By Steve Haner

While we await a decision by the State Corporation Commission on competing approaches for protecting consumers from unexpected offshore wind costs, some additional relevant information is worthy of notice. Two items call into question Dominion Energy Virginia’s refusal to assume financial risk for poor turbine performance.

Both items ought to make it easy for the utility to comply with an SCC-imposed performance standard of a 42% capacity factor. Yet it continues to balk. Since Dominion is not highlighting these items, here they are.

A few weeks back wind turbine manufacturer Siemens Gamesa announced test results for the 15-megawatt machine it is selling to Dominion for use off Virginia; it is among the largest now being built.

The press release claimed a record 24-hour power output of 359 megawatt hours, obviously for a period of optimal wind speed. Optimal wind speed doesn’t happen every day, of course, and some days there is no wind at all to produce power. But this new machine is capable of at least occasional 100% capacity output, which should make 42% capacity over time easy to promise.

The SG 14-222 DD turbine model has a 14 MW capacity, reaching up to 15 MW using the company’s Power Boost function. The model features a 222-meter (728-foot) diameter rotor assembly with three 108-meter (354-foot) blades, and a 39,000 square meter swept area. One blade is the length of a football field with end zones.

The second piece of positive data is continued steady performance from the two 6-megawatt offshore wind turbines Dominion installed two years ago. They achieved just under a 50% capacity factor through 2021 and the first nine months of 2022, based on reports to federal authorities.

Of course, two 6-megawatt turbines could not produce more than 8,640 megawatt hours in a 30-day month (8,928 in a 31-day month). That is their “100 percent.” The best performance months so far were February 2021 (74% output) and January 2021 (64% output.) The worst were the two months of August (22% in August 2021, 23% in August 2022.)

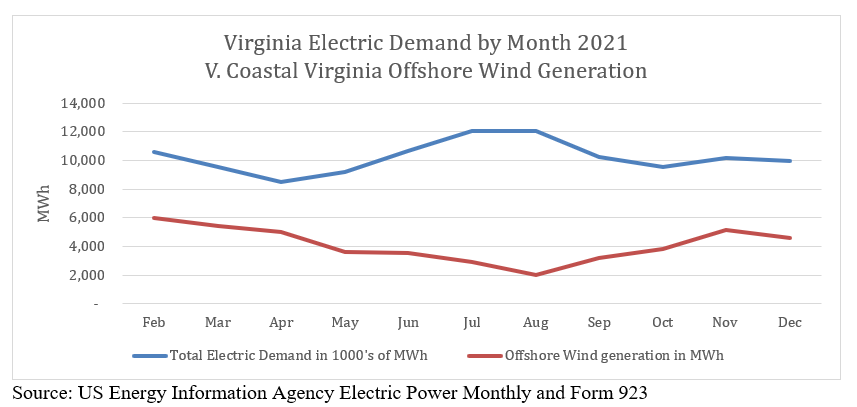

As the attached chart shows, the wind is best in the winter and least productive in summer, when the utility usually has its peak demand. The far larger full project, with 176 turbines capable of about 2,600 megawatts per hour (versus 12 in the pilot) is expected to follow that pattern. Of course, solar power peaks in the summer. (It is never intermittent, right?)

But again, having achieved 47% output in the first year and 48% during nine months of the second, what is the problem with a 42% performance standard on the full-size project?

David Stevenson of Delaware’s Caesar Rodney Institute compiled the chart and has also noted that when Dominion advocated for the two test turbines, it made broad promises about piles of relevant data they would produce. He can’t find it, especially hourly output data he’d like to see. But in a 350-page federal filing Dominion promised much, much more in exchange for federal taxpayer funding.

Or was research really the point? Perhaps not. Perhaps that 350-page document issued before the turbines were built was the extent of research in question, all we get. Perhaps more detail would provide some insight into why Dominion is not touting the Siemens Gamesa test data and the first 21 months of output from the two test turbines. There must be some reason Dominion has refused so far to accept a performance floor.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.