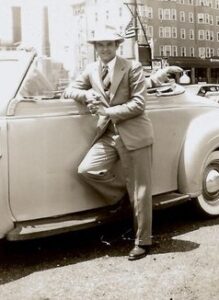

I wrote this column in June of 1998, just weeks after my father’s sudden death of a heart attack. (He died riding his exercise bike at age 74.) In many ways, this post is dated. Yet I hope it still is meaningful. I loved the guy.

To make sense of the piece it’s worth noting that on May 7, 1998 — the day Dad died — the Dow Jones Industrial Average was 8,976. Morrison’s Cafeteria in Virginia Beach closed many years ago. The round-trip toll on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is now $36, not $20. Worse, they no longer give you a coupon for a free thimble full of Coke. I guarantee you that would have ticked off my father.

This is the first year in my life that I have no one to call or send a card to on Father’s Day. My dad died six weeks ago.

Then again, the card thing always posed a problem, as Hallmark never produced one that captured the spirit of my father. He was a child of the Depression, a character out of a Jimmy Stewart movie. He was a cross between Bishop Fulton J. Sheen and Norman Vincent Peale. He was a man who had eaten in some of the finest restaurants in America but preferred dinner with his grandchildren at Morrison’s Cafeteria.

Wherever he ate, he always said grace first.

Dad was generous to a fault with his family and friends, but pinched pennies in unlikely places. He cheerfully paid his taxes, lavished gifts on all of us, donated heavily to charity, but hated toll roads.

He liked playing the stock market and was positive it was heading for 10,000. He dreamed of someday owning a horse. He was totally color blind and his socks never matched. He was the pitching ace — a southpaw — on his high school baseball team, but the World War II ended his dreams of playing in the Big Leagues.

He once quit his job and joined a carnival. He loved New Jersey.

Where do you find a card for a man like that?

I used to pore over the racks of Father’s Day cards trying to find just the right one. Every once in a while, for fun, I’d send him one of those preppy golf cards. My dad played golf just once. I suspect he lost a $1.25 ball in the woods and that was enough for him.

My dad’s idea of a great day off was working as a volunteer at an old folks’ home, writing letters, walking his dogs or composing poetry. He also liked to attend shareholder’s meetings of companies whose stock he owned. There, he’d publicly — and relentlessly – -needle CEOs about their inferior products or poor customer service.

He once hounded the chairman of Sears so severely over a Craftsman mower that wouldn’t start on the first crack that the company sent him a free one.

When my investment club bought Oxford Health Care stock my father disapproved. “People hate their health insurance companies. I never buy stock in things people hate. Invest in things people like.”

Merrill Lynch had nothing on my father. The stock crashed, never to recover. If only I’d listened.

For years we tried to get my parents to move to Virginia Beach to be closer to their grandchildren and to spare all of us frequent 12-hour car rides.

Mom was tempted, but not Dad. One day, as we were driving around the Beach, he remarked on the trend toward colorful banners hanging at each doorway.

”This is the kind of place where people would rather fly a pineapple than the Stars and Stripes,” he observed. I knew then he’d never leave the gritty confines of Trenton, N.J.

Just hours after my father died my family and a group of friends were sitting around the old kitchen table, drinking, crying and laughing.

We all had tales about his love of bargain gasoline and his disdain for tolls. He’d drive miles out of his way to save a few pennies on gas or to avoid a toll booth. When tolls were inevitable, he was not above looking around on the ground for spare change.

It was a game with him.

My brother remembered traveling from Washington, D.C., to New Jersey with my father a few years ago. Dad suddenly veered off an exit shortly after the Maryland House Restaurant in order to miss the JFK Highway toll.

For the next hour they bounced along rutted country roads and through downtown Elkton, Md., in Dad’s Oldsmobile before triumphantly rejoining the free section of I-95 near Wilmington. He was the Che Guevara of the interstates.

Imagine, then, my father’s chagrin when long-awaited grandchildren were born and the price to see them was a $20 round-trip toll on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. His devotion to the kids was such that he never complained about the long drive or the steep tolls.

But he always redeemed his coupon for a free Coke at the Seagull Pier.

Once, when he was coming by himself, my dad detoured through Annapolis and down the Northern Neck. He arrived at our house, bedraggled, nine hours after he’d left home. “It was a beautiful ride,” he declared, refusing to admit it was part of a toll-avoidance scam. “Your mother would love it.”

As I said, it was impossible to find the right card for that man.

Last weekend, on a return trip from New Jersey, I did something I’d never done before. I stopped at the Pier and had a free Coke.

Looking out over the Bay, I silently toasted the guy who had always been so hard to buy a card for. Toll collectors rarely made a dime off him, but I was always rich when he was around.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.