by Matt Hurt

Virginia’s system for accrediting public K-12 schools has engendered some concern since the release of school accreditation data on September 19. While students exhibited lower proficiency during the 2022 school year than in 2019, as measured by Standards of Learning test scores, the percentage of schools meeting the requirements for full accreditation barely budged.

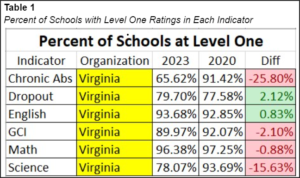

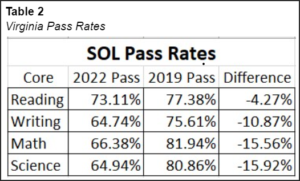

Table 1 below demonstrates the rates at which Virginia schools obtained a Level 1 rating (the highest available in our accreditation system) for each of the key metrics. Table 2 below displays the overall pass rates in Virginia for each of those content areas. (The English accreditation indicator is a composite of reading and writing results.)

Note that the English and math SOL pass rates dropped from 2019 to 2022, but Virginia schools didn’t realize similar declines in accreditation ratings. English (a composite of reading and writing) pass rates fell 4.27% but schools awarded the Level One accreditation rating increased 0.83%. Math SOL pass rates plummeted 15.56% but schools slid only 0.88%.

Why the disparity between student performance and school accreditation? Because schools are given accreditation credit when students show “progress” — even if they fail the SOL test.

In November 2017, the Virginia Board of Education updated the Standards of Accreditation. Some of the changes were positive: holding schools accountable for subgroup performance, and including a student growth statistic to be used in the calculation of the academic indicators.

The underlying logic of measuring student growth made sense. If a student failed the SOL test in that year but demonstrated growth over the previous spring’s score, the student was determined to have demonstrated growth and was counted as a pass in the school accreditation calculations.

The growth model implemented in 2018 was a wonderful thing. First of all, it was designed so a student earning any failing score in third grade could become proficient by no later than 7th grade. Second, it provided an incentive for schools to redouble efforts with their most at-risk students. Prior to this, students who were not expected to pass their SOL tests would be less likely to receive the extra intervention they needed to eventually be successful.

This growth model had some detractors, with most arguing that because the 3rd- grade tests set the baseline, there was no opportunity for 3rd graders to demonstrate growth. Some also argued that “learning loss” over the summer would mask the true gains made during the school year — if a student experienced “learning loss,” he or she really didn’t learn the material to begin with.

Fast forward to the 2021 General Assembly session, and the unanimous vote on HB2027/SB1357. These bills, signed into law on March 31, 2021, changed the spring-to-spring growth model to a through-year growth model.

The through-year model would track students’ growth from fall, winter and into spring when the SOL test is administered. All tests assess the same content. A student showing “growth” would score higher as the school year progressed.

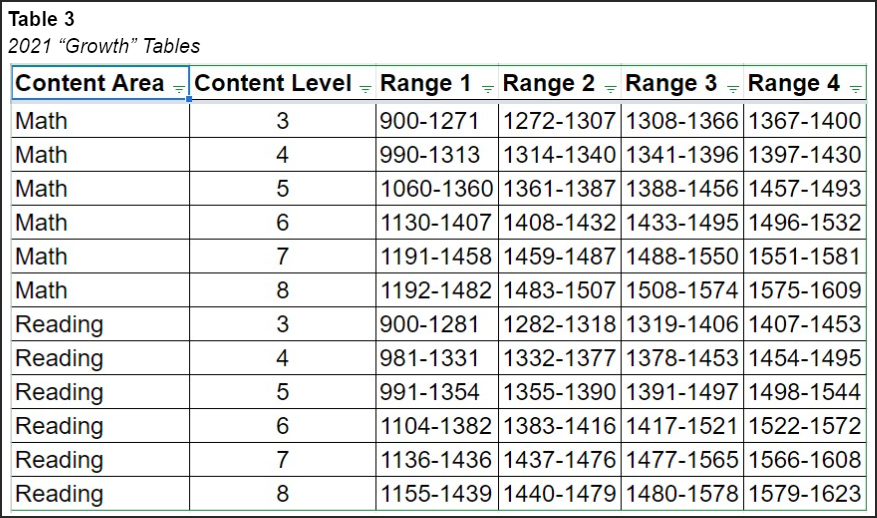

VDOE developed growth tables (Table 3) based on a new Vertical Scaled Score intended to communicate student performance throughout the year as well as from year to year. If students who failed their SOL tests managed to move their score from left to right on the table, VDOE determined that they had demonstrated “growth.”

Results

During the summer of 2021, educators in the Comprehensive Instructional Program consortium of mainly rural school systems invested far more treasure, blood, sweat, and tears in summer school than ever before in order to try to make up for lost time from the disruptions of that year. More students and teachers participated in summer school, more instructional time was allotted, and lower class sizes were facilitated. In the fall of 2021, we analyzed student level data by comparing fall 2021 growth assessment scores and spring 2021 SOL scores. On average, our students performed significantly worse on the fall test than the spring test. Therefore, we concluded, we either caused instructional harm to students during those summer programs, or the data we collected in the fall “growth” assessments was less reliable than we would like.

