by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon

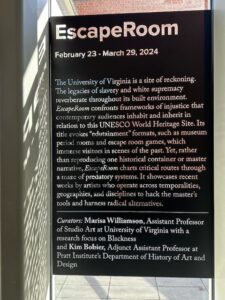

If you visit the latest exhibit at the University of Virginia’s Ruffin Gallery, “EscapeRoom,” it takes no more than five or ten seconds for the artists’ message to sink in — the amount of time it takes to read the signage at the entrance:

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a site of reckoning. The legacies of slavery and white supremacy reverberate throughout its built environment. EscapeRoom confronts the frameworks of injustice that contemporary audiences inhabit and inherit in relation to this UNESCO World Heritage Site. … EscapeRoom charts critical routes through a maze of predatory systems.

Inside, the exhibits contributed by multiple artists elaborate upon the white-supremacy theme. Five 3D-printed pieces of porcelain, for instance, are described as giving “materiality, scale and dimension to the many ‘tools’ that mediate state violence visited upon Black victims: horses, batons, guns, tear gas, and more.”

A mobile made of steel sheet metal “examines violence visited upon Black people at the hands of the American state. It attends to the paradoxes of Black life and death in this anti-Black world.”

To set foot in the EscapeRoom is to enter a world of victimhood that would have been entirely justified a century or two ago but seems tragically out of date 60 years after the passage of Civil Rights legislation, the enactment of the Great Society’s war on poverty, and the dramatic transformation of attitudes toward race in America — not to mention the implementation of Racial Equity Task Force recommendations at UVA itself that made the exhibit possible in the first place.

Back in 2020 I was saddened and appalled when a student living on the Lawn scrawled “F— UVA” in massive letters on her door. In a subsequent TV interview she referred to the Lawn as a “space for whiteness” and Thomas Jefferson as a “white supremacist rapist and enslaver.” Where did this animosity originate, many of us wondered. How had such thinking gained legitimacy at Mr. Jefferson’s university?

The EscapeRoom exhibit provides part of the answer. The curators and artists speak not only for themselves. They speak with the approval and support of a University administration that has made a point of not just hiring more minority faculty and staff to the University but recruiting minorities marinated in the ideology of intersectional oppression.

It is entirely legitimate to research and reflect upon the impact of slavery and racism in America, Virginia, and UVA. That is part of our history, and it must be incorporated into our collective memory. But what we see from University leadership under the guise of being “great and good” is an unremitting fixation on injustice, grievance, and victimhood that (1) drives home the message that racism and injustice are endemic are still prevalent today; (2) offers no vision of a way forward other than criticizing “whiteness”; and (3) solicits no alternative perspectives.

Not every scholar at UVA subscribes to those propositions. Many faculty members whose hiring preceded the current administration entertain more diverse perspectives. But faculty recruitment under President Jim Ryan has heavily favored faculty who do share the intersectional-oppression paradigm. In recent years, UVA has pulled every financial leverage available to advance the woke narrative. The $20 million spent to maintain UVA’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion bureaucracy identified by Open the Books only scratches the surface. Intersectional-oppression rhetoric pervades every part of the university.

The EscapeRoom exhibit is illustrative. The Ruffin Gallery, located just off Rugby Road, showcases four to six contemporary art exhibits yearly. Those exhibits receive financial support from a variety of sources. EscapeRoom, for instance, is sponsored by three entities: the UVA Arts Council, the Vice Provost for the Arts, and the Department of Art.

The lead curator of the art exhibition is Marisa Williamson, an assistant professor of studio art. For a deep dive into her worldview, see the profile we are publishing in conjunction with this article, but in brief, she describes herself as a project-based artist who works in video, image-making, installation and performance “around themes of history, race, feminism, and technology.” At various times, she has engaged in performance art as Sally Hemings, alleged rape victim of Thomas Jefferson, and has portrayed Jefferson’s ghost in whiteface.

Despite her status as a victim of intersectional oppression (doubly held down as Black and as a woman), Williamson nonetheless managed to get admitted into and graduate from Harvard and go on to win grants from the Graham Foundation, Rema Hort Mann Foundation and the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. In 2018, she was appointed the Ruffin Distinguished Artist in Residence at UVA. Her works have been featured in exhibitions around the country and abroad.

According to her UVA website, Williamson was part of the first cohort of faculty hired through a $5 million initiative devoted to “Race, Justice and Equity.” That builds upon a $3.5 million Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-funded grant to hire 10 tenure/tenure track faculty working on the Global South (Africa, Latin America, South Asia, East Asia, and other regions); another Mellon Foundation grant to appoint “30 Race, Place and Equity” postdoctoral fellows across the University; and a University endowment commitment to recruit “underrepresented graduate students.”

“Our national reckoning on race, justice and equity will test and sharpen our commitment to democracy and reshape the nation: comprehensively, and one community at a time,” stated the November 2020 proposal to Mellon submitted by Provost Ian Baucom, DEI head Kevin McDonald, and the deans of the Batten school of leadership, the McIntire school of commerce, and the College of Arts & Sciences.

One of the best means by which we tell that history is through place-based education and by bringing a next generation of scholars to this place, a University that lives at that point of urgent intersection, to help us imagine and shape its future. [My bold.]

The proposal suggested that “a robust racial equity post-doctoral fellows and faculty-hiring program … will build a community of scholars of race, justice, and equity who can help lead our university, our community, and the nation.”

The exhibit itself was sponsored by the UVA Department of Art and the UVA Arts Council. In the 2022-23 year, the Arts Council disseminated $127,000 in grants to Charlottesville-area programs, including $10,000 to Ruffin Gallery “exhibitions and artists in residence.”

The abstract multimedia presentations might bewilder some visitors to EscapeRoom. In an interview with WTJU radio, Williamson provides an explanation that might prove helpful to those who find the artwork an unintelligible jumble of words, images and themes. “One big theme is race, vision and surveillance,” she said. “That might give us some clues into how Black and brown, and women, and fem people who are vulnerable in society might combat or avoid these dominant surveillance strategies.”

“I wanted to lay a groundwork for being able to interrogate the university from within and perform some institutional critique in a subtle way to get those conversations started about what can be done, mapping the history of this university so we can start repairing where we can in very specific ways,” she continued.

“This show,” she said, “is just the beginning of a larger effort to make visible a hidden past here at UVA.”

James A. Bacon is executive director of the Jefferson Council. This article was published originally on the Jefferson Council blog.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.