The commonwealth of Virginia lacks the fiscal resources to maintain and upgrade its transportation system, argues Bob Chase, president of the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance, in the latest issue of the Virginia Newsletter. There’s nothing surprising about his conclusion — he and others have been making essentially the same arguments for a long time. What Chase accomplishes in his essay is to explore the topic in greater depth than is possible in a typical op-ed column and to update his argument with the latest state data.

Maintenance expense is eating up a larger percentage of available funds and, even then, road conditions are deteriorating year by year. Federal stimulus funds are expiring. Virginia has finite capacity to issue transportation bonds. Public-private partnerships, while promising, are suitable only for large, complex and toll-driven projects. The federal government will permit only limited tolling of federal highways. Meanwhile, long-term growth trends will put the transportation network under increasing strain.

That much is beyond dispute. But Case also advances an argument for “new, sustained, long-term transportation funding” — in other words, higher taxes. Options include increasing the motor fuels tax, raising the sales tax, hiking the motor vehicle sales tax, imposing a Vehicle Miles Traveled tax, and, harder to sell politically, raising the state income tax. No one likes paying taxes, he argues, but the failure to address intensifying traffic congestion imposes costs such as time spent in congestion and lost economic growth that are even more onerous.

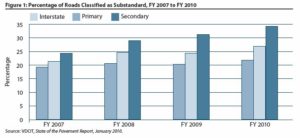

As I have argued repeatedly on this blog, Virginia is not spending enough on its transportation system. The mounting backlog of maintenance needs (shown in the chart at right, taken from the newsletter) means that our roads are getting in worse shape as time goes by. The McDonnell administration is addressing that problem in the short run by accelerating the outflow of unspent dollars that had accumulated excessively during the recession. Road conditions should show improvement this year. But the long-term trend is dire. We need more money, but none of the means for getting it are very popular.

That’s a key topic that Chase did not address. In 1986, Virginians trusted Gov. Gerald Baliles to spend the money well when he raised the motor fuels tax and sales tax to current levels. They don’t trust Virginia’s political establishment to spend the money wisely today. People belly ache about potholes and traffic jams but for all the talk about the cost of congestion and lost economic opportunities, the average citizen just doesn’t see the benefit to higher taxes. And there are very good reasons for that.

First, the cost of congestion is higher for people who perceive their time as more valuable — mainly higher-income Virginians and companies for whom transportation and travel is a cost of doing business. That’s why business lobbies have consistently endorsed higher taxes as a means to “get Virginia moving,” to borrow a phrase from Gov. McDonnell. Trouble is, they don’t want to pay for the roads in proportion to which they would benefit from them. They want the general public to pay. And that’s a hard sell.

Second, money isn’t funding projects that benefit the general public. The Charlottesville Bypass is a classic case. The Virginia Department of Transportation is spending $245 million to build a bypass designed mainly to accommodate freight traffic passing through the Charlottesville-Albemarle area. That expenditure for a 6-mile bypass will do very little to alleviate congestion for the people actually living there. It’s not clear how other expensive mega-projects in the works, from the U.S. 460 upgrade of the Coalfield Expressway, will help the average Joe either.

Third, there is no system for ranking projects, big or small, on a Return on Investment basis. The paucity of objective metrics encourages people to think that projects are funded largely on the basis of political considerations, for the benefit of developers and other special interests. That’s not, in fact, always true. But sometimes it is.

Fourth, the McDonnell administration has not re-prioritized transportation projects in light of the 2007-2008 recession, which brought an end to the post-World War II growth patterns characterized by increasing indebtedness, Mass OverConsumption and “suburban sprawl.” A very strong case can be made that the United States is entering an era of infill and re-development driven by higher gas prices, changing demographics and the collapse of the housing boom. Yet projects in the state’s Six-Year Investment Program, conceived in a time when metropolitan areas pushed ever outward with scattered, low-density and disconnected development, have never been re-visited. In other words, higher taxes would address yesterday’s perceived needs, not tomorrow’s.

If the General Assembly raised taxes to fund more transportation projects, the administration would find a way to spend it. But spending more money on the wrong projects makes no economic or political sense.