful in understanding the dynamics of the pandemic, or any other public health issue, and can lead only to mis-spent efforts.

James A. Bacon is executive director of The Jefferson Council. The views expressed here are entirely his own, not those of the Council.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.