Carlos Ortiz underwent tests last year at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg for dizziness stemming from an inner-ear problem. When the 65-year-old uninsured gardener couldn’t pay his $15,000 bill, the nonprofit institution took him to court. Mary Washington was suing so many patients that day that the circuit court had cleared the docket to hear all the cases.

As it turns out nonprofit hospitals are more likely than for-profit hospitals to garnish patients’ wages to collect their bills, according to a study of Virginia hospitals published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association and reported upon by the Wall Street Journal. In 2017 Virginia nonprofits filed 20,000 lawsuits against patients for unpaid debt.

Remarkably, the study found, nonprofits are more likely than for-profits to file lawsuits against patients for unpaid debt. These numbers do raise fundamental questions about Virginia’s social compact with its nonprofit hospitals. But hasty judgments are not in order.

The Affordable Care Act, which created subsidized insurance offerings and expanded Medicaid, was enacted with the expectation that it would relieve hospitals of much of their social burden in the form of charity care and unpaid bills. But if the aggressive pursuit of unpaid bills for people like Carlos Diaz are any indication, little has changed.

Mary Washington patients receive a 30% across-the-board discount, a Mary Washington Hospital spokesperson told the Journal. Plus, the hospital provides millions of dollars in uncompensated care. “We go to court because we want to get patients to engage with us,” she said. “We do have to pay our bills as a nonprofit.”

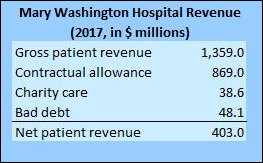

The Virginia Health Information website provides data that puts Mary Washington’s bill collection efforts in context.

In 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, Mary Washington reported the following:

“Gross patient revenue” is a totally fictitious revenue number (as it is with all Virginia hospitals). It reflects hospital charges before any “contractual allowances” — discounts negotiated by private health insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid — are applied. We can see from these numbers that, collectively speaking, insurers get a 64% discount on billings. The insanity (actually, one of many insanities) of the our health care system operates is that hospitals are incentivized to boost their charges in a way that bears no connection whatsoever to the cost of actually providing the services as apart of their ongoing negotiations with insurers.

The big losers in this process are the uninsured, who have no bargaining power to negotiate discounts on their bill. Although Mary Washington may provide a 30% across-the-board discount, that’s only half of what Medicare, Medicaid and private insurers collectively get. (As a generality, Medicaid gets the biggest discount, private insurers the least.)

Mary Washington does provide $38.6 million in charity care and it does write off $48.1 million in bad debts: a total of $86.1 million in uncompensated care. If I understand these numbers correctly, these numbers do not reflect costs incurred, they reflect hospital charges. Even assuming that a 30% discount was applied, the charges are probably inflated 30% to 40% over actual costs. A realistic number for actual costs incurred for uncompensated care would be in the $50 million range.

How does that compare to profitability? Mary Washington profits (“operating income”) amounted to $14.5 million, a profit margin of about 3.5% of revenue. That is not an inordinate number. Even nonprofits need to generate an operating profit in order to reinvest in their core business enterprises. And the sum is a drop in the bucket compared to the “nonprofit” VCU Health System, which generated FY 2017 profits of $237.4 million, a profit margin of 15.1%.

As compensation for its uncompensated care, Mary Washington Hospital pays no taxes. How much is that status worth? Hard to say. For an order-of-magnitude idea, let’s look at CJW Medical Center, a major for-profit provider in the Richmond region. CJW paid $56.4 million in taxes in 2017, comprising 8.9% of its total expenses. An equivalent tax-to-expense ratio for Mary Washington would be $36 million. Without the tax break, one could argue, Mary Washington might have lost money.

As a hospital with a thin profit margin, Mary Washington can make a defensible case that it needs to both maintain its nonprofit status and collect unpaid bills in order to maintain its profitability, which in turn is necessary to meet the needs of a growing Fredericksburg-area population. Meanwhile, some nonprofit hospitals, especially in rural areas, are losing money, while others, mostly in metropolitan areas, are phenomenally profitable. The question of whether nonprofit status and aggressive bill collections are warranted needs to be made on a case-by-case basis.

It will be interesting to see if Medicaid expansion has any effect on Mary Washington Hospital’s numbers. Unfortunately, due to delays in reporting financial data, we won’t know for another couple of years.

Update: In the aftermath of the American Medical Association report, Mary Washington Healthcare has suspended the practice of aggressive collecting unpaid bills. The nonprofit says it will review its collection processes from top to bottom, reports the Free Lance-Star.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.