Everywhere counterproductive to competition, innovation and cost, Virginia’s Certificate of Public Need (COPN) program also has proven antithetical to quality and safety in nursing homes.

A thorough 2022 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on improving nursing home quality had this to say about state Certificate of Need (CON) programs:

Certificate-of-need regulations and construction moratoria do not appear to have had their intended effect of holding down Medicaid nursing home spending; rather, these laws can discourage innovation and decrease access.

Certificate-of-need regulations may contribute to the perpetuation of larger nursing homes.

Despite the prominent role of nursing home oversight and regulation, the evidence base for its effectiveness in ensuring a minimum standard of quality is relatively modest.

The role of Virginia’s COPN program is as counterproductive to nursing home quality as is imaginable. Remember, COPN decisions happen before the state and federal regulators of the operations of nursing homes even get into the game.

Virginia’s COPN program is a statutory incumbent protection regime across all of its regulated targets. But it has gotten especially bad results with nursing homes, which by nearly every measure are among the worst in America.

In Virginia, the only realistic way to increase the size of a nursing facility is by COPN approval of the transfer of beds from one facility to another, often from one region of the state to another.

Yet we know from government data that nursing facilities as a group in this state are dangerously understaffed and that the entire state suffers from severe nursing shortages, so expansions risk further understaffing.

Transferring beds from one region of the state to another does nothing to ensure that nurses will be available in the new location. So, the COPN process is supposed to ensure that outcome.

Yet we see recent COPN approval of a more than doubling of beds in a facility that was already significantly understaffed before the proposed expansion with no indication of the source of the larger staff.

The nursing home business in Virginia. If you want to play under Virginia’s nursing home laws, you have to buy an existing facility. COPN won’t let you build a new one. To play successfully, you need to buy a group of them.

But the nursing home business is very profitable in Virginia, especially if you don’t mind cutting staff below what is necessary to care for patients. Which is a sin that is routinely forgiven in this state.

Which is why our nursing homes are so bad on the whole.

I have written before that nursing home ownership by private investors is at its core a real estate play.

The real estate values of nursing facilities in the Commonwealth are secured by state-guaranteed artificial scarcity. It ensures that no new ones are ever built — except by incumbents replacing their existing facilities.

Very sweet deal if you are an owner.

Your investment in land and facilities is reflected in capital costs, which in turn drive up government reimbursements by the government’s own formulas.

When operating companies pay rent, the investors get that cash flow before profits are counted. And then they distribute the profits. When all of that together increases, so does the value of the real estate. That is called a virtuous cycle by the owners.

Investors seek 20% annual profits net, and many get them.

Virginia’s nursing home bed transfer law. The state law governing COPN approval of the transfer of nursing home beds from one place to another has lots of hoops to jump through to get approval.

Some of which are even nominally in the public interest — like sufficient staffing. But those that are have regularly been avoided for many years.

Bad enforcement. Consider the recent case in which one of Virginia’s relatively few non-profit nursing homes, Our Lady Of Peace (OLOP) in Charlottesville, requested to expand its authorized capacity from 30 beds to 64. It proposed to use surplus (as calculated by COPN) beds from Southwestern Virginia to accomplish the expansion.

§ 32.1-102.3, B. 6. of the Code of Virginia requires consideration of:

the feasibility of the proposed project, including the financial benefits of the proposed project to the applicant, the cost of construction, the availability of financial and human resources, and the cost of capital; [Emphasis added.]

