Poor Jaqueline Siegel. She’s another victim of the credit crunch. Her steel- and wood-frame Florida home remains unfinished. As she stands on the deck of her Florida room, she wipes away tears as she speaks to a Wall Street Journal writer. “Maybe it will still work out,” she says. “It always does, right?”

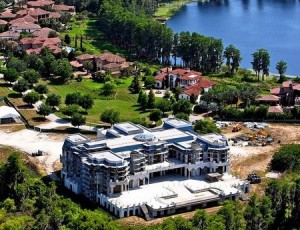

It’s not a sob story that many Americans can relate to. Ms. Siegel’s dream house is a monument to conspicuous consumption: 90,000 square feet (believed to be the largest private home in the United States), a 7,200-square-foot ballroom, a bowling alley, five kitchens, 23 bathrooms, 13 bedrooms, two elevators, two movie theaters, a 20-car garage and artificial, 80-foot waterfall. When her husband’s business, Westgate Resorts, got slammed by the recession, the couple had to pay off about $1 billion in notes they had personally guaranteed. The house had to go. It’s now on the market for $75 million.

Jacqueline and David Siegel belong to what writer Robert Frank calls the “High-Beta Rich,” a comparison to high-beta stocks that rise and fall in value with great volatility. The new mega-rich, who often engage in conspicuous consumption, are often only one crisis away from financial ruin, Frank observes. The Siegels managed to downsize quickly enough to stay solvent, but they had to lay off 14 of their 15 housekeepers and their chef, and enroll their children in public school. Waaah!

But many like them go belly up. Americans who live atop the economic ziggurat today are not a stable group. As Frank writes:

Though often described as a permanent plutocracy, this elite actually moves through a revolving door of riches, with some of today’s nouveau riche becoming tomorrow’s fallen kings. Only 27% of America’s 400 top earners have made the list more than one year since 1994, one study shows.

It wasn’t always this way. For decades after World War II, the top one-percenters were the most steady line on the income and wealth charts. They gained less during good times and lost less during contractions than the rest of America. Suddenly, in 1982, the wealthiest broke away from the rest of the economy and formed their own virtual country. Their incomes began soaring higher during good times. The top 1% of earners more than doubled their share of national income, to 20% as of 2008. Looking at another measure, the richest 1% increased their share of wealth from just over 20% to more than 33%.

Those surges were often accompanied by mini-crashes, even though the direction over time was always up. A top 1% that had once been models of financial sobriety set off on a wild ride of economic binges.

As Frank rightly observes, this new class of high-beta rich doesn’t conform nicely to ideological stereotypes. It certainly doesn’t fit the conservative stereotype of vast wealth as the reward for years of hard work and thrift. Many of America’s great fortunes are fueled by huge indebtedness and good luck, not real wealth creation (think Donald Trump). Nor does it fit the liberal notion that America is dominated by a new “ruling class” or plutocracy. One year people are rich, next year they’re not.

As we think about using tax policy to get “millionaires and billionaires” pay their “fair share,” it’s useful to remember that only one quarter or so of the taxpayers in the top 1% remain there year after year. For most Americans who break into that illustrious club, it’s a temporary stay. American society is still very, very fluid.