At the student level, an analysis of the data within our consortium revealed 3,335 students who passed their SOL tests in the spring of 2021 and failed the same content area in the spring of 2022. Of those students, according to VDOE criteria, 41% had demonstrated “growth.” That is correct: they were less proficient in 2022 than the previous year, and at the same time were deemed to have demonstrated “growth.”

Incentives, or Lack Thereof

The main problem associated with the new through-year “growth” model is one of incentives. There is no incentive for students to try their best in the fall, nor are there incentives to prod educators to ensure their students try their best. Please keep in mind that the fall test scores are used as a baseline in the determination for “growth,” so unreliable data in the fall will yield unreliable “growth” statistics in the spring.

In Virginia, students do not pour all their energies and attention into every assignment. The most frequent question asked when assignments are posted is, “Is this for a grade?” Our best teachers coax every bit of effort from our students when the stakes are high, such as graded tests, and certainly the spring SOL tests.

Teachers have a vested interest in their students doing their best on the SOL tests. All teachers are held accountable for the skills that they are expected to bestow on their students, and the SOL tests are used by some as a measure of that. If our students do not perform to the state’s expectation, school districts will receive visitors from Richmond who come to “help” us by making us complete enough extra work to make us wish not to repeat those results in the future. Moreover, many communities hold their schools accountable for results, and nobody wants to see their school on page one of the local paper for failing to meet full accreditation status.

What incentives are there to ensure we collect reliable data in the fall through-year assessments? In the fall we’re testing material that we have not yet taught the students, so there’s no expectation that the students will know any of it. By the winter test, we would have taught about half of the skills. Students know the test will not count as a grade. In fact, most educators realize that the better the students do in the fall, the less growth they can display in the spring. Also, we’re administering this test at a time when teachers are trying to make up for time lost to COVID, and many see this test as taking up valuable time that could be better used teaching. The incentive in place is to hurry up and get it done so we can get back to teaching school.

Negative Unintended Consequences

Negative unintended consequences have accompanied the new through-year “growth” measure. Some consequences can be mitigated and some cannot.

First, we’re squandering valuable instructional time to extract unreliable data that we don’t use for instructional purposes. This year, our 8th graders will sit for ten state-mandated testing sessions (that’s over 5% of the school year!). Prior to the through-year growth assessments, that figure would have been five — Math, Reading, Writing (two days), and Science. This year we’re adding a fall and winter assessment in reading and math, as well as a field test for a new written response item type in reading. The least-affected grades are 3rd, 6th, and 7th, which are going from two days of testing to six.

Second, everyone realizes that it is easier to help a student demonstrate “growth” in this new measure than proficiency. Everyone realizes that in the school accreditation calculation, a growth counts precisely the same as a proficient score. Given that the COVID pandemic has significantly lowered educator expectations, we’re not collectively striving as hard to ensure our students are as successful as they can be. Anecdotally, the schools in which I heard folks place more of their eggs in the “growth” basket tended to realize greater declines in student proficiency between 2019 and 2022. On the other hand, schools that paid no attention to the “growth” statistic tended to suffer smaller declines in scores.

Third is the fact that the new through-year “growth” system doesn’t guarantee that a student will eventually demonstrate proficiency if the student demonstrates “growth” each year. The previous growth model assured proficiency with continued growth.

Fourth, the new through-year “growth” system masks schools that are not meeting expectations. True, many schools have been involved with the Office of School Improvement at VDOE for many years, and identifying those schools as failing to meet accreditation standards doesn’t seem to have helped their students. However, if we continue to allow the system to whitewash sub par performance, how can that help anyone?

Recommendation

I wholeheartedly recommend that the General Assembly revisit this issue when legislators reconvene in January and conduct a serious debate about the benefits and detriments of the through-year “growth” model they voted into law a little over a year ago.

I have yet to unearth any benefits from the change. In my opinion, reversing returning to the former year-to-year growth measure would better serve our students.

Should the General Assembly decide not to act on this matter, I would favor the Virginia Department of Education recommending guidelines to mitigate the loss of instructional time. We could administer the fall and winter reading tests at 9:00, and the math tests at 9:30 of the same day without degrading the reliability of the tests.

Similarly, the law requires the “growth” statistic to be used in the calculation of accreditation ratings. However, the law does not specify to what degree. The Board of Education could adopt a new calculation methodology which credits a student showing growth as some fraction of a pass. That would offset the incentive in place to be complacent with growth rather than striving for proficiency.

Conclusion

Nothing in this essay is intended to suggest that no real student growth occurred in 2022. To the contrary, many students who failed their SOL test realized significant growth over the year. However, the current through-year growth statistic has proven to be an unreliable measure of that growth. Given the arguments presented here, our students would likely benefit a return to the previous year-to-year growth methodology.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.