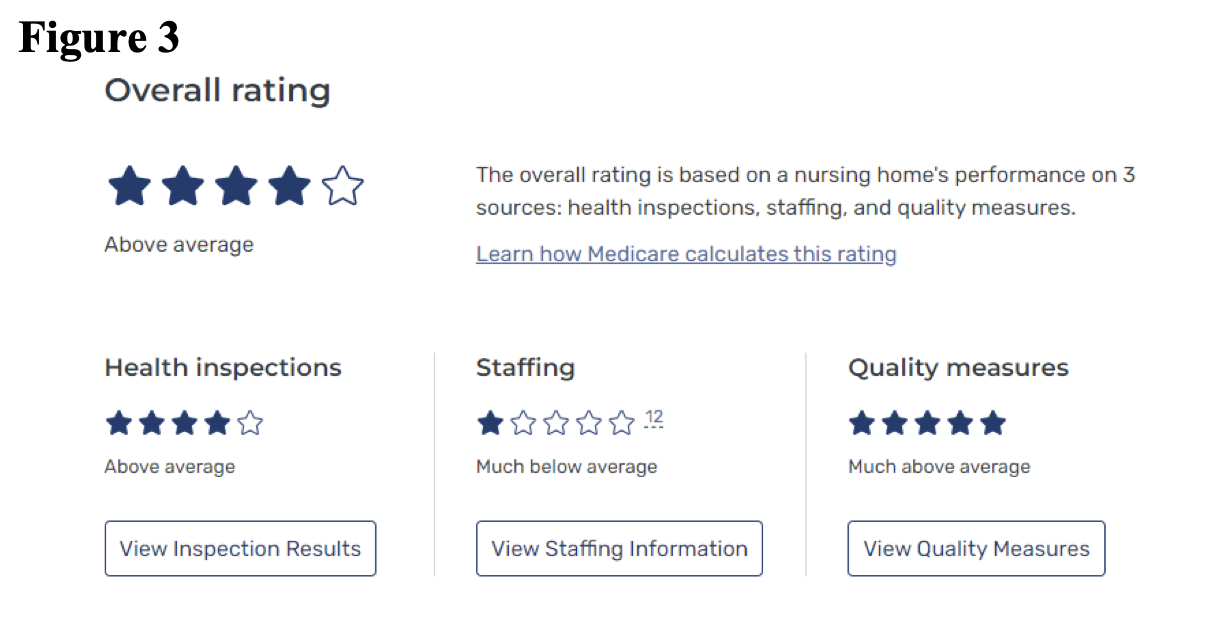

OLOP, at the time the expansion request was reviewed, had a CMS rating of one-star staffing in its existing facility.

Here is how the DCOPN staff in their March 21 Staff Analysis blew off the “availability of human resources” requirement in a state with a massive shortage of nurses:

DCOPN notes that OLOP was given a CMS Star Rating of 1 for staffing.

Details from the Medicare.gov website indicate that this rating is likely due to higher utilization of nurse aides and lower utilization of registered nurses than national and state averages. [Author’s note: If true, that would mean registered nurses were not available in sufficient numbers to supervise care and to tend to patients whose level of care required nurses with their licenses.]

OLOP also has lower turnover, 41.4% (a very positive staffing indicator) than both the Virginia and national averages (56.% and 53.9%, respectively). [Author’s note, the turnover rates were considered by CMS when the staffing rating was assigned to OLOP.]

This information may suggest that OLOP will have challenges staffing the additional 34 beds; however, the applicant has a 5-Star Quality rating and 4 Stars for its overall rating with current staffing, as well as letters of support documenting caring, dedicated staff and excellent care.

In short, the DOCPN staff noted an existing nursing shortfall at OLOP. The rationalization used to get through that hoop does not withstand even cursory examination. Even as it entirely ignored the severe shortage of nurses in Virginia.

The Acting Health Commissioner, Dr. Jaberi, approved the request on April 11. His first statement in his approval letter was:

The proposed project is consistent with the 8 required Considerations of the Code of Virginia.

Except that it clearly is not.

Good enforcement. The new Health Commissioner, Dr. Karen Shelton, M.D., indicated in her first decision on nursing home bed shifting that there is a new sheriff in town.

She turned down the first application presented to her, noting the substantial cost of the project would put “additional upward pressure on systemic healthcare costs.” That is because as nursing home costs go up, so does the output of the formula that determines Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

She refreshingly added:

While the project would be of economic benefit to the applicant and the private equity owner that recently acquired this nursing home, it would be of no substantiated public value or benefit.

Bottom line.

The National Academies report was right. CON programs are counterproductive to cost, availability, competition, innovation and quality in the nursing home industry. Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln….

Virginia continues to have COPN regardless of the negative impacts to public interests pointed out by the National Academies.

That is because the General Assembly and our Governors have been subservient to the political and financial power of the hospital and nursing home industries. Some of that is local politics. Some is Virginia’s limitless campaign contributions.

But COPN is now administered by a commissioner who at least considers the public interest within statutory limits. Good for her.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.